For a while now, I had been looking for an angle to tell the story of Rene Dreyfus, the Jewish racer driving for plucky little Delahaye who took on Germany’s Silver Arrow Grand Prix aces as the shadow of Nazism fell across Europe. Luckily for all of you, author Neal Bascomb’s is here and he tells Dreyfus’s story better than I ever could.

Faster traces Dreyfus’s ascendance in European auto racing, which coincided with the rise of Fascism in Germany and Italy, then (as now) the two powers in that very same sport. Bascomb’s book gives readers an attempt to understand those two narratives as being closely intertwined, with the political environment serving as both a damper on and motivation for Dreyfus’s successes on the track. Bascomb does his best to use prose to describe the on-track action, and he really does capture it rather well. But his skill certainly shines through as he leads readers through Dreyfus’s life off the track as well as the unignorable political context that creeps up on Dreyfus and the reader alike as the book goes on.

Dreyfus, born in 1905 to a secular Jewish family in Nice, began is his career racing for Bugatti in the 1920s. He was a rising star in the new sport of car racing, sharing racetracks and an expansive International social scene with the likes of racers like Louis Chiron, Rudi Caracciola, Bernd Rosemeyer. It was the

But Dreyfus’s Jewish heritage put the sport loved at odds with him as the nationalistic undertones that had always been present in car racing took on new significance as the Fascist regimes in Italy and Germany sought to tie the pursuit of speed on the racetrack to their pursuit of power over their own populations and their neighbours as well.

These circumstances (and very recognisably Jewish last name) kept a successful racer and only nominally Jewish man like Dreyfus from getting a spot in the cockpits of world-beater Italian teams like Alfa Romeo and Maserati as well as the mighty German competition.

It was that expansive social scene, though fraught with the chaos of the changing political climate, that gave Dreyfus his chance to defeat the teams who aimed to conquer racing in the name of totalitarianism because it was how Dreyfus came to meet American heiress Lucy Schell. Schell, who really is the book’s second hero, cut her teeth racing Delahayes in the Monte Carlo rally. Impressed with her Delahaye’s performance in long-distance rallying, Schell turned her attention to the highest form of racing there is: the Grand Prix.

With the V12-powered Delahaye under Dreyfus’s control, the spirit of motorsport could live on unimpeded by totalitarianism. Even though Schell and Dreyfus themselves were not politically-minded, their effort to bring the fight to the Nazis on the track and sitting above it in the stands was a valiant attempt to wrest whatever was left of motorsport away from those who would mobilize it in the service of Nazism.

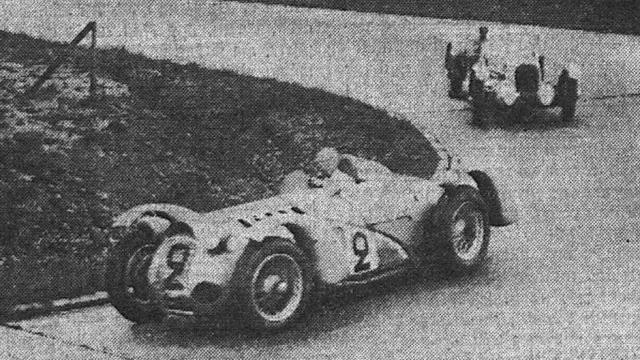

Bascomb structure’s his book’s climax around the spring of 1938, drawing two events, one to the east of Germany, the other to the west, into conversation with one another to great effect. The two events were the Pau Grand Prix, held on April 10th, and the Anschluss, or the absorption Austria into the Third Reich, which had occurred just a month before. It was at Pau that Dreyfus would finally defeat his German and Italian rivals in the legendary Delahaye 145, a moment of tremendous pride for Delahaye, France, Lucy Schell, and Dreyfus most of all. But the events happening off the track were unavoidable. Dreyfus’s victory for Delahaye was but a drop in the bucket compared with the mobilisation of Germany towards war.

Regrettably, this is where Bascomb’s book falls a little short. Of course, it’s hard to beat the triumph at Pau as a narrative climax, but I was interested to learn more about Dreyfus’s life after the war had shaken Grand Prix racing apart. Dreyfus went on to join the US Army during the war, fighting on the battlefield after already facing German aces years before on the track. After that, he became a restauranteur, feeding celebrities and racing drivers at his New York restaurant. Between all that he managed to race intermittently, and even had a podium finish Sebring in 1955.

As for Schell and Delahaye, the story isn’t much longer than what Bascomb includes, unfortunately. Schell passed away not long after the war in 1952 and Delahaye was absorbed into the labyrinth of French defence contractors through a merger with Hotchkiss in 1954. Though their stories don’t go much farther, it’s a delight to read Bascomb’s account of their efforts in the ‘30s to build tracing culture at odds with the German model. It’s where Bascomb’s writing shines and where his efforts to plumb the depths of archives and papers for the little details really pays off.

Bascomb’s book is probably most important not simply because it gives us an opportunity to read a Miracle-On-Ice-style story of a plucky underdog defeating an opponent backed by the industrial might of an empire, but rather because it speaks important truths about the intersection of motorsport and national politics at a moment where we need to examine that exact intersection in our own time.

Though tracks are dormant right now because of the global pandemic, motorsport remains a venue for political posturing even today. Countries like Azerbaijan and Saudi Arabia, facing scrutiny from within and without for human rights violations of all stripes, have placed significant resources behind building their national statures in the world of racing, not just in Formula One but in

Rally and Formula E as well. Here at home, the Daytona 500 was turned into a veritable election rally for Donald Trump just a few months ago. Politics didn’t leave the racetrack once World War II was over, and we need to reckon with that fact.

Of course, it’s important to differentiate the way that German nationalism and Nazi ideology influenced the participation of Auto Union and Mercedes Benz in 1930s Grand Prix racing and states investing in the hosting of races as a tool to endear people abroad and deflect international scorn. But nonetheless, the specter of politics hangs heavy over racing as it always has. Perhaps now more than any time since the ‘30s, and that’s why it’s important to read Dreyfus’s story.

He and his team overcame the political and engineering might of an ascendant Nazi Germany and came out victorious. At least until the politics caught up. If we really care about motorsport, our society, and our friends, we’ll look at Dreyfus not merely as a racer who beat the odds, but as a symbol for racing unimpeded by political considerations, where the universalism of the pursuit of speed and skill doesn’t brake for anyone, fascists least of all.

‘Faster’ by Neal Bascomb was released on March 17th. It is available on Booktopia here though it’s worth asking your local bookseller if they have it in stock. They need your business.