A vaccine for the most commonly reported sexually transmitted infection in the U.S. — the bacterial disease chlamydia — is now a substantial step closer to reality. On Tuesday, researchers reported that two of their vaccine candidates were found to be safe in a phase 1 clinical trial of 35 women. Though the trial wasn’t meant to prove their effectiveness, the vaccines also seemed to provoke an immune response to the bacteria in all volunteers.

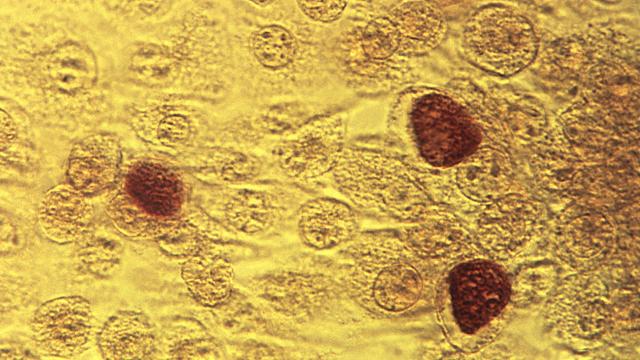

Chlamydia trachomatis, or just chlamydia, is thought to have caused at least 127 million new infections in 2016 alone, according to the World Health Organisation, a toll second only to those caused by the parasite trichomoniasis. In the U.S., it caused nearly 3 million new infections in 2017, according to the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention.

People with chlamydia often don’t know they have it, since many don’t experience any symptoms. But it can cause painful or bloody urination as well as genital discharge. If left untreated, it can lead to more serious complications like pelvic inflammatory disease, arthritis and even infertility. Carriers are also more susceptible to catching other STIs, including HIV.

Chlamydia remains almost always treatable with antibiotics. But antibiotic resistance is looming on the horizon for it and other common STIs, including gonorrhoea. So a vaccine would be invaluable and especially timely. Rates of chlamydia and STIs in general in the U.S. have steadily increased and hit a record high in 2017.

The two vaccine candidates, developed by researchers from the UK and Denmark, are based on the genetically engineered version of a major protein found on the surface of the bacteria. They differ in the other ingredients used to boost a person’s immune response to the vaccine, known as adjuvants.

In the trial, the team dosed 30 healthy women living in the UK with one or the other vaccine (split equally), and another five women with placebo. Over a period of four months, the women were dosed three times with a shot of the vaccine or placebo, then in the final month, they instead took the treatment twice through a nasal spray. By the end of the trial, 32 women had taken all five doses, though data from all the women was included in the final results.

A nasal spray vaccine for chlamydia, some scientists have theorised, could better train the immune system against it, mostly because the bacteria invades areas of the body that are covered in mucus, like our throats and genitals.

According to the team’s findings, published in the Lancet on Tuesday, there were no serious side-effects from either the shot or nasal spray. Vaccine takers were more likely to report irritation at the site of the shot than those who took a placebo, but they didn’t report more side effects from the nasal spray compared to the shot.

Regardless of the vaccine taken, the women had an immune response to chlamydia, based on tests of their blood as well as mucus samples taken from the vagina. But one of the vaccines was packaged with an experimental type of adjuvant developed by the researchers, called CAF01. Their earlier research had suggested CAF01 could improve the effectiveness of their chlamydia vaccine (as well as for vaccines for other diseases, including tuberculosis). And in this trial, the CAF01 chlamydia vaccine seemed to create a faster and more consistent immune response in volunteers.

”The vaccine showed the exact immune response we had hoped for and which we have seen in our animal tests,” said senior study Frank Follmann, director of the department of Infectious Disease Immunology at Statens Serum Institute in Denmark, in a statement from the institute. “The most important result is that we have seen protective antibodies against Chlamydia in the genital tracts.”

The team has worked on developing a vaccine for 15 years. But with these encouraging results, they hope to speed things along.

“Research shows that the combination of antibodies and T cells does protect against Chlamydia, but, of course, we have to test the vaccine in larger and more long-termed clinical trials to see if it protects against infection. Given the results at hand, we have accelerated our further clinical trials,” said Follmann.