The famous 3.2-million-year-old Lucy specimen has captivated scientists since it was discovered in 1974. Lucy was a member of the species Australopithecus afarensis, which walked upright and likely used tools. New scans of the inside of Australopithecus skulls reveal these extinct hominins had surprisingly ape-like brains that developed more like human brains.

Our brains take on a distinctive structure that differentiates them from the brains of non-human apes, and they take a long time to develop to maturity. Scientists have debated when during our evolution these traits developed: Did they take on their human-like organisation during the age of Australopithecus or during the evolution of later hominins? A new study seems to go against previous claims, showing that Lucy’s brain would have been quite ape-like—and yet, it also demonstrates human-like patterns in the way it develops.

“What’s really intriguing, though, is that even though the brain looks much like an ape brain, it has a human-like feature—that it grows for a long period of time,” said study author Philipp Gunz, biological anthropologist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. “Which is really intriguing, because it suggests that some of the unique modern features with regards to their long childhood learning and plasticity of the brain may have deep evolutionary roots already present in Australopithecus afarensis.”

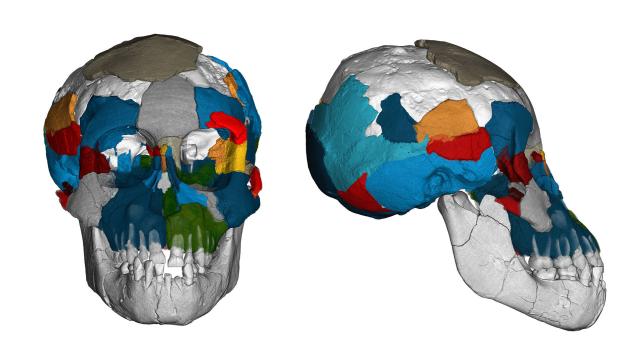

The team analysed two well-preserved Australopithecus afarensis infant specimens and six adults, including the famous Lucy fossil, using conventional CT scanning and CT scanning from the high-energy light produced at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility, a particle accelerator in France. By scanning the interior of the skull, it’s as if they’re creating a cast but using light instead of moulding material. They used virtual reconstruction techniques to correct how any damage to the skulls may have impacted the cast, which allowed them to generated high-resolution images of what the surface of the Australopithecine brains looked like.

Most notably, the scans revealed a feature previously undetected in Australopithecine brains: the lunate sulcus. This is a fissure in the folds of the brain found farther forward in chimps than in humans and would not typically be found in a cast of the interior of a human skull. The “unambiguous” detection of the feature in one of the infant Australopithecus skulls, as well as other folds, demonstrates that the overall surface of the brain looked a lot more like an ape brain than a human brain. The team did not find any evidence that the Australopithecus brain had begun reorganising itself into a more human-like layout or even size, according to the paper published today in Science Advances.

The researchers followed the cast analysis with a study of how the young specimens’ brains developed. Past research has demonstrated that tooth development can be used to model a specimen’s age at death, and in this case, the two Australopithecus children were probably around two and half years old when they died. They compared the estimated volume of the inner part of the cranium of the children and the adults in order to generate a trajectory of brain growth. They calculated that Australopithecus had already evolved a longer brain development period—more human-like than chimp-like in its timeframe.

“We all have a tendency to look at evolution on a continuum,” Jeremy DeSilva, associate professor of anthropology at Dartmouth who reviewed the study, told Gizmodo. But “this idea of everything evolving in lockstep is shattered by a paper like this. It shows that, like everything else in human evolution, we evolved in more of a mosaic, modular kind of fashion, where aspects of our anatomy evolved at different rates.”

In other words, the evolution from ape to human didn’t work linearly. Our pre-human ancestors may have taken on certain human-like features while simultaneously retaining distinctly ape-like ones. DeSilva explained that, waist-down, Australopithecus looked markedly human, but above the waist, they maintained more of an ape-like appearance.

Comparing the skull fossils and the pelvis fossils suggests that Australopithecus would have required help giving birth as humans do, which would further imply a social lifestyle, DeSilva said.

Though the study includes a large number of fossil specimens, there’s always the wish for more, especially given how little data anthropologists have to work with, Gunz explained to Gizmodo. More fossils could help confirm that these evolutionary patterns could be extended to the species as a whole and weren’t just peculiarities of the few individuals that scientists have excavated.

Still, this paper confirms that evolution doesn’t work in the cut-and-dry way you might imagine based on a clichéd image.