Terry Pratchett’s Discworld might look intimidating — there are 40 books, and they’re humorous fantasy, which seems like it could be an acquired taste. But everybody should read at least one Discworld book, because they’re wonderful, and there’s something for everyone. Here’s our complete guide to Pratchett’s masterwork.

What is Discworld?

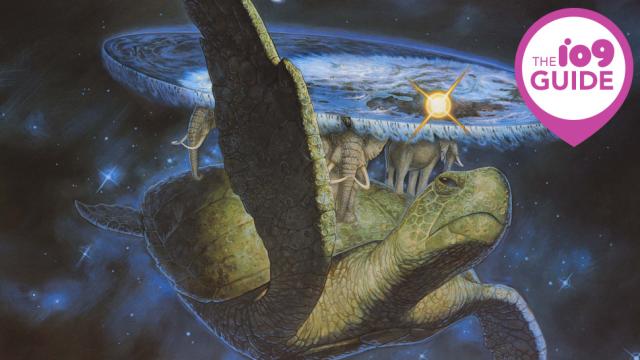

In our universe, Discworld is a series of 40 books — with one more due out this year — and assorted related projects by Sir Terry Pratchett, all set in the same fictional world. As the prologue of the first Discworld book explains, Discworld itself looks like this:

Great A’Tuin the turtle comes, swimming slowly through the interstellar gulf, hydrogen frost on his ponderous limbs, his huge and ancient shell pocked with pocked with meteor craters. Through sea-sized eyes that are crusted with rheum and asteroid dust. He stares fixedly at the Destination.

In a brain bigger than a city, with geologic slowness, He thinks only of the Weight.

Most of the weight is of course accounted for by Berilia, Tubul, Great T’Phon and Jerakeen, the four giant elephants upon whose broad and star-tanned shoulders the Disc of the World rests, garlanded by the long waterfall at its vast circumference and domed by the baby-blue vault of Heaven.

The first novel, The Colour of Magic, was published in 1983. Its sequel, The Light Fantastic, coming out in 1986. From then until 2011, there was at least one Discworld novel published every year.

Discworld takes place in the quasi-medieval fantasy realms made so famous by Tolkien. There are dangerous towns, idyllic-looking rural outposts, and dark woods with all manner of supernatural dangers. But Discworld turns those familiar elements upside down.

In fact, the early Discworld books, like The Colour of Magic and The Light Fantastic, are basically parodies of other works of fantasy fiction. Pratchett sets up fantasy tropes, and then asks, “What if the wizard was incompetent? What if the heroes were brave morons? What if our protagonist never stopped being a complete coward?”

But the later Discworld books turn into a satire of our reality, rather than just a satire of fantasy literature. “What,” asked Pratchett, “if fantasy worlds had exactly the same problems we do?” The biggest danger to Discworld doesn’t come from megalomaniacs with a desire to take over the world. Rather, it’s the little evils lurking in everyone: sexism, racism, classism — small-mindedness, in all its forms. And, because of that, the saviors don’t spring from “prophecy” or “chosen ones” — rather, salvation comes from common sense, and those who act on it.

With Discworld, Pratchett’s great achievement was to create a universe that looked as familiar as Middle Earth, and fill it with people that had more in common with recognisable, modern-day people than with Aragorn or Frodo.

Take, for example, Ankh-Morpork, the city-state that is at the center of many of the novels. Ankh-Morpork looks like King’s Landing and acts like modern London. In most stories set in the world’s most powerful city, powerful aristocrats, political intrigue, war, and would take center stage. And those things do appear in Discworld, but they are the enemy. They actively harm the city. So the hero isn’t the one who bravely goes to war, he’s the one who goes to stop it.

In the 1989 novel Guards! Guards!, a young man arrives in Ankh-Morpork, a land without a king. His whole family was slaughtered. He was raised in secret by humble miners. He has a crown-shaped birth mark and an heirloom sword. He appears destined for greatness.

Instead, he’s pushed off to the side in favour of a peasant-turned-policeman. (The descendant, in fact, of the guy who chopped the last king’s head off.) He never becomes the king. He never becomes more than a side-character, in fact. The focus of all of the books that follow is that policeman, his duty, and his struggle to keep order in a rapidly changing city while also pushing back against aristocrats telling him how things should be.

Ankh-Morpork is run by a tyrant. Lord Vetinari is a cold, calculating man with a goatee, black clothes, and a background as an assassin. He’d be the villain in a normal story. But after seeing how well he runs the city, you kind of wish Lord Vetinari — who made the Explorers’ Society rename itself the Trespassers’ Society because “most of the places ‘discovered’ by the society’s members already had people living in them” — ran our world.

All of which explains why the books are good and relevant — but leaves out just how funny they are. The climaxes of Discworld stories aren’t massive battles and vanquishing the big bad. They’re epic farces. One book’s climax actually involves a clown and a pie fight. Another hinges on a soccer game.

Pratchett uses puns, pop culture references, historical in-jokes and everything in between to create a world that is rich and ridiculous. He deploys footnotes like joke bombs. And, somehow, Discworld remains internally consistent.

It’s satire as pointed as Jonathan Swift and as modern as Stephen Colbert. On the Disc, every horrible and absurd thing is taken to its extreme end. But Pratchett doesn’t stop at highlighting things, he also gives us hope. Because these are novels — fantasy novels, even — so the good guys do succeed in the end. See, they whisper, if they can figure it out, why can’t we? If trolls and dwarfs can get along, surely we can.

As his friend and one-time co-author Neil Gaiman said just a few days after Pratchett’s death:

Terry was somebody who fought for years to try and make people understand that funny and serious are not opposites. The opposite of funny is not funny. You can absolutely be funny and serious at the same time. And Terry was.

So here’s somebody who has fought to be taken seriously and to make people realise that you can write a serious novel set in a fantasy context on a flat world on the back of elephants on the back of a giant turtle floating through space and it can still be a real novel. And he’s got there.

Gaiman also refers to Pratchett as a great mentor and the best MFA program he could get. The many, many tributes from other writers when Pratchett passed away are proof of the impact that he, and his greatest creation, had. Brandon Sanderson’s tribute also gets at the heart of what Pratchett was able to accomplish:

Of all the writers I’ve read, Pratchett felt the most human. There was more truth in a single one of his humble satires than in a hundred volumes of poignant drama. Unlike most comedians — who use their humour like a weapon, always out for blood — Terry didn’t cut or bludgeon. He was far too clever for that. Instead, he’d slide down onto the bar stool beside us, drape his arm around us, and say something ridiculous, brilliant, and hilarious. Suddenly, the world would be a brighter place.

It wasn’t that he held back, or wasn’t — at times — biting. It’s just that he seemed to elevate every topic he touched, even when attacking it. He’d knock the pride and selfishness right out from underneath us, then — remarkably — we’d find ourselves able to stand without such things.

And we stood all the taller for it.

Which Discworld Book Should You Start With?

While the books are published in rough chronological order of events on the Disc, how to start reading Discworld books is topic of constant debate. It’s generally agreed that the earlier books have some details that were changed for the better later, and that Pratchett’s writing improved after the first few novels.

Because Pratchett was so prolific in populating Discworld, there are a lot of protagonists doing different things in different parts of the world. Each book is self-contained in that it tells a whole story. The books connect, in that there is no reset button on the Disc, so the consequences of one book will hang around in others. And sometimes the protagonists of one book will cameo in others — and side characters will cameo in stories that are unrelated, except for location. But there are no trilogies or cliff-hangers in Discworld.

Ostensibly fantasy, Discworld has tackled so many different genres and topics that there is likely a Discworld book for everyone. There’s crime, romance, invention, politics, sports, and even one that acts like the Christmas special of the series. And because Pratchett covered a huge swath of ideas and tropes and topics — Unseen Academicals covers sport, Romeo and Juliet, and racism in a single book — there is a book for everyone looking for an “in” to Discworld.

As Tasha Robinson explained on NPR:

Asking “Which book will let me know what the series is like?” is akin to asking “What single fruit shall I eat to learn whether I like fruit?”

That said, the books do fit into roughly seven categories: Rincewind and the Wizards, the Witches, Death, the City Watch, Moist von Lipwig, Tiffany Aching, and the various standalones.

Rincewind and the Wizards

“Luck is my middle name,” said Rincewind, indistinctly. “Mind you, my first name is Bad.”

Rincewind is the central character in the first two Discworld novels, a failed wizard from Unseen University (think the Oxford of magic). Rincewind is as cowardly as he is bad at wizardry, and yet somehow always finds himself in the middle of grand adventures that he desperately wishes were happening to someone else. He’s a reluctant hero who never stops being reluctant, a cowardly protagonist who never graduates to bravery.

The wizards of Discworld are usually represented by the staff and students of Unseen University. Every issue of academia and the bureaucracy of any large organisation or corporation is represented by way that the wizards run themselves.

People with strong knowledge of typical fantasy tropes and academia might find Rincewind and the wizards a good starting point. And if you have a sports fan in your life, go with Unseen Academicals.

Books:

The Colour of Magic (1983); The Light Fantastic (1986); Equal Rights (1987); Sourcery (1988); Faust Eric (1990); Lords and Ladies (1992); Interesting Times (1994); The Last Continent (1998); The Last Hero (2001); Unseen Academicals (2009)

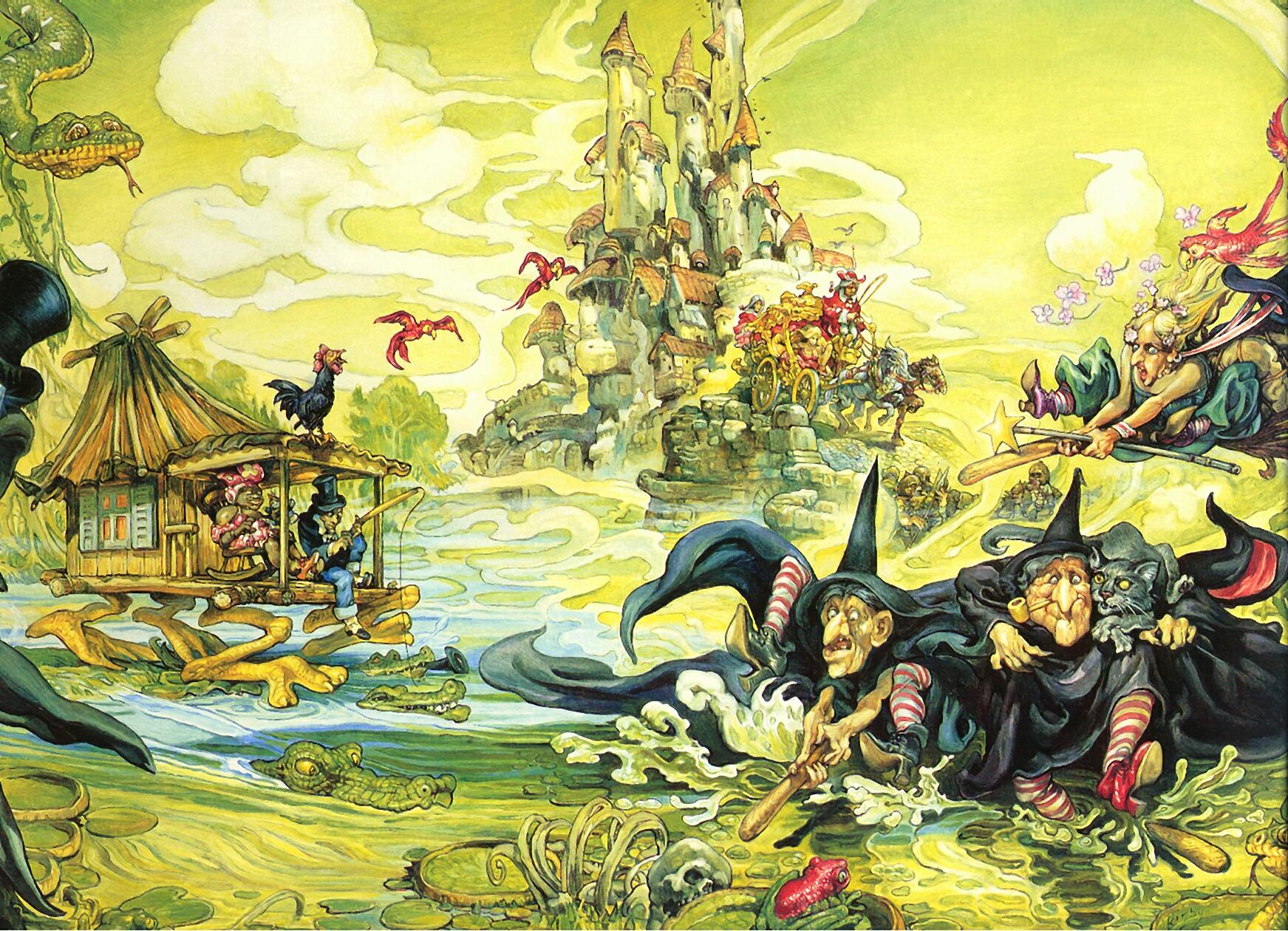

The Witches

“Witches just aren’t like that,” said Magrat. “We live in harmony with the great cycles of Nature, and do no harm to anyone, and it’s wicked of them to say we don’t. We ought to fill their bones with hot lead.”The other two looked at her with a certain amount of surprised admiration. She blushed, although not greenly, and looked at her knees.”Goodie Whemper did a recipe,” she confessed. “It’s quite easy. What you do is, you get some lead, and you — “

“I don’t think that would be appropriate,” said Granny carefully, after a certain amount of internal struggle. “It could give people the wrong idea.”

“But not for long,” said Nanny wistfully.

The witches of Discworld use a form of magic very different from the very theoretical version of the wizards. The witches use common sense, hard work, and “headology” — a form of psychology. They have the power of First Sight — seeing the world as things actually are and not what you want it to be — and Second Thoughts — thinking about thinking.

Like Rincewind, who upends the idea of wise and guiding wizards in fiction, the witches of Discworld upend the idea of fairy take witches and crones. They puncture traditional stories with practicality. The main witches the books follow are the members of the Lancre coven — Lancre being a based on rural England.

People with an interest in fairy tales, witchy archetypes, and romance will probably find the witches a fulfilling place to start.

Books:

Equal Rites (1987); Wyrd Sisters (1988); Witches Abroad (1991); Lords and Ladies (1992); Maskerade (1995); Carpe Jugulum (1998)

Death

I AM DEATH, NOT TAXES. I TURN UP ONLY ONCE.

Not the abstract concept — but the personification of Death as the typical skeleton in a black robe, wielding a scythe. Death talks LIKE THIS and has the most appearances of any Discworld character — every book except two. Death is a studier of humans and can seem like a kindred spirit to Data in Star Trek: The Next Generation. He’s both fascinated and baffled by humanity, and thus will try to protect humans, insomuch as the rules of his existence will let him.

Death, for all his typical trappings, is a bit eccentric. He really likes cats, his pale horse is named Binky, and he’s given the aspect of himself that deals with rats independent existence as the Death of Rats. (The Death of Rats SQUEAKS.) There’s also Quoth the Raven, a joke you’d think would get old but never does.

Death’s fascination with humans allows Pratchett to cover creativity, imagination, and belief in Death’s books. They also have a strong element of fish-out-water tales of Death trying to do human things.

There is probably not a more beautiful nontheistic defence of Christmas and Santa Claus than the one Pratchett has Death give in Hogfather.

Books

Mort (1987); Reaper Man (1991); Soul Music (1994); Hogfather (1996); Thief of Time (2001)

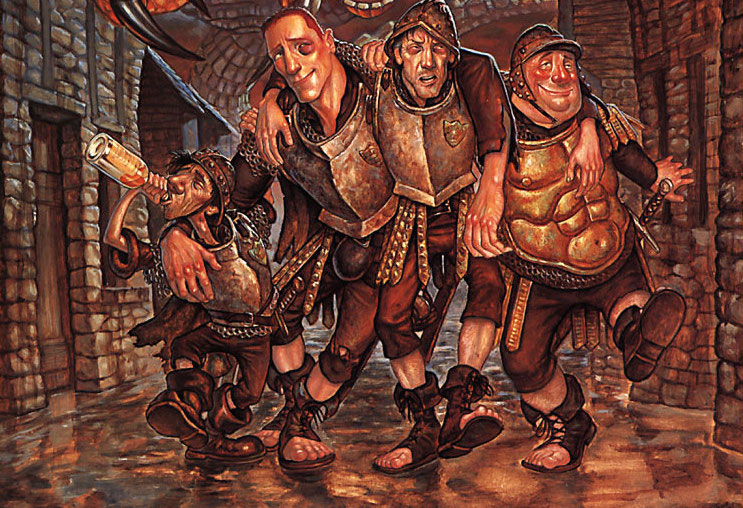

The City Watch

Cheery was aware that Commander Vimes didn’t like the phrase ‘The innocent have nothing to fear’, believing the innocent had everything to fear, mostly from the guilty but in the longer term even more from those who say things like ‘The innocent have nothing to fear.’

The City Watch epitomize the switch in Discworld novels from parody to satire. Their first appearance in Guards! Guards! is supposed to be part of a larger parody of fantastical dragons and lost kings and tyranny, about the heir to the throne who’s too good to be believed. But Sam Vimes, commander of the Night Watch, shows up and hijacks the whole thing. While still funny, the Watch books get progressively darker as Vimes and his watch contend with bigger and bigger societal ills.

Sam Vimes is a wonderful creation. He’s a man who holds on to what’s right by pure force of will, holding back the darkness inside him in order to do his duty. He’s like an anti-superhero, bypassing vigilanteism. Even though it would be easierand he may be morally in the right, Sam Vimes doesn’t bend. Who watches the watchmen? Sam Vimes does.

Books:

Guards! Guards! (1989); Men at Arms (1993); Feet of Clay (1996); Jingo (1997); The Fifth Elephant (1999); Night Watch (2002); Thud! (2005); Snuff (2011)

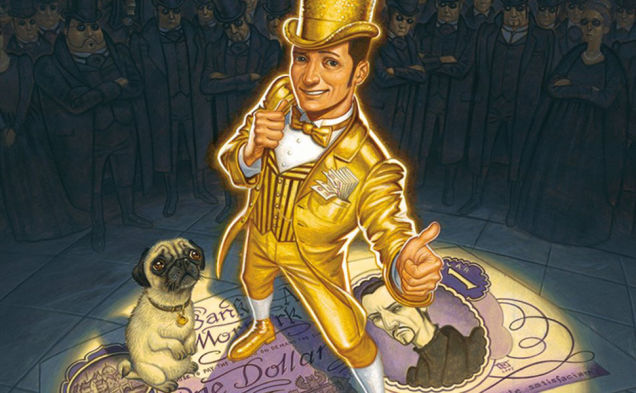

Moist von Lipwig

Steal five dollars and you’re a common thief. Steal thousands and you’re either the government or a hero.

Like the City Watch books, Moist von Lipwig’s trilogy is set in Ankh-Morpork. And just as Sam Vimes stumbled into bigger issues through investigating crimes, Moist von Lipwig bumps into them by being a con man in need of a challenge. Moist is a con man, who loves the game more than the money, and when he gets caught, he’s essentially drafted by Ankh-Morpork’s tyrant, the viciously smart Lord Vetinari, into running the Post Office, the banking industry, and the trains.

Not just very good satire, Pratchett uses Moist’s books to explain issues of public vs. private enterprises, corporate takeovers, banking crises, gold-backed currency, intellectual property, and even terrorism. And he does it better than many professors and politicians have been able to.

As good and as relevant as they are, the Moist books are the culmination of the other Discworld — especially the Ankh-Morpork-set — books. They are enriched heavily by being read later. Although, as with all Discworld books, they stand on their own.

Books:

Going Postal (2004); Making Money (2007); Raising Steam (2013)

Tiffany Aching

Tiffany knew what the problem was immediately. She’d seen it before, at birthday parties. Her brother was suffering from tragic sweet deprivation. Yes, he was surrounded by sweets. But the moment he took any sweet at all, said his sugar-addled brain, that meant he was not taking all the rest. And there were so many sweets he’d never be able to eat them all. It was too much to cope with. The only solution was to burst into tears.

Tiffany Aching is Discworld’s entry in the Young Adult category of fiction. She begins her books as a nine-year-old and was last seen at the age of sixteen, with her stories bringing her into the world of the original witches’ books as she gets older. As is the case with stories with young protagonists, the stories hit the themes of adolescence, being a teenager, growing up, and identity. The third book also has a strong does of the Persephone and Orpheus myths thrown in.

Books:

The Wee Free Men (2003); A Hat Full of Sky (2004); Wintersmith (2006); I Shall Wear Midnight (2010); The Shepherd’s Crown (Autumn, 2015)

Assorted Standalone Novels

Those are all the books with the same main characters, but there are also a bevy of more standalone novels, each connected to the main universe and having an effect on the books published after them.

Pyramids (1989): Spend some time in Discworld’s version of Ancient Egypt, with another of Pratchett’s takes on belief.

Moving Pictures (1990): The movie industry invades Discworld.

Small Gods (1992): Religion

The Truth (2000): The Press — who have cameos in many other books.

The Amazing Maurice and his Educated Rodents (2001): Another Young Adult novel, with a talking cat, his trained mice, and their human accomplice. It’s a take on the Pied Piper story and parody of folk tales.

Monstrous Regiment (2001): What happens in Discworld when the “woman disguised as a man joins the army” trope hits. Themes of war and women’s rights.

Discworld is a rich world that Terry Pratchett devoted thirty-two years to developing and growing. It offers many types of storytelling, but all of them are rich with insights and humour. Once you find the right entry point to the series, it’s almost impossible to not go seek out the rest. So, if you haven’t read a Discworld book yet, go do it.