With the tagline “Fight fire with fire,” the dragon apocalypse blockbuster Reign of Fire crashed and burned at the box-office in the summer of 2002. Once it hit home entertainment, the metamorphosis from flop to beloved cult film was almost instantaneous. Over the next two decades of cable reruns, the movie rose from the ashes to a loyal fandom. Gizmodo spoke to the director and screenwriter about its surprise legacy and how this wild idea became an even wilder film.

Set in a dystopian London besieged by dragons, Reign Of Fire debuted in third place on its opening weekend, behind Men In Black II and Road To Perdition. By the end of its theatrical run, it barely scraped back its $82 million budget (grossing $112 million internationally), which is an interesting figure when you consider its stars — Matthew McConaughey, Christian Bale, Gerard Butler — were all on their way to A-List status. “I don’t think you can afford to put those three guys in the same movie right now,” director Rob Bowman reflected.

“One regards Reign Of Fire with awe,” wrote Roger Ebert in 2002. “Incredulity is our companion, and it is twofold: we cannot believe what happens in the movie, and we cannot believe that the movie was made.” He added that it “makes no sense on its own terms, let alone ours.” Variety’s Joe Leydon noted that it had “an uncommonly satisfying mix of medieval fantasy, high-tech military action and Mad Max-style misadventure” while the New York Times’s Elvis Mitchell added it had “a jamming B-picture buzz,” and was “loads of fun” — “the kind of swift filmmaking and high spirits that have been missing from movies for a while.”

Those reviews recognised something late Hollywood producer Richard “Dick” Zanuck also saw. Having won a Best Picture Academy Award for Driving Miss Daisy — a win that hasn’t aged well in hindsight — Zanuck was best known for producing classics like The Sound Of Music, The Verdict, and Jaws.

“The original script was a spec that was written by these guys who I don’t think had ever written anything before, like, these Wisconsin guys,” recalled screenwriter Matthew Greenberg. “I remember reading about it when it sold and thinking ‘Ah! Why didn’t I think of this? This is great!’ It sort of had to be written by people who weren’t in the film industry, because if you told anybody the pitch was ‘dragon apocalypse’ they’d be like ‘get the fuck out of my office!’” Those ‘Wisconsin guys’ Zanuck took a gamble on were Gregg Chabot and Kevin Peterka, who had never had anything made before Reign Of Fire and have never had anything made since, only adding to the mystique.

Then in his sixties, Zanuck didn’t care about what their previous credits were or weren’t: he cared about what was on the page and what he saw was a merging of medieval and military. More importantly, he felt it was something he had never seen before. “It wasn’t only dragons,” said Greenberg. “It was dragons and modern-day in this sort of fucked up setting. In Hollywood, it’s very interesting because you’re dealing with vast amounts of money and everybody’s scared: terror and anxiety and envy are the three major emotions that you pass through… Where Dick was brilliant was he understood the balance between risk and safety, he always knew you could play it safe and you might get lucky, but when he saw something that really spoke to him… From our first pitch he got it, he understood where at least I was coming from, and with his son Dean — who was also a producer and extremely smart — they were able to guide it through the initial stages of development.”

Then a “baby writer,” Greenberg was considered the guy you got to punch up a script and make it shootable — which is exactly what he was hired to do for Chabot and Peterka’s script. Yet unlike his last two projects with Dimension — Mimic and Halloween H20 — he had fought to get on Reign Of Fire, not just as a fan of the early draft but as someone who had a background in it “academically” after being a medieval studies major in college.

The biggest issue, however, was money. “The first script I read would have cost $US300 ($411) million and that was not gonna happen,” said Bowman, who was eventually hired to come on board as director. “It was too big and too expensive, but I knew how to par it down and what to focus on and I didn’t think anyone else was gonna make it. I didn’t feel — probably arrogantly — that anyone else knew how to make it except me. I guess that’s the armour I have to put on to say ‘I’m the only one who can get this story to the audience.’ I knew what the elements were, what the recipe was, that would make it worthwhile: tanks and castles, soldiers and dragons. I hadn’t seen that one before.”

At the time, he was coming off the back of a big hit with The X-Files movie after directing and producing dozens of episodes of the show. It too was high-concept genre fare, but on a $US66 ($90) million budget, Bowman had been able to craft something that was faithful to the feverish fandom and a $US189.2 ($259) million hit at the box-office. It put him in the sights of many a Hollywood exec, including Zanuck. “The first notable thing I recall was after I’d read the script — an early draft — being invited to Richard Zanuck’s office, which of course I would run to,” says Bowman. “Waiting there with all the movie posters was a surreal moment, just knowing that I was going to meet this guy considering his legacy.”

The initial projected budget to get the movie made was in part what had seen Reign Of Fire bounce around from Spyglass to Fox to Touchstone and Disney, but it was Bowman’s “distilled” version that eventually got the greenlight. And, said Greenberg, his ability to ground the wild concept in reality. “I’ll tell ya something, there was a picture that director Rob Bowman showed me early on that blew me away… It was a dragon, but also he had a massive B-52 bomber that had just gone through combat, so it was fucked up in different places and you could see all the damage. I thought ‘Well, that’s pretty genius.’”

The bare bones of the plot has a young boy witness the death of his mother after the London tunnelling project she’s working on digs too deep, unearthing a long slumbering species of bloodthirsty dragons. Fast forward 20 years and that boy is now a man, Quinn (Christian Bale), who catches us up on everything that has happened since: the end of the world, basically. It was dragons who wiped out the dinosaurs, their ash causing the ice age and now the eventual downfall of man as city after city falls to swarms of “millions.” He’s holed up in what they believe is one of the last strongholds of humanity, inside an English castle where he and his best mate Creedy (Gerard Butler) try to keep the next generation alive and hopeful: the pair perform staged versions of Star Wars and The Lion King to keep the kids entertained in what is one of the more genuinely sweet moments in the story.

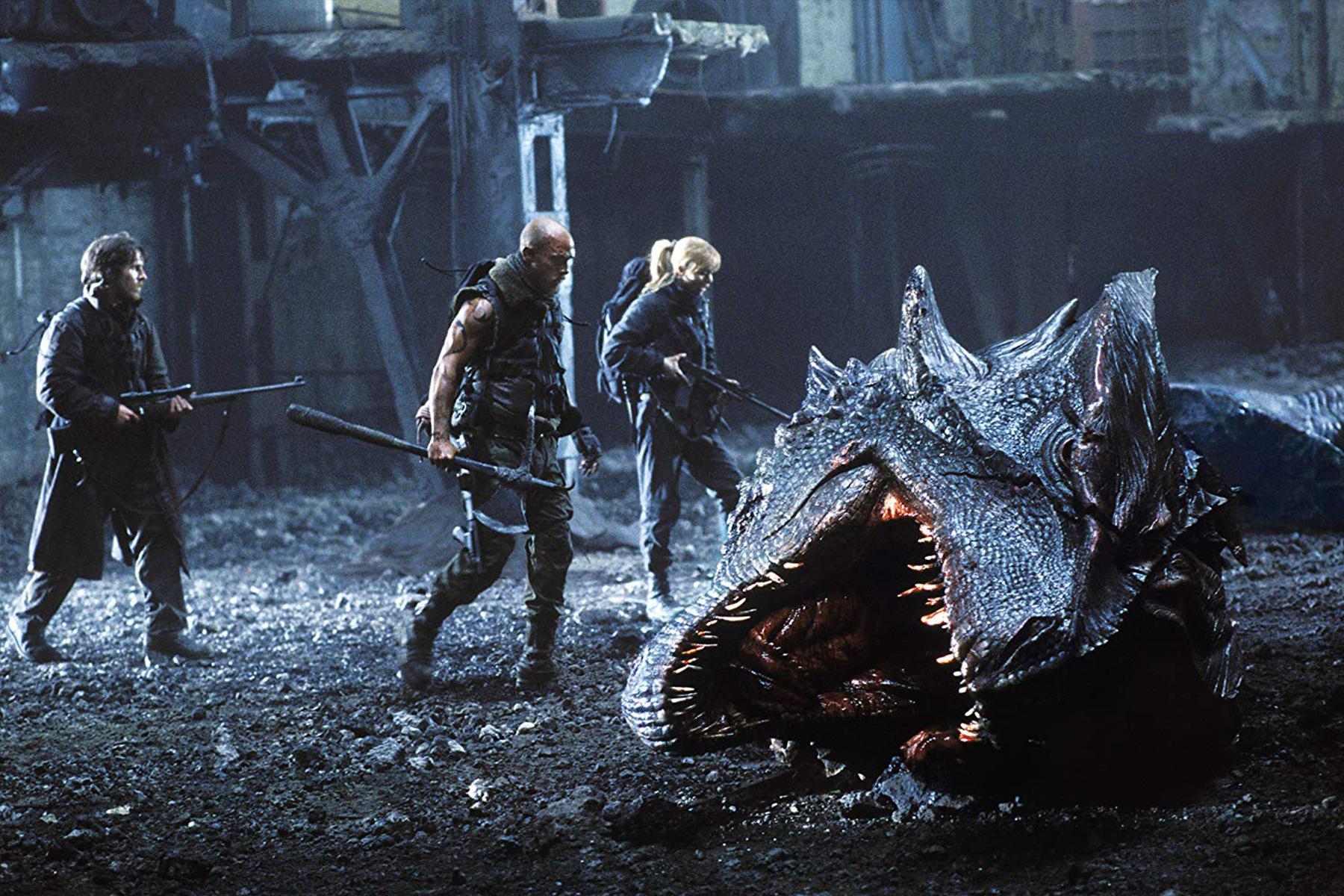

Their uneasy peace is disturbed, however, with the arrival of Americans — of course — who come in tanks and helicopters and dirt-smeared singlets under the leadership of Matthew McConaughey’s dragon slayer Denton Van Zan (a Hall Of Famer for ridiculous cinematic bad-arse names). It’s a B-movie blockbuster, if such a thing can exist, with straight-faced performances from Oscar-winners like Bale and McConaughey paired with things like Arcangels: soldiers with a 17-second lifespan who yeet themselves out of helicopters and directly at the dragons terrorizing them.

“I know in the earlier drafts there was a little more digital technology in the weaponry,” said Bowman. “I think there was laser sighting and RPGs. The problem with anything you can use at a distance is it doesn’t require much courage from the character. The version I came up with was more hand-to-hand, which is impossible really and no different than tangling with a shark or handling a tiger. It’s like ‘What did you expect the outcome to be? You’re going to be dead dead dead.” Greenberg added: “The idea — they’re not referred to as such in the movie — but in the script they were firemen. It was this whole idea of firemen as these latter-day knights going up against obviously this mythic threat. I had some friends who were all ‘That’s stupid, that’s so dumb’ and I was like ‘Fuck you!’ I mean, friendships were lost over this.”

Friendships were also formed over it, namely between the core trio of Bale, McConaughey, and Butler who were all just a few years out from their seminal roles: Bale hadn’t yet become Batman and Butler was still to scream “This! Is! Sparta!” in 300. That’s not to say they weren’t known entities, but Reign Of Fire came in between two of McConaughey’s biggest rom-com hits — The Wedding Planner and How To Lose A Guy In 10 Days — and a full decade before the McConaissance began in earnest. Yet few people were more dedicated.

“That dude committed, man,” Greenberg chuckled. “The director told me stories how he would get calls from Matthew — you know, when we were still in pre-production — and Matthew would talk to him not as Matthew McConaughey but as Van Zan.” Bowman confirmed he definitely got phone calls from McConaughey in character as the dragon slayer, but it was perhaps less mythologized than people remember: “He’s a funny guy, he’s got a great sense of humour.” He was also “tenacious and ferocious in his commitment to playing that role” Bowman said. “Matthew basically told me that I wasn’t allowed to make this movie without him.”

For his part, it was the “primal” nature of the character that drew McConaughey to Van Zan. “It did seem wild,” he said on the Reign Of Fire press tour in 2002. “Go be a man of action, go be a bad-arse, go take care of business, a man working from necessity, not luxury, a man who doesn’t talk about things but does ‘em.” It was also the Academy Award-winner’s idea to don Polynesian-inspired dragon tattoos, something that meant hours of extra time in the make-up chair each day but was supposed to be somewhat of a tribute to the famous New Zealand rugby union team the All Blacks.

Butler’s casting was the beginning of a true bromance between him and Bowman, with the director affectionately calling him “Gerry.” “We had a meeting at Disney and I walked into the room and fell in love with this guy instantly,” said Bowman, who met with just Butler for the part before offering him the role. It was Bale, he said, who was “the real journey” and a hard sell for the studio who felt he “doesn’t bring much box-office pull.” In fact, it was very nearly a showdown between two of the most iconic muscle men of the ‘80s: Arnie and Sly.

“The producers had asked me if I would consider Stallone and Schwarzenegger,” Bowman recalled. “I said the problem with that is I know who’s gonna be alive at the end of the movie and I know what’s gonna happen to the dragon. I kind of torpedo the dragon’s menace and threat from the beginning because I have that impenetrable, perpetually victorious actor character if it’s Arnold or Sly. Those guys have such a huge screen presence. I’m already asking the audience to say ‘OK, there’s fake dragons in this movie as the villain.’ I couldn’t ask them to do anything else.”

Bale was his pick for the leading man, given he was “a very strong, soulful person who didn’t bring much baggage” and the genius of that choice shines in the smaller moments, those when he interacts with the children and leads them in reciting their daily prayer, if you will. “What do we do when we wake up?” he asked. “Keep two eyes on the sky,” the tiny survivors reply. “What do we do when we sleep?” “Keep one eye on the sky.” While a no-brainer now, at the time it wasn’t just the studio Bowman had to convince about Bale — it was Bale himself. “I flew over to Berlin where he was filming, met him in the restaurant at the Four Seasons, and what I remember was he was very pleasant and fine mannered. But he looked at me and held the script up with one hand and said something to the effect of ‘What are we gonna do about this?’ And I was like ‘Christian, I’m reading the same script you’re reading, I know what it is and I’m gonna fix it.’ And he said ‘OK, tell me what it is?’ I told him what I wanted to do with it and that to me, it was really a story about the strength of the human spirit.”

Bowman’s hard sell worked, along with the promise to ground his dragons with as much “ultra-realism” as possible — a key element that fans still love and dissect today, the medieval-meets-military aesthetic. “There was just really great potential,” said Bale in an interview at the time. “It could have gone hideously wrong — like any movie could — but I thought this one could go even more hideously wrong than most when, you know, you’re dealing with dragons.” It was only “after speaking with Rob” that Bale thought he could do it. “Christian at that meeting in Berlin made me promise and when he looks at you and he means it, that’s a hard look,” said Bowman. Bale was on-board, so too Butler and McConaughey, and after securing a tax break in Ireland the production headed there for 90 days of principal photography.

In Greenberg’s words “there was nothing easy or normal” about that shoot, not just the fact that the blackened wasteland he’d described in his script was now going to be physically created in one of the lushest places on earth. “They asked me to take that stuff out of the later drafts and I was like ‘Why?’ and this guy said to me ‘well, it turns out that Ireland is really green,’” laughs Greenberg. “I go ‘You realise it’s called the Emerald Isle, right? And that’s not because of the mineral content.” There was also an outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease, which meant the bodies of sheep on nearby farms were being burned in “these spires of fire and smoke that was just wafting on to the set.” Despite there being some 30,000 castles still standing in Ireland, Reign Of Fire’s big set piece had to be built from scratch. “Apparently people would be driving along — tourists — and they’d see this castle and go ‘Oh, this castle isn’t on the map, let’s go up and see,’” said Greenberg. “They’d get shooed away by the crew.”

The events of the film are set in a dystopian future that takes place in the year 2020. In our version of 2020, we’re more familiar with the idea of the end of the world than the filmmakers could have guessed at the time but perhaps interestingly, Reign Of Fire has never been more popular than it is right now. In part, that’s thanks to Game Of Thrones: the technology used to create the dragons in the series naturally drew a visual comparison to Reign Of Fire, which pioneered how to make giant, flying reptiles look believable rather than…well, you know, Dragonheart.

“The genius of it was no one had done a truly authentic, ultra-realistic dragon [movie] or set it in an environment that seems real,” said Bowman, who wanted his beasties as “Natural Geographic authentic” as possible. “I probably made it 10 or 12 years too early because as the artists said ‘Everyone started ripping off our dragons’ and I was like ‘Yeah, well, at least that means we’re still relevant.”

Reign Of Fire spent a year in post-production once the Ireland shoot wrapped and given what Greenberg considered a small budget — that $US60 ($82) million figure down from a projected $US300 ($411) million — he called it a technical achievement. “If we’d made this movie today, we could have done everything because we have the technology,” he said. “But back then, we had stuff, but we didn’t have nearly the access we do now. In the end, it got made. It’s not fucking 120 pages being used as a doorstop somewhere, which is pretty cool.”

When Reign Of Fire did debut in cinemas with a whimper before hitting home entertainment, it wasn’t as poorly received as you might think a movie about Bale, Butler, and McConaughey fighting dragons might be. The box-office had underwhelmed, but critics seemed to appreciate the endeavour. “Look, I’ve worked on some bad movies,” said Greenberg. “I mean, truly, truly awful movies — Children Of The Corn III! With Reign Of Fire, there was a sense that even though it didn’t make money, it was a worthy attempt… They respect people who have the balls to make this shit and I think after the smoke cleared a little bit, there was a sense that this journey was worth it.”

The impact it had with the general public outside of Hollywood, however, was where the filmmakers first started to notice an interesting response. It was in 2003 at a barbecue store that — in a casual conversation with the checkout clerk — Greenberg revealed he had written the movie. “He yells ‘YOU WROTE REIGN OF FIRE?! Oh my God, man!’ and he pulls me aside, brings me to his partner and tells him ‘Dude, this guy wrote Reign Of Fire!’ His friend looks at me and I can tell he fucking hated that movie and he hated me. When you work on a project, in a weird way, you kinda want that: you want a passionate response whether it’s positive or negative… My dad saw the movie in 2002 and goes ‘I saw it, what the fuck?’ and now every time it’s on cable, he calls me all excited. He has become the biggest fan of it.”

For Bowman too — who went on to direct Elektra afterward and found continued success in television with Castle and The Rookie — Reign Of Fire is a subject that comes up often, more often than he ever expected. “The compliments don’t stop coming to this day, [so I] must have done something right,” said Bowman. “I don’t read reviews, but I made the best movie I could make — everyone who worked on it did — and as they say in sports, I left it all on the field… Entertainment is a business, but it’s supposed to be an art also. I’m not saying it’s the Mona Lisa.”

There was a planned Reign Of Fire sequel according to internet forums at the time, but it was something neither Bowman or Greenberg heard anything about. A so-so video game adaptation and rumoured television series that never eventuated saw the end of a dragon multiverse. Yet fans have kept it very much alive, not just through social media where seemingly obscure films suddenly have a burgeoning online fandom, but through subReddits that theorise possible prequels and custom scale replicas of Van Zan that still sell for hundreds, sometimes thousands of dollars. That may seem surprising to some, but after nearly 30 years in the business, it’s not a shock to Greenberg.

“Of all the movies I’ve worked on, that has been the one that people keep talking about,” he said. “What the director was able to do, what the actors were able to do, everything, they did touch on this mythic sense that can last through time and I don’t mean to sound grandiose. I think the reason movies or really any work of art lasts is because human beings are all tuning forks and occasionally something comes along, pings, and makes you ring even years later.”

Maria Lewis is a best-selling author, screenwriter, journalist and host of the six-part limited podcast series Josie & The Podcats. She can be found on Twitter @MovieMazz.