A cognitive psychologist at McGill University has scanned the brain of Grammy-winning musician Sting to glean insight into how creative people find connections between seemingly very different thoughts or sounds. The results were just published in Neurocase.

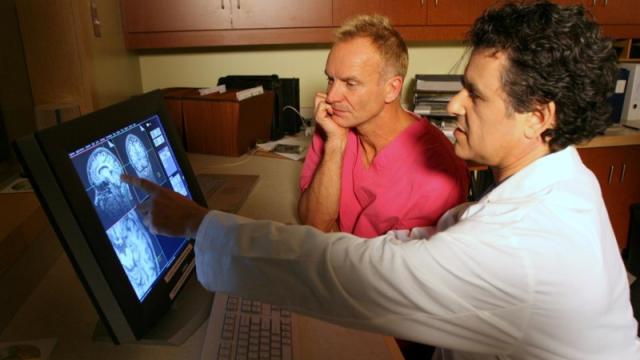

Don’t scan so close to me: Neuroscientist Daniel Levitin shows Sting his cerebellum. (Image: Owen Egan)

It all started a few years ago, when Sting was travelling to Montreal to play a concert. He had read McGill professor Daniel Levitin’s best-selling book, This Is Your Brain on Music, and being the curious type, had his rep contact Levitin and ask for a tour of the lab. (Prior to becoming a neuroscientist, Levitin was a session musician, sound engineer and producer, so there’s a natural affinity.) Levitin offered to scan Sting’s brain during the visit. Naturally the singer-songwriter said yes.

Things didn’t exactly go off without a hitch on the day of the visit. There was a power outage, for starters, that knocked out the power on the entire McGill campus for several hours. That meant rebooting the fMRI machine — which can take an hour or so. Sting had to skip his soundcheck, but in the end they got the scan done, capturing the musician’s brain in the act, so to speak, as he listened to a wide range of music: Pop songs, jazz, R&B, tango, rock, even Muzak.

Then, Levitin teamed up with the University of California, Santa Barbara’s Scott Grafton for the arduous task of analysing the data. Specifically, they used a couple of novel techniques to determine which songs Sting found similar to each other, and which ones he didn’t.

“These state-of-the-art techniques really allowed us to make maps of how Sting’s brain organizes music,” Levitin said in a statement. “That’s important because at the heart of great musicianship is the ability to manipulate in one’s mind rich representations of the desired soundscape.”

Among the most interesting findings: “Sting’s brain pointed us to several connections between pieces of music that I know well, but had never seen as related before,” said Levitin. For instance, Piazzolla’s “Libertango” and the Beatles’ “Girl” are both in minor keys and include similar motifs in the melody. Also, the Sting-penned “Moon Over Bourbon Street” showed strong connections in key, tempo and swing rhythm with “Green Onions” by Booker T and the MG’s.

In general, the Muzak and Top 100 pop songs were distinct from other musical styles like jazz, R&B, tango and rock, which tended to cluster together. Furthermore, “The act of composing, and even of imagining elements of the composed piece separately, such as melody and rhythm, activated a similar cluster of brain regions, and were distinct from prose and visual art,” the authors concluded.