Henry isn’t your average dog. When his little black nose wiggles toward a smell, it’s not usually a snack or treat. Hell, it’s not usually a smell he even likes. Henry, a 4-year-old black and white English springer spaniel, has been trained to find hedgehogs. He’s damn good at it, too ” despite finding them awfully stinky. In the UK, scientists are beginning to turn to conservation detection dogs to help them conduct their research, including on hedgehogs.

While Henry is among the first dogs to contribute to UK research, conservation dogs have been an integral part of studies elsewhere. In Argentina, for instance, conservation dogs have helped scientists map a wildlife corridor through sniffing out the scat of big cats. In South Africa, these brilliant dogs have been used to monitor cheetah populations. Now, this research method is finally taking off in the UK.

Louise Wilson, Henry’s mama and managing director of Conservation K9 Consultancy, has been leading these efforts. She started her career training dogs to detect explosives and drugs, but she’s since reoriented her skills. She doesn’t have to worry anymore about sending her dogs off to Afghanistan or Iraq, never to see them again. Her 11 conservation dogs live with her, in fact.

“I train all my wildlife detection dogs like I did my explosive dogs,” Wilson told Gizmodo. “I would never send an explosive dog out unless I was 100% sure it could do the job at hand.”

In the case of wildlife detection dogs, the job at hand is sniffing out hedgehogs, as well as bats and bird carcasses at windmill sites in partnership with academics. Henry can do all of the above. That wasn’t always the case, though. By the time Wilson took him in at eight months old, Henry had been through five homes. She suspects that was due to his load of energy. He would start fights with her other dogs. He’d bark and growl. Wilson believes Henry had been punished early on in his life and gave him a few months to grow comfortable and trust her before she began any training.

“He needed time,” Wilson told Gizmodo. “The thing is, he is so clever. I probably never met a springer spaniel as clever as him.”

Now, he’s a pro.

Wildlife detection dogs need some natural impulse control ” especially if they’ll be looking for live animals. Some scientists have been hesitant to use conservation dogs, Wilson said, because they’re scared they may harm the animal they’re studying. If a critter is endangered or suffering population decline, you can see how that would be a problem.

That’s why much of Henry’s work so far hasn’t yet been in the formal surveying of hedgehogs. It’s been to establish in the literature that dogs are, in fact, capable of this work. The goal here is to show scientists ” who are driven by research and data ” that conservation dogs are worth investing in.

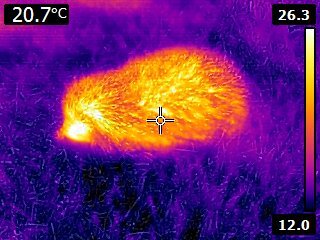

In the case of hedgehogs, they’re facing increased habitat loss from building projects and lawn maintenance. Developers often kill them without even meaning to. In the last decade, a quarter of the population has been lost in the UK. In an effort to step up conservation, scientists have taken to weighing, sexing, and checking them for injuries or wounds, before fitting them with a radio tracker. This information gives the researchers a better idea of the health of the individual and also that of the local population. Research into hedgehogs is ongoing, including work that’s under peer review. Once they formally tease out what’s causing decline, conservationists can more effectively target their recovery strategies.

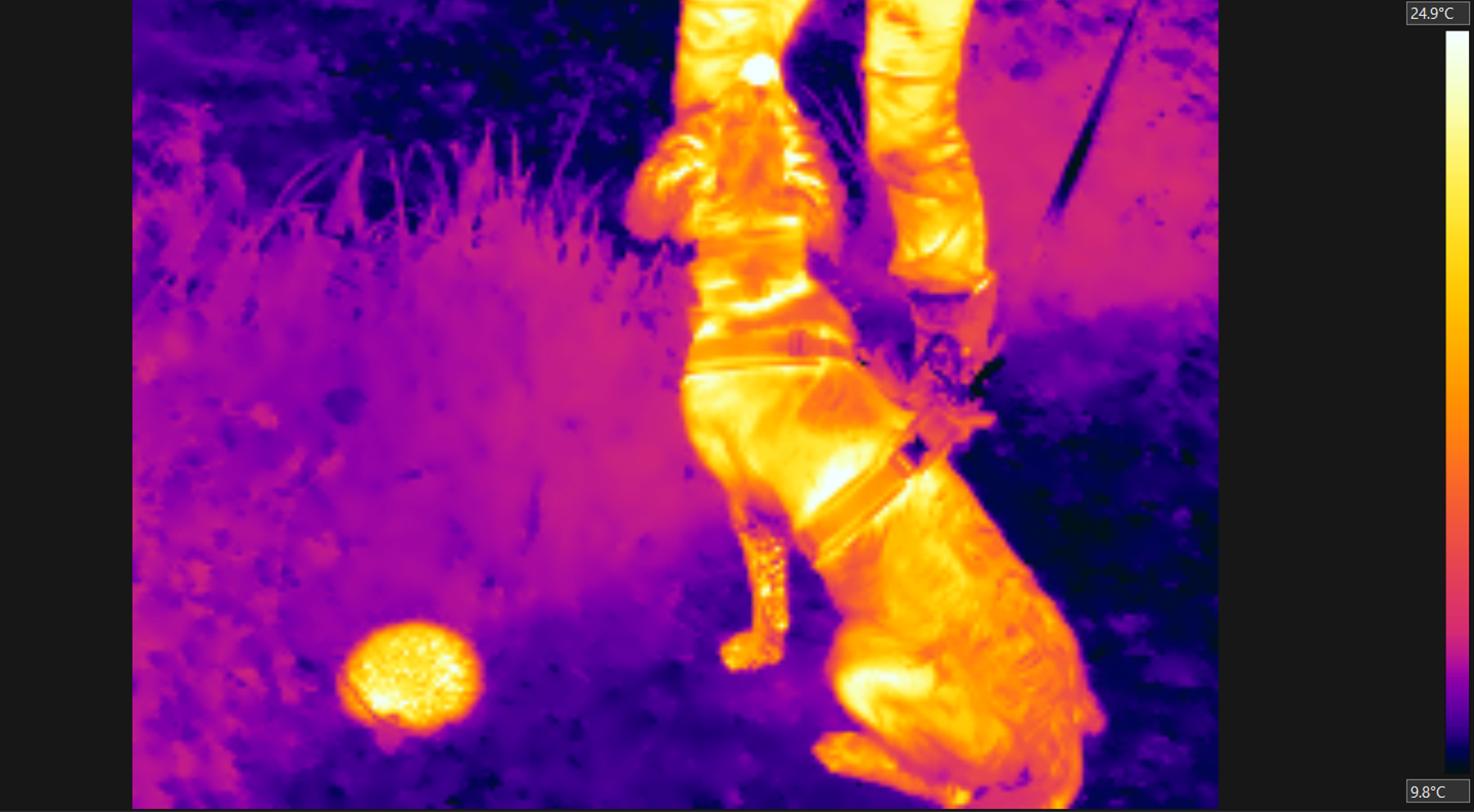

Historically, this fieldwork has occurred at night because that’s when hedgehogs are active and typically easiest for humans to find. A big part of Henry’s initial work was joining Lucy Bearman-Brown, a senior lecturer at Hartpury University, to go hedgehog searching at night. These missions would start around 11 p.m. and end around 3 a.m. The whole time, Henry rarely grew tired.

Both he and Bearman-Brown would look for hedgehogs to see how effective dogs could be compared to the traditional thermal camera methods researchers use. In some instances, Henry was just as good as the thermal camera. In others, such as searching in areas with denser vegetation, he had a clear advantage.

Combining dogs with other tools like thermal cameras could make researchers’ lives a lot easier ” and funnier. Â Henry will charge off into the night if he catches a whiff of a hedgehog, even if Bearman-Brown and Wilson are packing up for the day. He’s hardworking like that.

“It can be really useful having him on the team”¨ to find those ones that are out of sight,” Bearman-Brown told Earther. “If you can’t see it with your eyes, you probably wouldn’t be able to detect it with the thermal camera if it’s in long-grass vegetation. Thermal cameras generally only work in low-level vegetation, but Henry can find them all over the place.”

Working with Henry was Bearman-Brown’s first time going into the field alongside a very good boy. She’s excited to dive into the next piece of their research in September, which will examine how effective Henry can be at finding hedgehogs during the day when they’re nesting. Researchers haven’t typically conducted surveys during the day because hedgehogs are harder to find, but this is when the animals are most vulnerable to losing their habitat ” and life ” to construction or landscaping. Hedgehogs can travel 1 to 2 miles in a night but usually return to the same nest. Studying them while they’re staying put can further help researchers figure out how to protect them.

Preliminary missions already indicate that Henry will find this next task quite easy. Whether a hedgehog is buried under in a pile of leaves or hiding in a rabbit hole, his nose is on it. Like I said, he’s not your average dog.