Yesterday Hyperloop Transportation Technologies filed a permit to build a 8km prototype in Quay Valley — a utopian, eco-friendly community planned for Central California. And while we’re rooting for them to succeed with their test track, it still doesn’t change the Hyperloop’s largest challenges. Because the biggest hurdle isn’t the tech behind Hyperloop, it’s the land rights and every other bureaucratic obstacle that goes along with building enormous infrastructure projects.

Back in the winter of 2013, Elon Musk announced to the world that he had a revolutionary idea about the future of transportation. He called his concept the Hyperloop, and everyone was soon excited that they’d soon zip between distant major cities at 1000km per hour. The tech press quickly picked apart the technical minutia of such a proposal, debating whether Musk’s idea was technologically possible. What so many reporters then and since have continued to ignore is that you can’t build a mode of transportation between cities like San Francisco and Los Angeles without rights to the land in between them. Not to mention the other challenges things like environmental impact reports or liability considerations.

“After over two and a half years of research and development our team has reached another important milestone. This will be the world’s first passenger-ready Hyperloop system,” Dirk Ahlborn, the CEO of Hyperloop Transportation Technologies, said in a statement released to The Verge about the plans for Quay Valley. “Everyone travelling on California’s I-5 in 2016 will be able to see our activities from the freeway.”

With every puff piece that’s published about companies like Hyperloop Transportation Technologies (not to be confused with competing company Hyperloop Technologies), everyone seems focused on the tech, rather than the real challenge: Land rights and bureaucracy. Assuming their permit is approved for Quay Valley, the idea of building a Hyperloop track between two distant cities remains a techno-utopian fantasy arguably as misguided as Quay Valley itself.

Josh Stephens makes this same point in a recent blog post:

And yet, this combination of enthusiasm and magnetism doesn’t buy farmland. It doesn’t ease eminent domain takings. It doesn’t blast through bedrock or relocate utilities. It doesn’t design station area plans. It doesn’t write [Environmental Impact Reports] or dismiss [California Environmental Quality Act] suits.

Trains, whether propelled by steam, diesel, or a frictionless tube, are still terrestrial things. And what terra we have in California. The very same mountains, cities, canals, farmers, and habitats that complicate [High Speed Rail] also complicate Hyperloop. The more the Hyperloop people drop hints and make innuendos about zipping this way and that without addressing the monumental public policy challenges that they’re going to face, governmental cooperation they’re going to need, and money that it’s going to cost, the less it’s going to sound like Tesla for the masses and the more it’s going to sound like a lost chapter of “Atlas Shrugged.”

None of this is new. Even before the official announcement back in August of 2013, I wrote an article raising scepticism that you’d be able to build a Hyperloop between San Francisco and Los Angeles without putting it underground or out in the ocean. And even then, you’d still have to get land rights and work with the government in myriad ways.

So we’ll wait with earnest optimism as Hyperloop Transportation Technologies to build a working Hyperloop prototype in Quay Valley, a planned community on virgin soil by sometime this year. But until we hear that any Hyperloop company has a legal and lobbying team as big as its tech team, we’re going to remain pretty damn sceptical that this will happen within our lifetime.

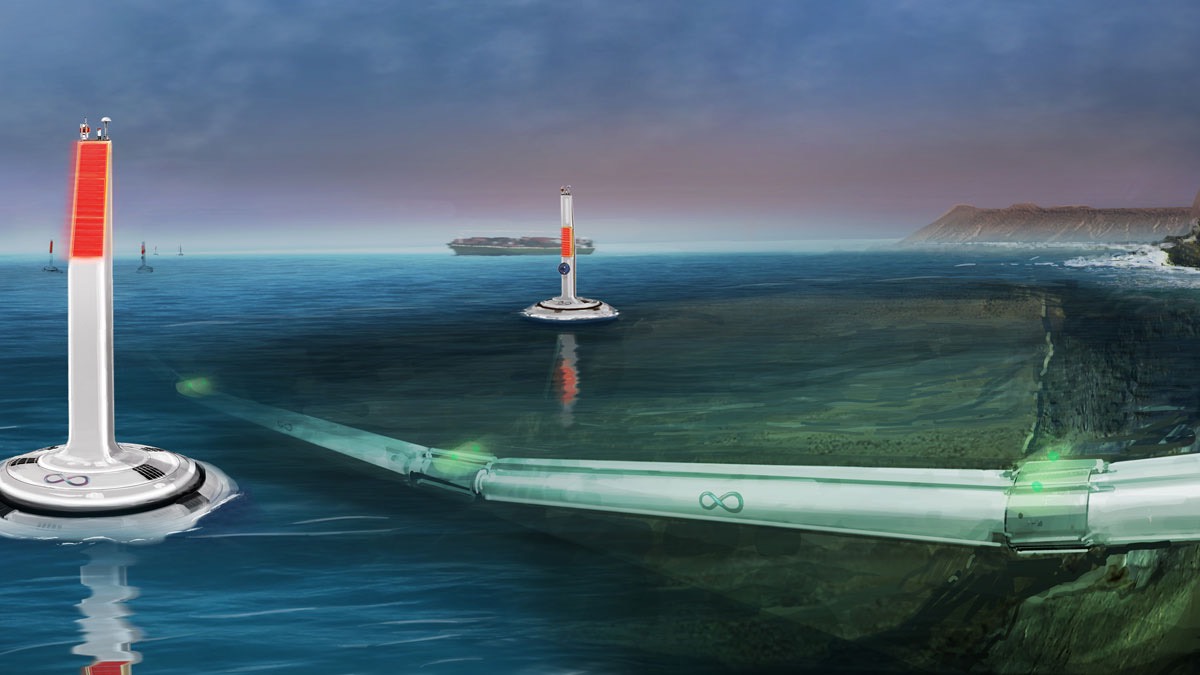

Image: Gif of Hyperloop via UCLA; Hyperloop concept drawing via YouTube