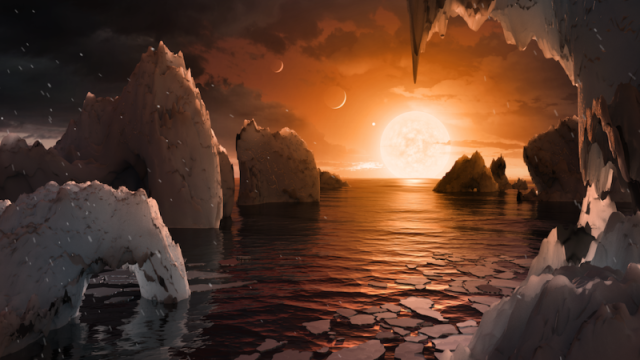

In February, Earthlings rightfully cheered when NASA announced the discovery of seven Earth-like planets huddled together around an ultracool dwarf star. The system, called TRAPPIST-1, is especially appealing because it has three planets in the habitable zone, meaning their surfaces could hypothetically support liquid water and even life. As a result, everyone from seasoned astronomers to tinfoil hat believers (*raises hand*) wants to get a piece of that sweet TRAPPIST-1 pie and find some alien babies. But sadly, our hopes might already be dashed. Only a little. Maybe.

Image: NASA/JPL-Caltech

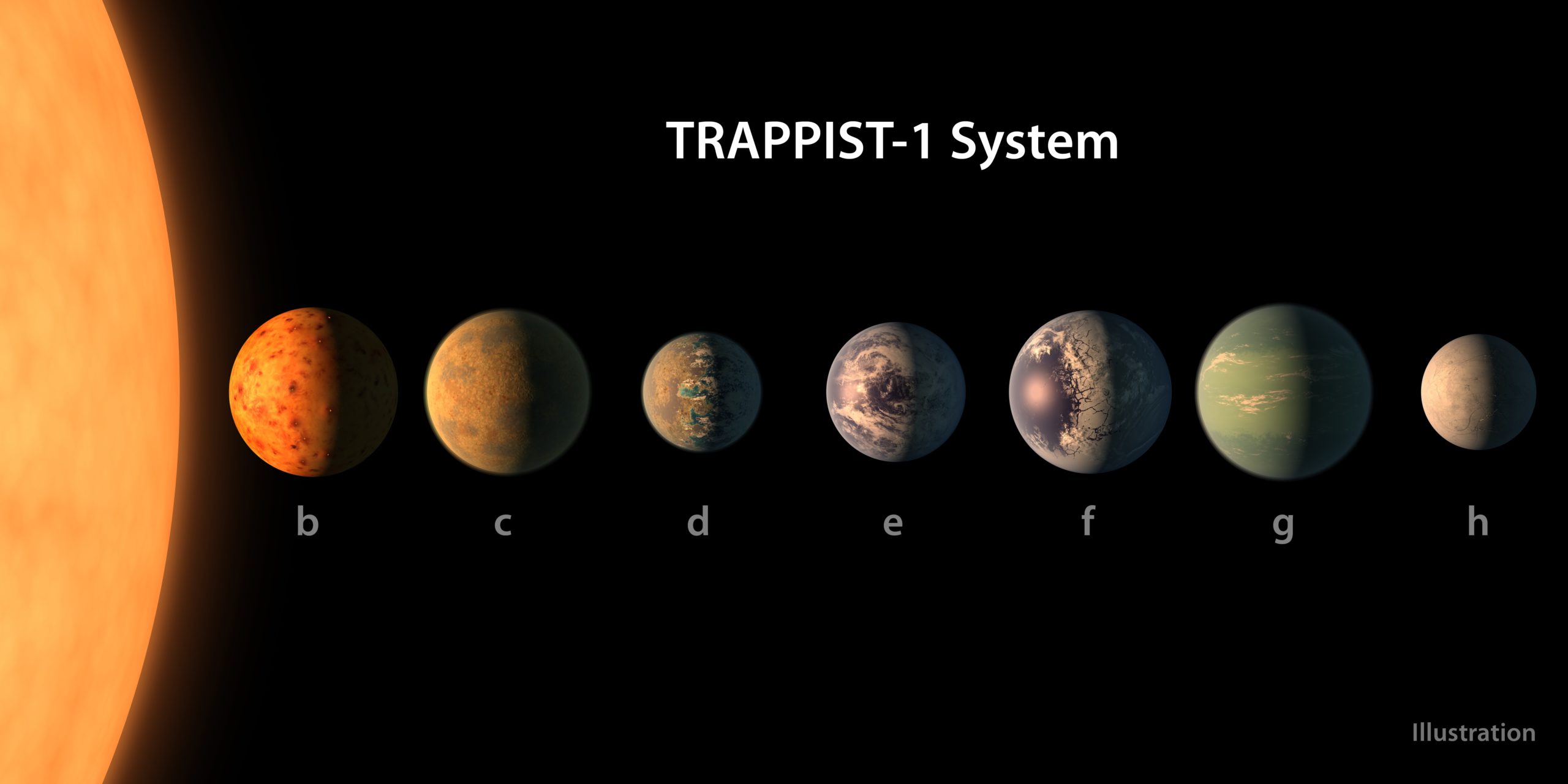

A new study from a team of scientists at the Konkoly Observatory in Budapest, Hungary has revealed what could be the Achilles’ heel for the TRAPPIST-1 exoplanets: Solar flares from the host star causing chaos in the planetary atmospheres. Using data from NASA’s Kepler spacecraft’s K2 mission, the team observed the TRAPPIST-1 system’s light curve over a period of 80 days. In that relatively short window, the researchers noted 42 solar flare events, which could make the TRAPPIST-1 planets’ atmospheres too unstable to sustain life. The team’s bummer study is set to be published in the Astrophysical Journal.

To add a kilogram of salt to this gaping wound, the researchers think storms in the TRAPPIST-1 system “can be 100 to 10,000 times stronger than the most powerful geomagnetic storms on Earth”. The largest solar storm ever recorded on Earth, the Carrington Event of 1859, caused unprecedented geomagnetic disturbances. Experts say that a repeat performance “would devastate [the] modern world,” according to National Geographic. Large solar flares are dangerous because they send off high energy radiation (for example, X-rays and ultraviolet light) that can strip a planet’s atmosphere and harm any life forms huddled beneath it.

So unless alien life resembles this guy or this guy, TRAPPIST-1 might be screwed — or at least, our chances of finding signatures of life in those seven exoplanet atmospheres might be shot.

Image: NASA/JPL-Caltech

But of course, not all hope is lost. Scientists have warned that the Proxima Centauri system, our nearest neighbouring star which hosts the recently-discovered exoplanet Proxima b, might also have habitability issues because of the radiation its M dwarf star spits off in violent outbursts. But according to some experts — namely, astrobiologists — this doesn’t discount the possibility of life on Proxima b. The same goes for TRAPPIST-1.

“I think what [these researchers] have thought about is mostly atmospheric biosignatures, and so if the atmosphere doesn’t stabilise it’s going to be hard to detect if those are there,” Lisa Kaltenegger, Director of the Carl Sagan Institute, told Gizmodo. “But for the other biosignatures like biofluorescence, it doesn’t matter so much what the atmosphere does.” Here on Earth, certain kinds of marine animals like jellyfish and coral use biofluorescence to cope with intense solar radiation, by absorbing high energy rays and reemitting lower energy and a distinct colour.

Recently, Kaltenegger and her colleague, Carl Sagan Institute research associate Jack T. O’Malley-James, published a paper in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society about how potential biofluorescent life on TRAPPIST-1 planets might survive whether or not their atmospheres are unstable due to large solar flares.

“There’s a lot more resilience than people realise,” O’Malley-James told Gizmodo. “Especially with these kinds of flares, changing the atmosphere in that way is not going to make the planet completely uninhabitable. It might be bad for certain kinds of life, but it might be irrelevant for other kinds.”

So while it might not be ideal for astronauts to take a stroll on the beaches of the TRAPPIST-1 planets, something could be there — we’re just going to have to look a little harder for it. I, for one, want to believe.

[Arxiv]