Calculus: A word that triggers involuntary fear spams in the best of us. But the days of slogging through tedious textbook derivatives are over, if you want them to be. For the past few years, people across the world have studied calculus for free online, by exploring a set of gorgeous, dynamic animations.

“My goal is to make things as open and accessible as possible to learners all over the world,” maths professor Robert Ghrist of the University of Pennsylvania told Gizmodo.

At his day job, Ghrist teaches calculus to hundreds of students a year in a run-of-the-mill lecture hall setting. But he also teaches thousands — from ten year olds to retirees, in dozens of countries worldwide — on the internet. Massive open online courses (MOOCs) still face major challenges, but Ghrist’s success underscores the incredible potential they hold.

The Mathematics of Motion

Calculus is all around us, whether we’re modelling the rise and fall of the stock market or determining precisely when a spacecraft will arrive at its target. It’s the language human beings invented to describe the dynamic nature of our universe. Or as Ghrist likes to say, it’s the mathematics of motion.

Unfortunately, the vivid nature of calculus is often lost on students, whose memories of the subject usually involve long hours staring at hieroglyphs in a dense and colourless textbook. That’s why, when Ghrist was offered a grant to build a calculus MOOC in 2012, he jumped at the opportunity to try something totally different.

“When you get to start over from scratch, it opens up so many possibilities,” Ghrist says. “I was really motivated by the possibilities inherent in the visual medium, where i could use video, colour and animation to do things that are really impossible inside a college classroom.”

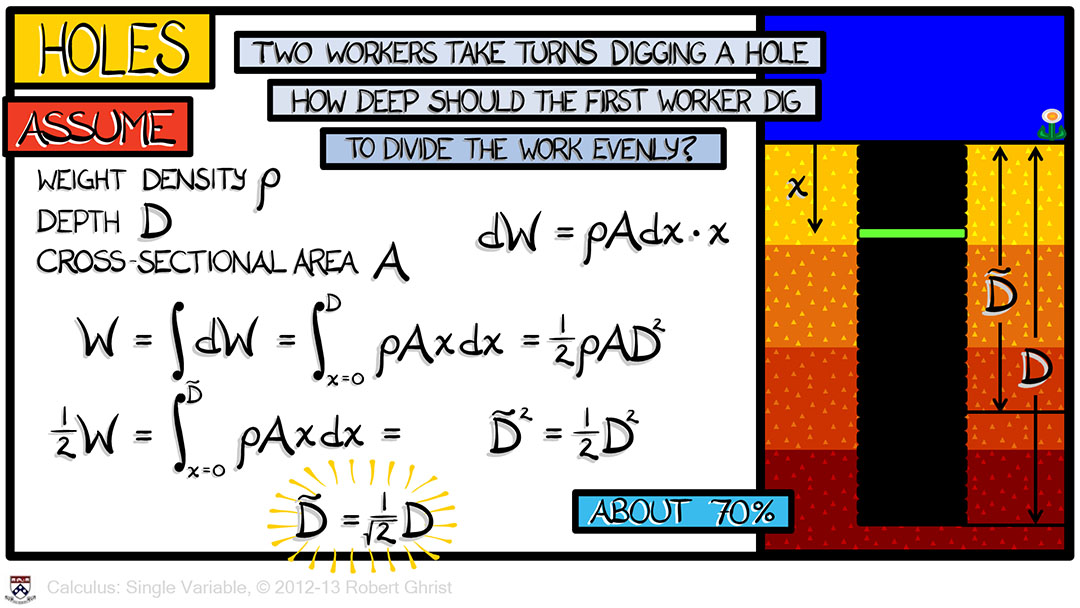

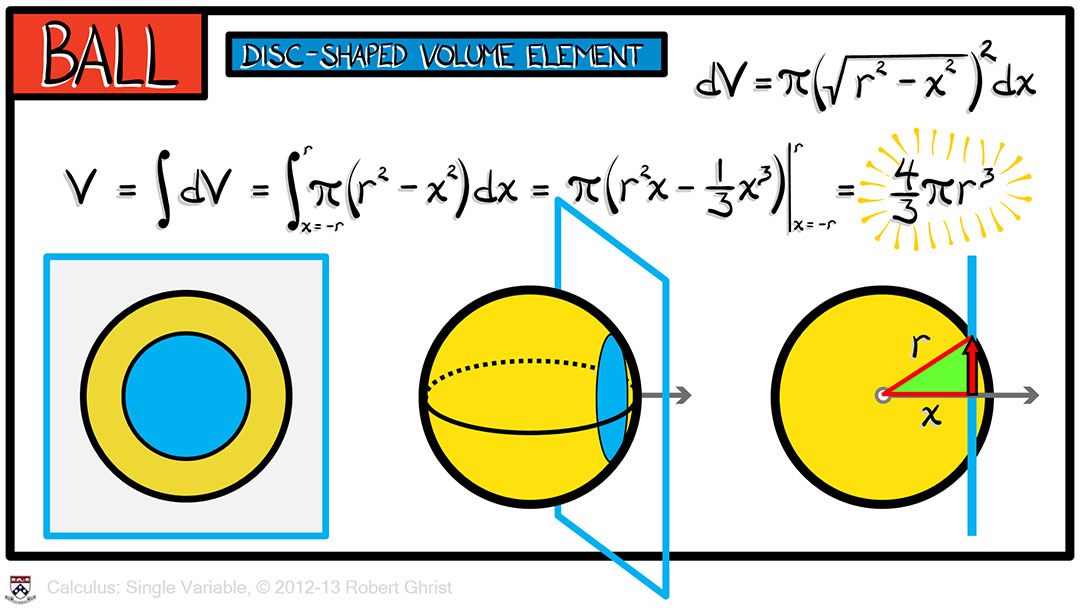

So that’s exactly what the maths professor did. Ghrist spent the summer of 2012 building “Single Variable Calculus,” a 13-week course consisting of nearly 60 vividly animated, dynamic video lessons. His main software tool? Naught but the humble Microsoft PowerPoint.

“I’m kind of a Power Point geek: it’s a great tool for building animations,” Ghrist said. “All of the stuff you see is 100 per cent powerpoint with imported graphics from, say, Adobe Illustrator.”

As someone with graphic designers and filmmakers in the family, I’ll admit I was a Power Point animation sceptic. But that was before I saw complex mathematical equations rendered as a series of sleek, colourful, and attractive animations. Sprinkle some crystal clear, professionally recorded audio tracks on top (“I obsessed over the audio,” Ghrist says), and voila, a series of calculus lectures that — dare I say it? — are pretty enjoyable to watch.

Content-wise, Ghrist’s maths MOOC stands out in a few ways. He did his utmost to make the course topical, offering myriad examples of how calc can be applied to modern science and technology, from environmental datasets to social network analysis. And to minimise the need for fancy calculators, he focuses heavily on concepts over number crunching.

“There’s no required textbook, no requirement to have any kind of calculating device other than the computer you have to interface the platform with,” Ghrist said. “The explicit goal was to make it so that anyone can take it.”

Once Ghrist was happy with Single Variable Calculus, he put it up on Coursera, a popular MOOC platform launched in partnership with several private universities, including Penn, Stanford and the University of Tokyo. He didn’t know whether anyone would take it.

Since 2013, Ghrist’s calc videos have been downloaded or streamed over two million times. At 15 minutes per, that’s over half a million hours of maths, studied across the world.

Maths for the Masses

The number of students who’ve downloaded Ghrist’s maths videos may be exceptional, but it’s equally interesting to learn who these students are. Turns out, the course has proven especially popular amongst younger and older crowds, with the typical cohort of college-age students taking a backseat.

“For my class, the majority of the people taking it are past their university education,” Ghrist says. “These are folks who are coming back, realising they didn’t learn it right the first time, that they need a refresher, and they come to get those skills levelled up.”

“I also get a bunch of gifted students who are really bored in more traditional settings,” he continued. “And I get people in retirement who just want to learn something for the fun.”

In short, Ghrist’s class is attracting precisely the people who don’t have access to a university education, but who want to learn something anyway. And the student body extends beyond countries where English is the native language. Ghrist reckons that roughly a quarter of the students come from the US, with large numbers in India, China, and Brazil. Some, tell Ghrist that they’re actually taking the course to learn English in addition to calc.

Taking and finishing a class are two different things, and Single Variable Calculus has a fairly low completion rate. Ghrist attributes this partly to the fact that it doesn’t yet come with any certification, and partly to the fact that calculus is plain hard.

“It’s a 13 week butt kicker,” he says, “and there aren’t that many people who have 13 weeks of uninterrupted time to devote to a course like this.” But Ghrist doesn’t see the low retention rate as an issue.

“The great thing about online courses is: Say you only have time for the first three weeks? Fine just do that. Then you can sign up again next time around, and do more then.”

The Future of Education?

Ghrist wasn’t the only professor who jumped into online teaching in 2012: It was “the year of the MOOC,” according to The New York Times, as several well-funded internet education startups associated with private universities emerged on the scene. Fast forward to 2015, and there now hundreds of free online courses, developed by dozens of institutions and spread across numerous platforms, including Coursera, Udacity, edX and the Khan Academy.

Picture: Shutterstock

But in the sprawling, decentralised world of online education, success is hard to define. Ghrist — whose explicit goal is to make calculus available to anyone and everyone — is happy to let the demographics and numbers speak for themselves. Other university educators would like to see hard results — and so far, those have been hard to come by. The stats we do have paint an underwhelming picture.

High dropout rates aren’t limited to online calculus — early data from Coursera showed that only 7-9% of students enrolled in a MOOC would actually finish the course and receive a grade. An online survey conducted in 2013 offers a top ten list of reasons. These include obvious culprits such like time commitment and difficulty level, but also poor course design, “lecture fatigue” (many MOOCs are simply a string of lecture videos), clunky technology, and trolling on discussion boards. Some participants cite hidden costs, including required reading from expensive textbooks written by the professor. In others cases, students signed up out of curiosity, never intending to complete the course at all.

Is all of this really a problem? After all, with minimal to no enrolment costs, if a student decides not to finish a MOOC, at least she didn’t thrown down a hefty fee. The trouble is, high dropout rates perpetuate the view that online courses are a “lesser” form of education, and that makes it harder to achieve legitimacy in the eyes of universities. Indeed, it’s still the case that only a minority of institutions offer university credit for MOOCs. And lack of certification is a problem when it comes to long-term financing, because the wave of philanthropic donations that sparked the MOOC movement won’t last forever.

“Even though we’re committed to keeping the content free for everyone, if you get a certificate at the end that allows you to go and apply for a job and gives you some kind of tangible benefit, then it’s reasonable to charge for that,” Coursera co-founder Daphne Koller said in an interview with Wharton. In other words, paid certificates might be the key to financing digital education, but the powers that be have to be convinced MOOCs are worth it.

Even online learning proponents like Ghrist don’t think the MOOC format is going to replace classrooms. “I really can’t image that given the same teacher and same material, that an online course would be better than in person,” he says. “There’s more bandwidth when you’re right there.”

“But,” he says, “if the alternative is high quality online course versus nothing, or next to nothing, it’s a clear win.”

Therein lies what may be the best argument for MOOCs: Many, many would-be learners across the world are never going to have access to a university education. It may be a utopian dream to suppose that MOOCs are going to tear down the ivory tower and unleash high-quality education on the world. But they’re certainly better than nothing.

“It is an absolute fact that the world has an incredible number of young geniuses who could do amazing things if they’re given the right opportunity,” Ghrist says. “But what are the odds that you’re fortunate enough to live in a particular order of society that recognises and values that? Think of all the missed opportunities where, over time, people were told, look, just shut up, go back out in the fields and do your job. When I think of the untapped potential we could be reaching — that makes me optimistic about the future.”

Pictures: Robert Ghrist’s “Single Variable Calculus” course