I tried a little experiment the other day — and I’m not sure why I hadn’t tried it before. Before I walked to the bus stop to go into the city, I checked the real-time arrivals for my stop. It turned out the bus wasn’t coming for another 11 minutes, so I did the dishes first and only then left the house. The bus arrived when it said it would, and I was on my way.

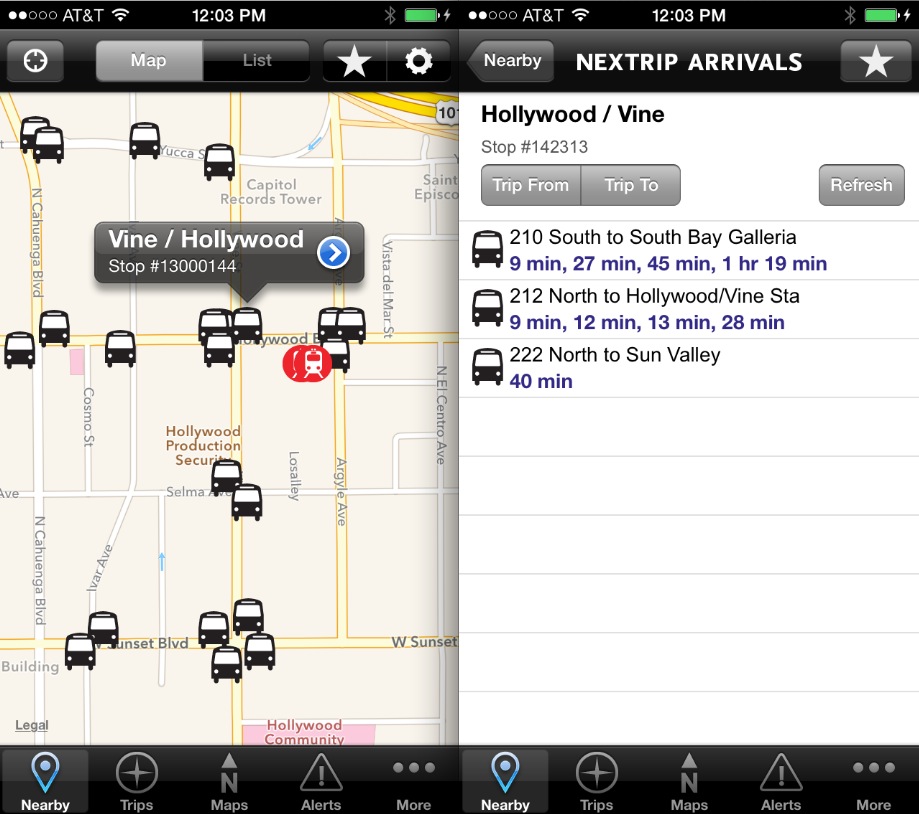

It might not sound like an earth-shattering experiment. These real-time arrival apps have been around for a while (I use LA’s Metro app, which uses NexTrip tech, but there are likely plenty of options if you live in a city with a fairly robust transit system), and we use them at our bus stops or from our kitchens or maybe in a bar, where we can figure out that we do, indeed, have time for another drink. But what I think is pretty amazing here is that, technically, I never had to wait — or at least I never had to experience the traditional sense of waiting.

As we are able to gather and use more real-time transit information, this data will have massive implications for the way that people embrace transit — especially the people who are trying the bus for the first time. For those who aren’t used to riding transit, the Great Unknown Wait can be the hardest part. Especially if you’re at dark bus stop in an unfamiliar part of town. In the rain. With groceries.

You know the feeling when you’re waiting for a bus. It takes FOREVER. But it turns out it’s largely perception. In a story over at Atlantic Cities, Emily Badger looks at a study by two University of Washington students, Keri Watkins and Brian Ferris. They timed how long transit riders waited at bus stops, then asked them how long they thought they’d been waiting. Bus riders on average estimated their wait was 50 per cent longer than it actually was. Watkins and Ferris decided to see what would happen if they gave their bus riders more information, so they developed a real-time arrival app named OneBusAway to test their theory:

Its first users were in the Seattle area, and Watkins and Ferris found in their visits that people who relied on the app were much more accurate in estimating how long they had to wait for the bus. For them, perceived time and actual time were one and the same… Riders who used OneBusAway not only perceived that their waits were shorter, they actually waited for less time, too, because the app enabled them to plan their travel better. Why head out for the bus right now, if you know it won’t come for another seven minutes?

It was exactly what I had experienced. It turns out when you have the data right there in your hand, you can plan the next 11 minutes of your life. Your public transit journey suddenly becomes agony-free. Your life is enhanced.

There are some issues with real-time arrivals. Short of installing every bus stop with a screen, real-time arrivals require people to use smartphones (although the bus stops in L.A. have signage that instructs riders how to get a real-time update with a simple text). And, in most cities, rail lines haven’t caught up to buses when it comes to real-time arrival vibes, so you’re probably gonna slog it all the way down to the platform before you know your train is late. Of course, nothing’s worse than when the data’s wrong — which it can be — and you’re stuck waiting for a “phantom bus” that never arrives.

But it turns out that these data-related improvements — which are tiny things, really, when compared to big investments like station design — are more likely to keep transit riders happy. Back to Badger’s piece at Atlantic Cities:

In surveys of these early OneBusAway users, 92 per cent of them reported that they were more satisfied with public transit as a result of using the app. And the regional transit agency, King County Metro, didn’t have to reduce fares or invest in new buses or even increase service frequency to get it.

These studies — and others like them — prove that it might behoove transit authorities to focus first and foremost on creating these data tools before they spend money elsewhere. Instead of employing structural engineers, maybe cities should be focusing on hiring developers to figure out how to share their information with riders — and making more data public so even more people can come up with ways to make riding transit feel good.

Of course, not even a great app can help you feel good about waiting for a bus when you’re looking at the arrivals screen and seeing “1 hr 12 min.” But if you know it’s going to be that long, you can decide to use Uber instead. Or, as I’ve done in some cases, you can use the app to see what other buses are nearby, walk to a different stop and take a different route home.

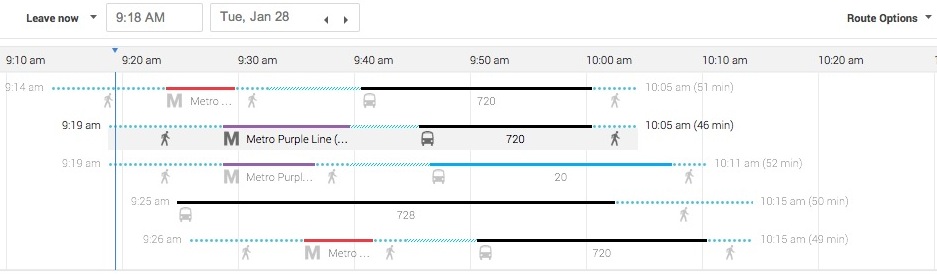

That flexibility is something we feel like we give up when we trade a car (or even a bike) for a bus or a train. Transit runs on a schedule, which we quickly inherit as our schedule, with all of its problems and delays. But then I look at something like Google Transit directions (above), which are not real-time (yet) but offer some pretty awesome evidence for the fact that more information can help us feel like we have more choices.

When directions like this are combined with real-time updates, your trip to work one day might be something more like: Leave now, get your 45 minutes of exercise in while walking to this station, then take this train that’s running a little late. The next day, the data might recommend a nearby bus knowing traffic is light. Knowing we have options is a liberating feeling when we feel like we’re bound by transit. We can do our dishes while we’re waiting for the bus.

And that’s another thing that really hit me as I was walking to the bus stop that day. The experience of “waiting” for transit — something that has plagued train, subway, and bus riders for two centuries — will not really exist anymore in a few years. But, of course, all transit will run so much more smoothly when we have self-driving cars.