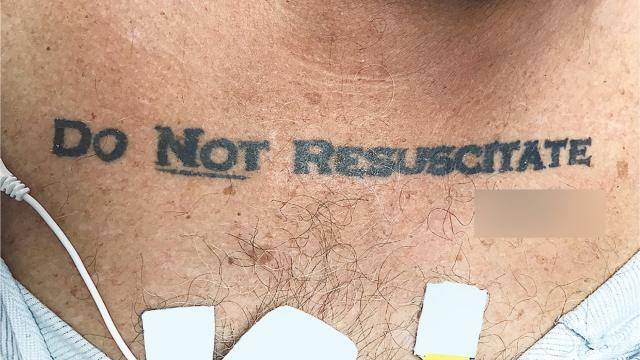

When an unresponsive patient arrived at a Florida hospital ER, the medical staff was taken aback upon discovering the words “DO NOT RESUSCITATE” tattooed onto the man’s chest – with the word “NOT” underlined and with his signature beneath it. Confused and alarmed, the medical staff chose to ignore the apparent DNR request – but not without alerting the hospital’s ethics team, who had a different take on the matter.

Image: NEJM/University of Miami

As described in a New England Journal of Medicine case report, the unnamed 70-year-old man was brought to the ER by paramedics in an unconscious state, and with an elevated blood alcohol level. The patient had a history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (a type of lung disease), diabetes, and an irregular heart rate. His condition began to deteriorate several hours after being admitted, and dramatic medical interventions were needed to keep the patient alive.

But with the “DO NOT RESUSCITATE” tattoo glaring back at them, the ICU team was suddenly confronted with a serious dilemma. The patient arrived at the hospital without ID, the medical staff was unable to contact next of kin, and efforts to revive or communicate with the patient were futile. The medical staff had no way of knowing if the tattoo was representative of the man’s true end-of-life wishes, so they decided to play it safe and ignore it.

“We initially decided not to honour the tattoo, invoking the principle of not choosing an irreversible path when faced with uncertainty,” wrote the authors of the case study. “This decision left us conflicted owing to the patient’s extraordinary effort to make his presumed advance directive known; therefore, an ethics consultation was requested.”

But there was more to it than just the medical ethics. Gregory Holt, the lead author of the new case study, said the biggest question in his mind was the legal aspect of whether or not it was acceptable. “Florida has stringent rules on this,” he told Gizmodo.

While the DNR tattoo may seem extreme, the request to not be resuscitated during end-of-life care is most certainly not. Roughly 80 per cent of US Medicare patients say “they wish to avoid hospitalisation and intensive care during the terminal phase of illness“. Revealingly, a 2014 survey showed that the vast majority of physicians would prefer to skip high-intensity interventions for themselves. Of the 1081 doctors polled, over 88 per cent opted for do-not-resuscitate status. Indeed, measures to keep a patient alive are often invasive, painful and costly. DNRs, which hospital staff refer to as “no-codes”, are an explicit request to forego high-intensity interventions such as CPR, electric shock and intubation tubes. More implicitly, it’s a request to not be hooked up to a machine.

Typically, DNRs are formal, notarised documents that a patient gives to their doctor and family members. Tattoos are a highly unorthodox – but arguably direct – means of conveying one’s end-of-life wishes. That said, this patient’s tattoo presented some undeniable complications for the hospital staff. Is a tattoo a legal document? Was it a regretful thing the patient did while he was drunk or high? Did he get the tattoo, but later change his opinion? On this last point, a prior case does exist in which a patient’s DNR tattoo did not reflect their wishes (as the authors wrote in this 2012 report: “…he did not think anyone would take his tattoo seriously…”).

In this most recent NEJM case, the ICU team did its best to keep the patient alive as the ethics team mulled over the situation, administering antibiotics, vasopressors (to reduce low blood pressure), intravenous fluid resuscitation, and other measures.

“After reviewing the patient’s case, the ethics consultants advised us to honour the patient’s DNR tattoo,” Holt told Gizmodo. “They suggested that it was most reasonable to infer that the tattoo expressed an authentic preference, that what might be seen as caution could also be seen as standing on ceremony [that is, adherence to medical tradition and norms], and that the law is sometimes not nimble enough to support patient-centred care and respect for patients’ best interests.”

Accordingly, the ICU team wrote up a DNR, and the patient died later that evening without having undergone any emergency DNR measures. Before he died, however, the hospital’s social work department discovered the patient’s Florida Department of Health “out-of-hospital” DNR order, which was consistent with the tattoo.

But as the authors of the new report point out, the whole incident “produced more confusion than clarity”, saying that, despite how hard it can be for patients to make their end-of-life wishes known, “this case report neither supports nor opposes the use of tattoos to express end-of-life wishes when the person is incapacitated.”

Kerry Bowman, a bioethicist at the University of Toronto, agrees that this incident was challenging.

“Advanced directives of any kind do not override most recent expressed capable wish,” Bowman told Gizmodo. “In other words, [the patient] may have changed his mind and there may be no way of knowing. Tattoo regret is not rare. [The ICU team’s] defence is erring on the side of life.”

At the same time, however, Bowman is sympathetic to the patient, saying the tattoo may be an expression of how often patients’ wishes are somehow overlooked and the system takes over. “My position would be if someone went to the great length of having DNR tattooed with a signature, it indicates a strong and clear wish,” he told Gizmodo.

Melissa Garrido, an Associate Professor at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in NYC, shares this sentiment, saying that even when a DNR order has been entered into a medical record, it is not always readily accessible in a health crisis. “A standardised tattoo may be a readily accessible method for communicating a strongly held care preference,” she told Gizmodo.