It seems that everyday, companies are promising us one thing: life is going to be amazing in the “world of tomorrow.” That was the main promise that the US government gave Americans during World War II, as well, but when the war ended many companies, along with the US government, turned back on that promise as quickly as they could.

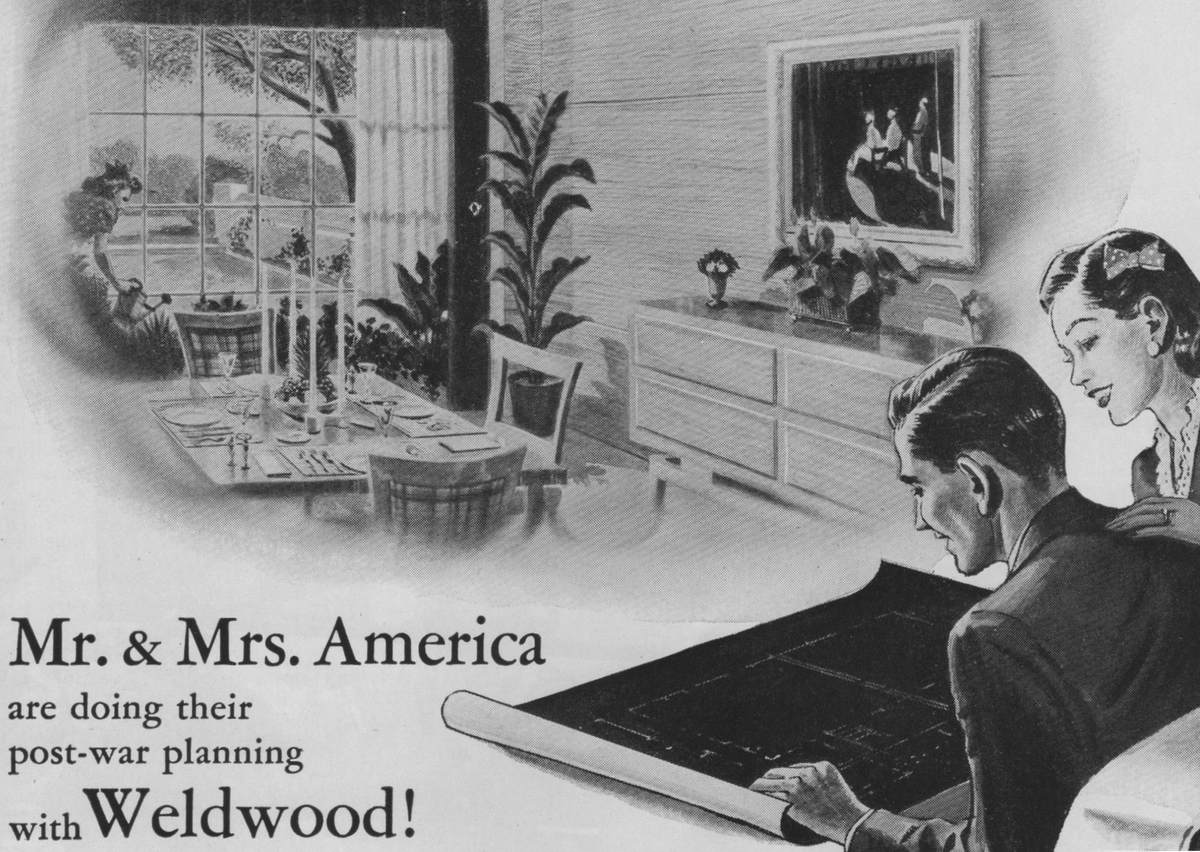

Americans were told that as soon as the war was over, everyone would have so many shiny appliances and bubble-top cars and super-modern homes that they wouldn’t even know what to do with them all. Sure, you may have to sacrifice now, with the wartime rationing of everything from gasoline to sugar, but once victory has been achieved the good life is ahead.

The house of tomorrow — the miracle, push-button, prefabricated house of the future — was on its way even before WWII began. These promises were a hold-over of pent up desires left simmering and unfulfilled during the Great Depression of the 1930s. The legendary World’s Fairs of 1933 in Chicago and 1939 in New York gave Americans a look at the house of the future, and after years of toil and sacrifice, luxury was surely coming soon. Or so they were told.

As Americans became more and more confident of victory in WWII during the war’s later years of 1944 and 1945, cracks started to appear. People started to write articles (often unsigned or pseudonymously) in newspapers and magazines telling Americans to keep their shirts on.

That house we promised — that assurance that everything will be amazing after the war is done and peace has been secured? Now don’t get your hopes up, Mr. Futurepants.

According to a fascinating 2005 paper by Timothy Mennel titled, “Miracle House Hoop-La,” this wasn’t a few sceptics who were telling Americans that they shouldn’t expect too much. It was a coordinated effort by both the U.S. government and the housing industry to make sure that Americans kept their futuristic expectations in check. This, after both the government and industry had been the promising the house of tomorrow as a sure thing for so long.

This dialling back of expectations started to pop up in newspapers and magazines across the country. From the January 3, 1944 Times Recorder in Zanesville, Ohio:

The House of Tomorrow will not be a completely prefabricated “dream home” stamped out like a cookie, according to the best authorities in the building industry.

A metal residence hung like a bird cage or a single block of weird design makes a provocative magazine picture, but the average prospective owner and architect are too conventional to accept immediately such revolutionary, futuristic contraptions.

Did you catch that? The futuristic house of tomorrow we’ve been promising might look interesting in a glossy magazine, but you don’t really want one, do you?

As Mennel explains, none of the builders wanted to be held responsible for actually delivering on any of their promises once push came to shove. Efficient prefab construction would be anything but a miracle, according to people with a vested interest in maintaining old fashioned building techniques:

Paddy Sullivan, president of the Building Trades Council of Chicago, called on other industrial leaders to “have the courage to condemn innovations toward ‘miracle housing’ that will produce the slums of tomorrow.”

Trade organisations and builders of all stripes joined in the call for a tamping down of public expectations — especially those that might get cut out of the new modern style of construction. You see, plastic and glass and steel were the future. And since wood wasn’t exactly presented as the building material of tomorrow, organisations like the Arkansas Soft Pine Bureau were happy to contribute by advising the industry to tone it down with articles like “Take It Easy, Builders, About Miracle House Hoop-La.”

Mennel sees this coordinated effort by industry as a way to associate the house of the future with a certain kind of foolishness:

Clearly the trope of the miracle house was being forcibly associated with waste and failure, in order to protect the status quo and absolve corporations from the responsibility of bringing expensive visions into existence.

The U.S. government acknowledged the effort to kill the miracle house of tomorrow in a 1945 report from the Bureau of labour Statistics. If nothing else, the inevitable failure to deliver on over-the-top promises during the war would more or less fix itself:

An active effort to correct these impressions has been started through advertisements… It will be reinforced strongly by the postwar houses themselves which will be their own demonstration that the numerous irresponsible promises… cannot be met at present.

The labour Department also issued a 1945 report analysing the some 1400 new technological developments that had grown up during the war. The high cost of building materials of the future (one word: plastics!) were singled out with language to makes sure consumers remained level-headed: “The future of the plastics industry will be governed largely by economic factors,” the report explained. “The price per pound of most plastics remains higher than that of many materials with which plastics compete.”

The January 1945 issue of Architectural Forum applauded the, “understandable and sensible campaign of counter-propaganda leveled against the terrifying prospect of a market nourished during lean war years with gilt-edged, but worthless promises.”

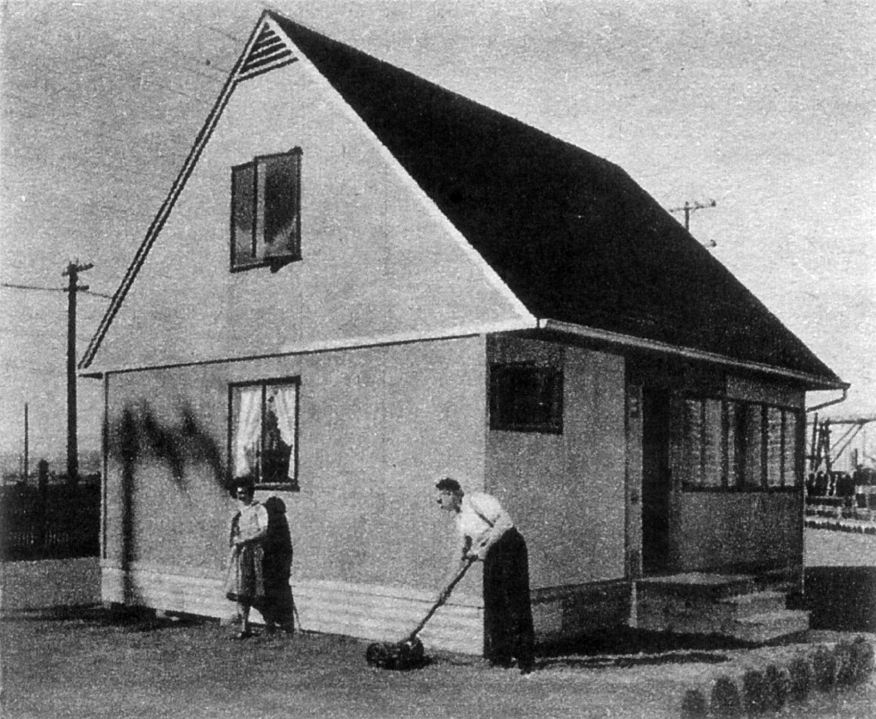

What many Americans got after WWII was far from the miracle house of the future. There was nothing wrong with the “workingman’s house” for those soldiers returning from war, but they didn’t even come close to the promises being made just a few years earlier. Expectations were managed and modesty was in vogue. What constituted a house that was “futuristic” were developments that already existed before the war.

This modesty, as Mennel contends, was made to look like the only obvious and rational choice for red-blooded Americans in the mid-1940s. You don’t want to be irrational, do you? All those futuristic advancements we promised were just a bit of puffery. Be reasonable, they insisted.

The broad success of such claims relied on convincing individuals that their spatial pursuit of happiness was in fact not part of a larger program of industrial organisation and domination but merely an expression of their own communally grounded, rational, and socially validated needs and wants.

We may have promised you the miracle house of tomorrow, but we know what you really want.

The push-and-pull between companies that promised the moon, and organisations that wanted to deliver something more like a slideshow presentation of the moon, didn’t stop in 1945. In fact, the most techno-utopian promises of the 20th century would arrive in the following decade once America had bounced back from its postwar recession.

But while people of the 21st century might lament their lack of whatever they were promised — a flying car or jetpack or hoverboard or a living wage — yours is not the first generation to be betrayed by promises of the future.

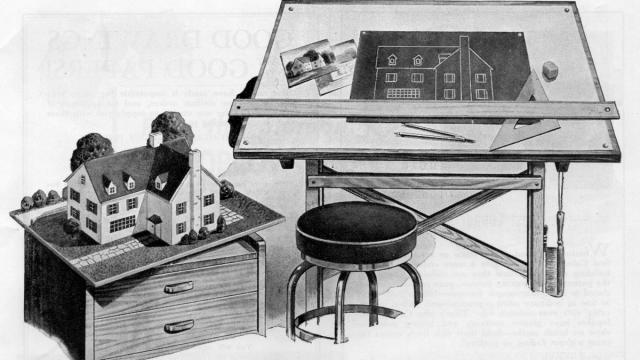

First two images: November 1944 issue of Pencil Points magazine, Bottom image: postwar Home-Ola brand house via Timothy Mennel’s 2005 paper, “Miracle House Hoop-La”