Imagine a biosensing contact lens that can tell when your blood sugar is getting too low, or if there’s something wrong with one of your organs. By leveraging the power of ultra-thin transistor technology, researchers from Oregon State University have taken us a step closer to achieving that goal.

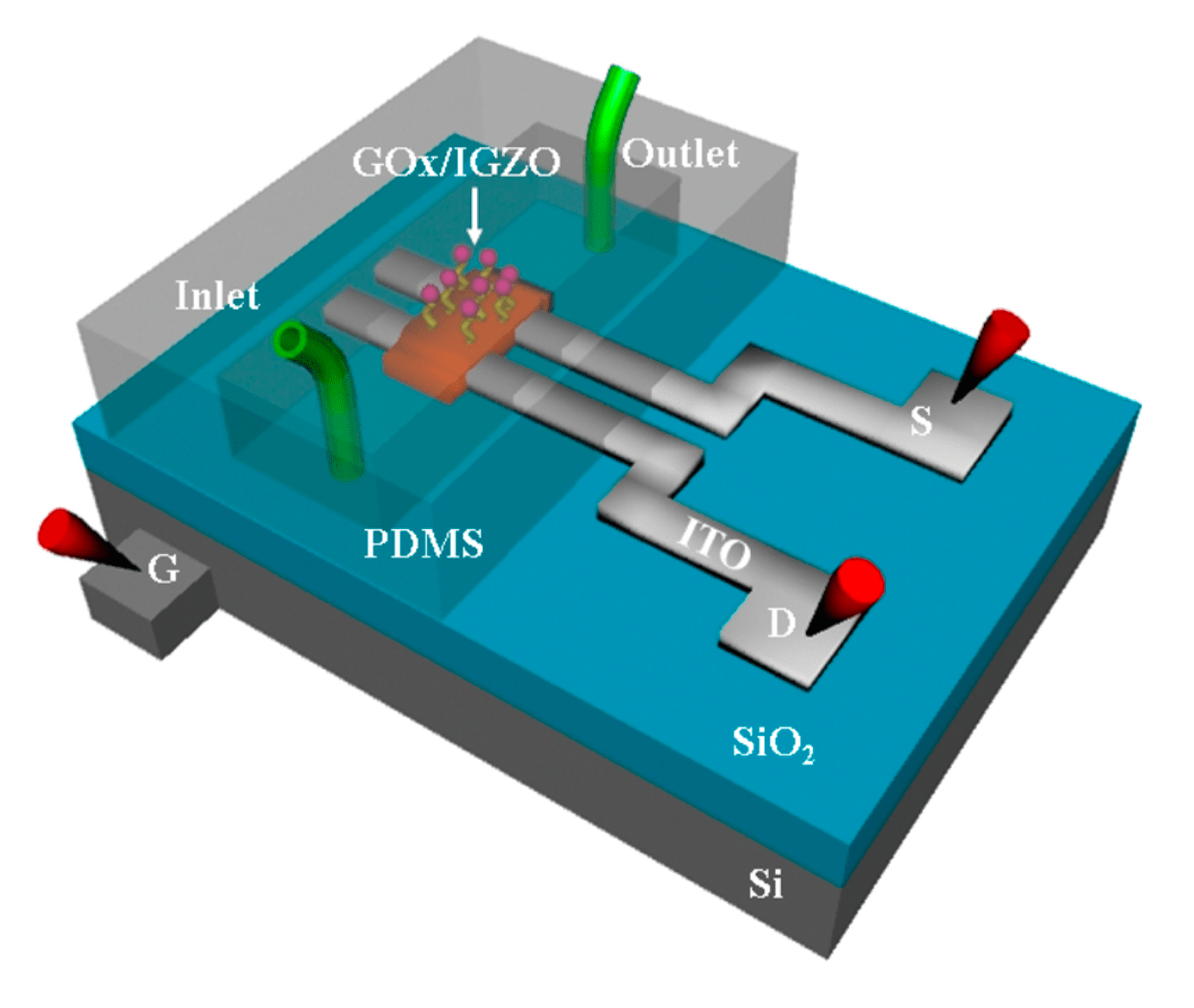

Artist’s depiction of the biosensing contact lens. Ideally, the lens and its components will be completely invisible. (Image: Jack Forkey/Oregon State University)

A research team led by Oregon State professor Gregory Herman has developed a transparent biosensor that, when added to a contact lens, could conceivably be used to detect symptoms an array of health conditions. Currently, a lab-tested prototype can only detect blood glucose levels, but in the future, the team believes it could detect other medical conditions, possibly even cancer. It will be a few years before we see such futuristic contact lenses on pharmacy shelves, but the technologies required to build this noninvasive diagnostic device largely exists today. This research was presented today at the 253rd National Meeting & Exposition of the American Chemical Society.

When he embarked on the project, Herman was looking for a better way to help people with diabetes. Today, diabetics can continuously monitor their blood glucose levels with electrodes implanted under the skin. The trouble is, this form of monitoring can be painful and cause skin irritations and infections. A disposable, biosensing contact lens would be more practical, safer, and far less intrusive.

To get started, Herman piggybacked off an idea he and his colleagues came up with a few years ago — a semiconductor composed of the compound gallium zinc oxide (IGZO). This is the same semiconductor that has revolutionised electronics, allowing for higher resolution televisions, smartphones and tablets. Herman now wants to apply a similar technology to diagnostic medicine.

To make the prototype contact lens, the researchers fabricated a biosensor containing a transparent sheet of IGZO transistors and glucose oxidase — an enzyme that breaks down glucose. When this biosensor comes into contact with glucose, the enzyme oxidises the blood sugar. This causes the pH level in the mixture to shift, triggering measurable changes in the electrical current flowing through the IGZO transistors. Tiny nanostructures were embedded within the IGZO biosensor, allowing the transparent device to detect minute glucose concentrations found in tears.

Herman estimates that more than 2500 biosensors could be embedded in a 1mm square patch of an IGZO contact lens, each of them designed to measure a different bodily function.

“There is a fair amount of information that can be monitored in a teardrop,” Herman told Gizmodo. “Of course, there is glucose, but also lactate (sepsis, liver disease), dopamine (glaucoma), urea (renal function), and proteins (cancers). Our goal is to expand from a single sensor to multiple sensors.” As noted, the current model can only test for glucose, so only time will tell if the technology can be leveraged to sniff out these other chemicals.

The sensor is still in the development phase, and it has yet to be attached to a contact lens. Eventually (and ideally), a souped-up version of this device will transmit data via radio frequency (RF) to a receiver. As a bonus, the RF signals will also power the device; in future, a tiny antenna will be used to charge the capacitor. Currently, the prototype is not transmitting data outside of the sensor, and scientists take readings by measuring the electrical current flowing through the device.

Herman said that his team’s solution is quite similar to the one proposed by Google back in 2014, but he believes his team can make all the components completely invisible. Instead of the transparent IGZO transistor, Google’s “smart lens” utilises a tiny wireless chip and a miniaturised glucose sensor that’s embedded between two layers of soft contact lens material.

Given that contact lenses are disposable, these devices need to be affordable. But Herman doesn’t see this as a problem. “We are using a technology that is very similar to what is used for cell phones, the IGZO thin film transistors,” he said. “One hundred transistors in a cell phone display is going to cost less than ten cents.” Encouragingly, Herman and his colleagues developed an inexpensive method to make IGZO electronics, but as he himself admits, “there are other costs that will need to come down”. The affordability of these hypothetical devices is still an open question.

Ideally, the researchers would like to start testing their biosensing contact lens on animals in about a year. As noted, Herman’s team presented their findings at an ACS meeting today, but their research has already appeared in the science journals Nanoscale and Applied Materials & Interfaces.