If you’ve ever been to a foreign country where you don’t speak the language, you know that an inability to communicate can be frustrating, if not a bit scary. But in Arrival, when 12 shell-shaped UFOs land across the world, everything seems to hinge on the skills of Amy Adams’ linguistics expert, Louise — just as the movie itself hinges on making communication compelling.

It was up to screenwriter Eric Heisserer and production designer Patrice Vermette to not only bring Ted Chaing’s short story “Story of Your Life” to the screen, but also to create the language the aliens used — and then translate all of it into a gripping drama. Having seen the movie, which opened last week, we can tell you they succeeded. Here’s how.

Arts and Language

Arrival‘s aliens are heptapods: Massive, seven-legged creatures with wrinkly skin whose voices sound like a combination of a whale call and a large cat’s purr. Hired by the US military to work at the Montana site where one spacecraft has landed, linguist Dr Louise Banks (Adams) determines that interpreting their spoken words, dubbed Heptapod A, will be slower and more difficult than their written language, designated Heptapod B. Speed is obviously of the essence here, as Colonel Weber (Forest Whitaker) is anxious to get an answer as to why these aliens have come to Earth.

In Chiang’s short story, the heptapods’ written script is described as “vaguely cursive”. Heisserer and took on the task of more fully developing an alien language. Eventually, the filmmakers had a dictionary of 100 Heptapod B logograms. So it isn’t a completely realised language like Lord of the Rings‘ Elvish, but J.R.R. Tolkien did influence Heisserer’s process. He took a close look online at graphics of the One Ring etchings, and decided he had to make Heptapod B circular to underscore the eventual twist about the aliens that comes late in the film.

Vermette tackled the detailed work of designing the language as it would appear onscreen, where the heptapods produce their script onto a glass-like panel inside their ship with ink from one of their legs. The Canadian production designer worked out the mechanics of the language — what each curl and blot meant — but it was Vermette’s wife, conceptual artist Martine Bertrand, who conceived the actual look of the alien font.

“She came up with the inky, smoky, what we often refer to as the coffee stain version of the language,” Arrival producer Dan Levine told us. “It moved away from what I think [director] Denis [Villeneuve] felt was a placeholder in the script, [which was] a little too techy-looking. He wanted something more natural.” Soon Heptapod B was ready for their linguist hero — and a real-life linguist.

Heisserer included graphics of the Heptapods written language directly into the script.

Truth in Linguistics

Jessica Coon never expected to find herself attempting to translate an extraterrestrial language. A linguistics professor at McGill University (near where Arrival was filmed in Montreal), whose research primarily deals with the Mayan language Ch’ol, Coon consulted on the film and even played out some of the work Louise does onscreen.

“With the logograms at some point, they sent me a stack of them and they said, ‘OK, figure it out,’” Coon recalled. “I said, ‘What are you talking about?’ And they said, ‘Well, imagine, it’s your job — here’s what you’ve got. Decipher them.’ And of course I didn’t have heptapods to interact with, but there are patterns in the logograms. They wanted me to just annotate them as a linguist would.”

Those annotations influenced the markings in red pen Louise makes on large print-outs of Heptapod B during the long hours she works in military tents, studying the language she’s seen in face-to-face sessions with the heptapods aboard their ship.

Much of Coon’s role was making sure the film’s depiction of linguists and translation is accurate. “The biggest thing for me as a writer is I need the expert to come in as the police, to make absolutely certain that we haven’t violated anything in their profession and present that as accurately as possible,” Heisserer said.

To create Louise’s office at an unnamed university, the set decoration team turned to Coon’s McGill office, taking photos and borrowing books that ended up on Louise’s shelves onscreen. “It looks amazingly like a McGill linguistics office,” Coon said.

The grunt work of linguists and translators doesn’t naturally make for action-packed entertainment, though, and “Story of Your Life” is highly scientific, not inherently cinematic. So Heisserer had the challenge of making the adaptation Hollywood-ready.

Making Communication Cinematic

Heisserer made a few changes early on to “Story of Your Life” to bring it to the big screen. In the short story, the heptapods never do land on Earth — they’re communicating with Louise and other linguists and scientists via digital screens they have sent light years across the universe. Heisserer knew he had to get his hero face-to-face with the heptapods. He also added a pulse-pounding third act finale that doesn’t appear in Chaing’s 1998 story.

Meanwhile, the nitty-gritty work of interpreting Heptapod B was largely moved to a montage scene with voiceover by Jeremy Renner, who plays Ian Donnelly, a theoretical physicist also hired by the military for the Montana site.

A brief moment in that montage when Ian and Louise are teaching the heptapods basic vocabulary words was originally a larger part of the script. But producers Levine and Dan Cohen of 21 Laps (the company behind Stranger Things) were quick to have screenwriter Heisserer change his approach to that moment.

“One of the very first major notes I got from [Levine and Cohen] was on a series of scenes in which Louise is teaching very basic vocabulary to the heptapods,” said Heisserer, who wrote Arrival on spec. “Ian is demonstrating ‘walks,’ ‘eats,’ ‘shakes hand,’ whatever it is. So the list of vocabulary was super-boring, obviously. And right off the bat the Dans said, ‘Eric. This is not sexy at all.’”

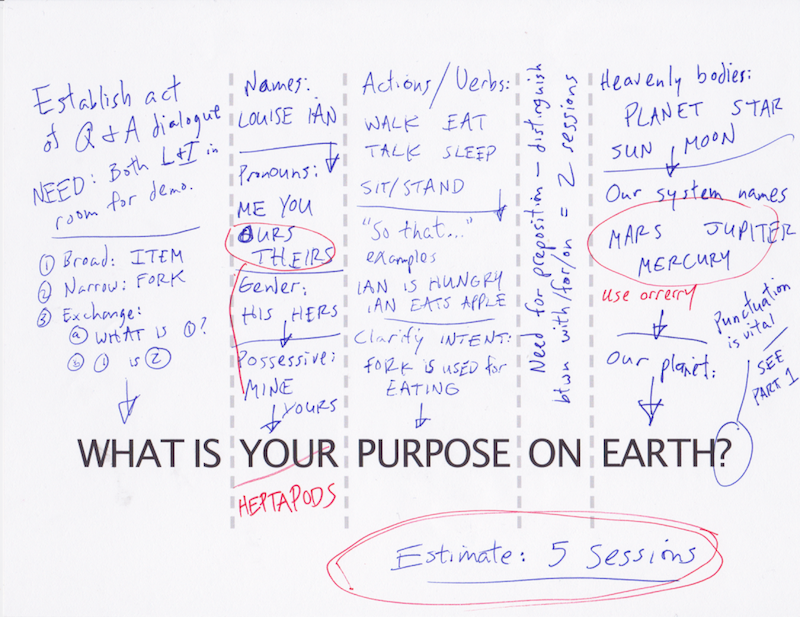

But Heisserer knew he had to impress upon his producing partners just how much work it would take for a linguist to ask the heptapods, “What is your purpose on Earth?”

So he jumped up off the couch in 21 Laps’ office, grabbed a marker, and wrote “What is your purpose on Earth?” on the white board. He diagrammed the sentence and told Cohen and Levine he estimated it would take five sessions with the heptapods to know enough of their language to ask the crucial question. (Louise ends up speaking with the heptapods and studying Heptapod B for weeks before being ready to ask the question.)

The actual white board notes written by Heissere.

“I wrote all this in their office, and at the end of me going on this long list of ‘This is why you need to do this and this,’ and of course you need to have enough vocabulary to get an answer so you know what they’re saying. And they stared at me for a beat and said, ‘That scene should be in the movie. That’s the one!’”

The answer to that question — “What is your purpose on Earth?” — is central to the big reveal of Arrival.

All the Time in the Universe

The heptapods’ written language uses non-linear orthography. Its circular structure has no forwards or backwards direction, and the heptapods can in mere seconds ink a complex “sentence”.

Once Louise has spent weeks learning, thinking in and even dreaming in Heptapod B, she begins to perceive time as the heptapods do: Non-linearly. They are able to experience more than one moment of their lives at once, and they can see far into their own futures. Arrival‘s audiences have also had their own notion of time turned on its head by the end of the film: Louise’s flashbacks about her daughter are, in fact, flash forwards.

The way Louise thinks and perceives our world is directly shaped by the structure and other properties of the heptapods’ language. This is a linguistics concept-paradigm called the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, also known as linguistic relativity, and is the idea at the heart of Arrival.

The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis is based on the early 20th-century work of American linguists Edward Sapir and Benjamin Lee Whorf. Sapir theorised in 1929: “Human beings… are very much at the mercy of the particular language which has become the medium of expression for their society… The fact of the matter is that the ‘real world’ is to a large extent unconsciously built up on the language habits of the group.”

In the real world, studies suggest Russians have stronger colour discrimination because their language has different words for “light blue” and “dark blue”. But that’s one of scattered, small instances of how language shapes or reveals people’s perceptions of reality. In fiction, the Sapir-Whorf has inspired several works: Ayn Rand’s Anthem takes place in a dystopian society where the concept of individuality has been eradicated by eliminating singular personal pronouns like “I”. In Ursula K. LeGuin’s 1974 novel The Dispossessed, there is no concept of owning property on an anarchist planet where the language lacks possessive case.

The hypothesis is fascinating, but linguists believe it is problematic to apply to differences in human languages. “In a lot of representations of this, there is sort of a romantic view of other languages and how having different terms might influence how people see the world,” Coon told us. “But there’s also a dangerous side of this if we start thinking about other cultures or other people being so radically different from us.”

Most modern linguists also contend that the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis is just plain wrong. As Columbia University linguistic professor John McWhorter asserts in his book, The Language Hoax, published earlier this year, language reflects culture and worldview, not the other way around.

Why They have Come to Earth

But in Arrival, the heptapods’ language is a gift, and one they have come to Earth to give its inhabitants. But according to the alien Louise and Ian have affectionately named Costello, it also comes with the plea that humans help the heptapods in 3000 years. However, this wasn’t the original answer to “What is your purpose on Earth?”

“For a couple of years [during writing], the gift they gave us were pieces of technology that when we put them together, we could build an interstellar ship similar to theirs and travel around and get off this rock,” Heisserer said. In those drafts, Arrival delved into Bayes’ theorem applied to global population.

But when Heisserer and his fellow filmmakers realised that the upcoming film Inferno also dealt with issues of overpopulation, and that Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar was also centred around building a ship to get humanity off a dying Earth, they changed their minds — and the script.

“Denis [Villeneuve] and I had a long coffee meeting, like we were prone to do,” Heisserer recalled, “and he said, ‘You know, we have the gift right here, which is the language, the ability to see our own future and see our own timeline in a different way.’”

Looking Back to the Future

Though the application of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis to human languages may have problematic implications in reality, in Arrival, the idea that another species can see time differently inspires the audience to think about how we do respond to the experience of getting a glimpse, so to speak, of our future. Chiang says in the story notes of a collection of his works he wanted to “tell a story about a person’s response to the inevitable”.

Louise knowing her future means she has to, all at once, grapple with the birth and death of her daughter. She falls in love with Ian even though she’s already seen how their marriage ends in divorce. Toward the end of the film, Louise ponders, “If you could see your whole life from start to finish, would you change things?” It turns out she can’t change things, though free will paradoxically coexists with her ability to see her future. But she concludes at the end of the film, “Despite knowing the journey and where it leads, I embrace it, and I welcome every moment of it.”

When we asked Heisserer if he would want the same type of knowledge that Louise and the Heptapods do, he answered, “I think I can only be enriched by a greater perspective on the world. And a greater perspective on time would certainly do that. I don’t think it would necessarily mean I would change my own life.

“I fall in the Louise category of I have regrets, but I know the regrets I have from things helped mature me and helped me be a better person now. Where past me may have been an arsehole at times, it’s important for me to be able to grow that way.”