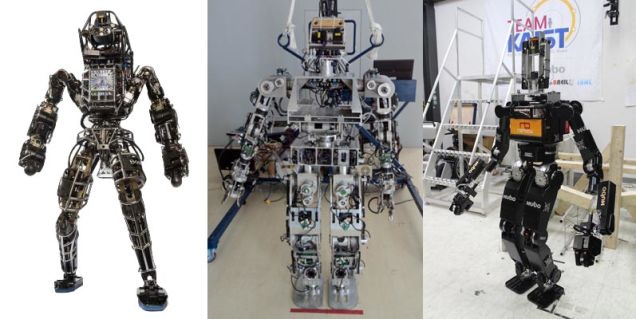

Last week, we learned the rules for the final round of DARPA’s Robotics Challenge. It was immediately apparent that we’re teetering on the precipice of a futuristic future, where robots can walk around on two legs doing work without human aid. The reality is not unlike the Space Age fantasies from 50 years ago.

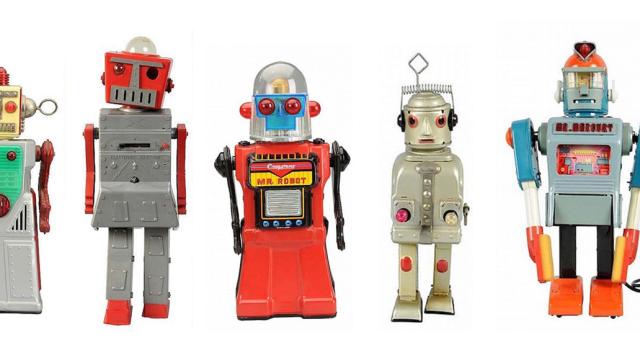

The designs themselves are more similar than you might imagine too. A recent auction of vintage toys provided a fun look into what designers of yesteryear thought humanoid robots would look like in the future. The trends are pretty apparent.

These robots adhered to very traditional boxy look with two arms and two legs.

Their torso often served as a display of sorts with loads of dials and gauges, presumably to show off now archaic metrics like oil pressure or fuel intake.

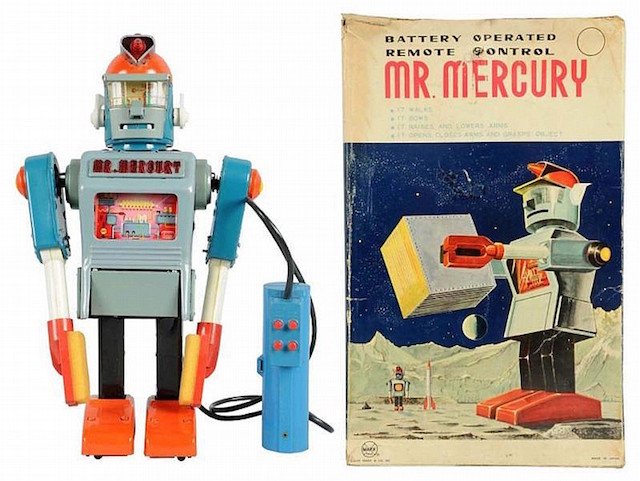

Many of the robots have approachable human names like Mr. Mercury or Mr. Patrol.

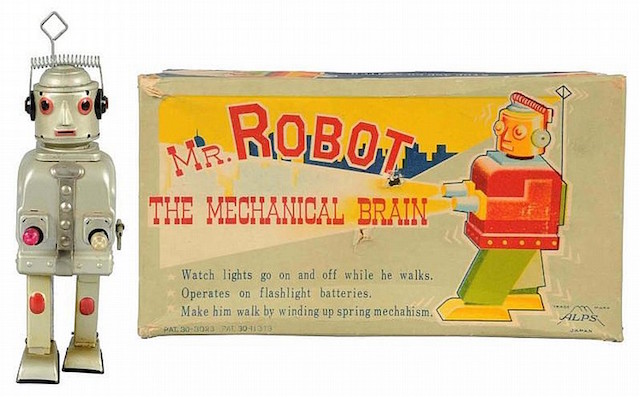

Mr. Robot was apparently a very popular name.

No, seriously, it was super popular.

Some even have human faces painted on them.

We now know that real robots don’t need so many pleasantries, but the humanoid approach did stick. For the most part, the competitors from the last stage of the robotics challenge adhered to the simple four-limbed approach, although some got a little bit creative with how the machines moved around.

Many of the robots had heads and some even had faces. And perhaps most noteworthy, DARPA’s own Atlas includes a torso-mounted display that mostly just looks cool.

Once you take a step back and think about it, the consistency makes great sense. Robots are pretty scary things to some people, in part because they have always been a hypothetical technology. Back in the 1950s and 1960s, toy designers surely gave many of them a human face, so that kids could relate to the machines and think of them as characters. Rosey from The Jetsons is another great example of how humans assumed they’d build robots in their own likeness.

Now that we’re actually building robots, it’s a little bit harder to tell why we’ve continued on the path of humanoid machines. Many robots already on the market are basically jjust boxes on wheels, which seems like a more efficient way of getting around than legs. iRobot’s Roomba and Amazon’s product-picking robots are good examples. But those robots don’t really have to interact with humans very much.

The purpose of DARPA’s robotics challenge is to build robots that could assist humans in disaster scenarios. The competing robot builders apparently assume that a more human-like design would be better. And since wheels don’t work on rubble, legs make great sense. More than anything, though, it seems like the preferred approach to robot design is the one that seems most relatable to humans. Or maybe modern robot designers like old robot toys so much they built real robots in their likeness.