Earlier this week, the U.S. reached another sad milestone in the covid-19 pandemic, with the country now reporting over 2 million confirmed cases of the viral disease, along with at least 115,000 deaths.

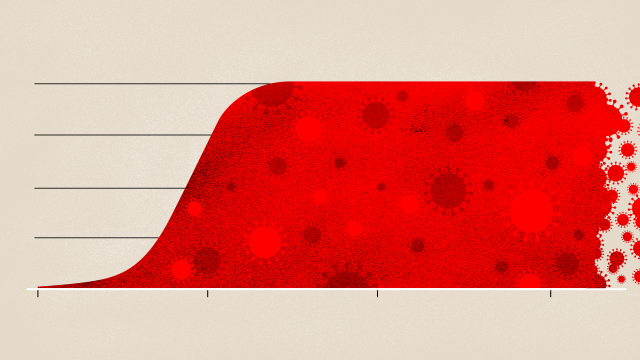

As the Northern Hemisphere summer gets into full swing and much of the country lifts its restrictions on distancing, though, it’s important to keep in mind that we may not see an immediate and dreaded second wave, as many onlookers fear, at least not everywhere in the U.S. Rather, the country could be staring at an agonising plateau for the foreseeable future, where outbreaks pop up in some places and slowly fade away in others, ultimately leaving the country at a still-awful baseline of new cases and deaths every day. But even if things don’t get better in the U.S., that doesn’t mean it should give up on containing the virus as much as possible in local cities or towns or that there aren’t steps every person can take to keep themselves and their loved ones safe.

For weeks now, a familiar chorus has rung out on social media in response to news articles reporting on, for example, an infected partygoer who visited Missouri’s Lake of the Ozarks during the crowded Memorial Day weekend there: Just wait two weeks for the huge wave of new cases to show up (a reference to the typical incubation period of the virus). Yet, when you check back on these specific stories, that hasn’t happened.

So far, no covid-19 cases have been linked to the Memorial Day crowds who were infamously photographed bunched together and not wearing masks at the Ozarks, even when accounting for the one known person who developed symptoms while visiting there. A week before these parties, two hairstylists in Missouri were also found to have contracted the virus and may have potentially exposed 140 of their customers to it. But again, health officials said this week that no further suspected cases were reported among these customers in the weeks since (a caveat here is that only 46 people were actually tested for the virus, all negative).

And despite the mass protests that began in states including New York in response to the police killing of George Floyd on May 25 — the earliest demonstrations now more than two weeks ago — New York continues to report declining cases, hospitalisations, and deaths. Hennepin County, Minnesota, where Floyd was killed and where the protests started, has experienced fewer daily cases in the two weeks since, as have other areas where large protests have been held.

There are several reasons that might explain why these mass gatherings haven’t yet led to an explosive outbreak — reasons that similarly lower the odds of an imminent second wave happening all across the country.

For one, research is starting to suggest that most infected people don’t spread the virus to others at all. Instead, so-called super-spreading events might account for the bulk of cases in an outbreak or cluster, where only one person or a few people transmit the virus to many others. Just because someone is a super-spreader doesn’t mean that they’re inherently more contagious than others, though; instead, it might come down to outside variables. The same person who silently works in a cubicle all day might not infect anyone there, but they could spread the virus easily to the rest of their choir at night while singing, for example. So the chance of any single infected person causing a huge outbreak is relatively low in isolation and probably depends heavily on where and how that person interacts with others.

Another consideration is the weather. Very few cases have been linked to the outdoors, likely because sunlight and wind seem to have a modest but real effect on reducing transmission. Masks, too, seem to play a big role in lowering transmission risk. All of the people involved in the potential Missouri hair salon outbreak were wearing masks while giving and receiving haircuts, for instance.

Of course, these isolated non-events don’t take away from the fact that the U.S. is very much in the grips of a nationwide epidemic. Even as the daily death toll is slowly dropping from its peak in April, the country is still reporting around 20,000 new cases a day — a number that hasn’t changed much since mid-May.

Some of this plateau can be attributed to increased testing, which may be picking up milder cases that won’t lead to hospitalisations and deaths. There are certainly states where the situation has gotten much better, and fewer new cases are being found than before, such as New York and most of the Northeast. But there are several states, including Texas, Arizona, and North Carolina, where hospitalisations are rising. These states, perhaps not coincidentally, are some of the first to have lifted lockdowns and restrictions on distancing.

It’s absolutely plausible that these or any future outbreaks later on in the year could worsen to the point where much of the U.S. ends up where New York was in April, when hospitals in hard-hit areas were stretched thin and hundreds of residents died every day from covid-19. But it’s also possible that we’ll continue to see an ebb and flow of hotspots in some parts of the country and never a full-on second wave — a patchwork pandemic, as the Atlantic’s Ed Yong has coined it.

These hotspots may emerge in part because of a mismanaged response by states opening up too early without enough precautions, like a sturdy test-and-trace program to stop outbreaks before they start. But they might be also tamped down or prevented by people being compassionate enough to wear masks when in crowded places; businesses and customers adopting consistent rules on keeping physical distance even once they open up; and employers who allow people to keep working from home or to stay home when they feel sick.

We are nowhere near post-pandemic, as some have rushed to call this time period. An average 800 people in the U.S. are still dying every day; countless others will be left with lingering health problems or ruinous medical bills. By the fall, the virus may have killed 200,000 Americans, almost certainly making it deadlier this year than any other cause of death besides unrelated heart attacks and cancer.

But we’re not helpless against the coronavirus. We know how to lower our risk of catching and spreading it; we’re getting better at understanding its biology; and hopefully, we’ll have better tools soon to help the most severe cases or prevent new ones. We can protect each other by keeping a distance whenever possible, wearing masks when it’s not possible, getting tested if we suspect we’ve been exposed, and isolating ourselves if we get infected.

Pandemics happen because people are inevitably drawn to one another. But it’s that same collective spirit that’s also made most of us willing to sacrifice these last few months of being connected physically — sacrifices that may have already saved millions of lives worldwide. Things haven’t been and won’t be easy for a while longer, but we can get through it together.