Scientists have mapped the entire nuclear genome of a saber-toothed cat species known as Homotherium latidens, also called the scimitar-toothed cat. The resulting DNA analysis suggests these Pleistocene predators were fearsome pack hunters capable of running for long distances as they chased their prey to exhaustion.

Smilodon, with its impossibly long fangs, is probably the most famous saber-toothed cat, but new research published today in Current Biology suggests another saber-toothed cat, a species known as Homotherium latidens, is equally worthy of our attention.

Oh, in case you’re wondering, “saber-toothed cats” is a kind of colloquial catch-all term used to describe extinct predatory felids with long canines that protruded from their mouths even when their jaws were closed. The more technical term for this group is Machairodontinae, a now-extinct subfamily of Felidae. And no, we don’t call them “saber-toothed tigers” anymore, because they weren’t actually tigers.

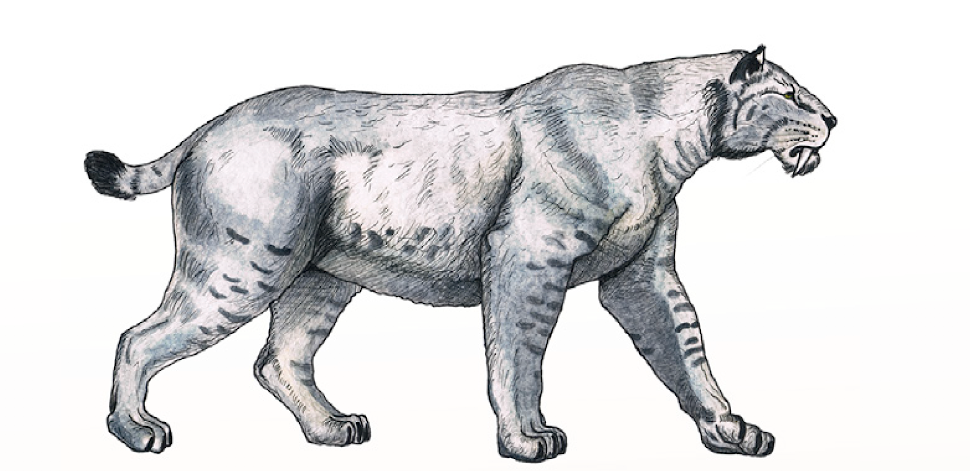

Homotherium, also known as the scimitar-toothed cat, may not have sprouted maxillary canines on the scale of Smilodon, but these predators had a lot going for them. They were built for long-distance running and were more slender than Smilodon and modern lions. Homotherium’s limb proportions are reminiscent of those seen on modern hyenas, as they featured longer forelimbs relative to their hindlimbs, according to Michael Westbury, the lead author of the new study and a geneticist at the University of Copenhagen.

Sitting comfortably atop the food web, Homotherium preyed on large Pleistocene herd animals, such as giant ground sloths and mammoths. They used their long incisors and lower canines for puncturing and gripping, as well as picking up and relocating dead prey.

These traits and behaviours were primarily inferred from fossil evidence, but many questions about Homotherium remained unanswered, such as the specific genetic adaptations that allowed them to thrive and survive and whether these animals interbred with other saber-toothed cat species.

To learn more about scimitar-toothed cats, Westbury and his colleagues recovered and analysed DNA from a Homotherium latidens specimen found in Canada’s Yukon Territory. The specimen, pulled from frozen sediment, was too old for radiocarbon dating, so it’s at least 47,500 years old, according to the new study. The researchers mapped its entire nuclear genome — a first for a saber-toothed cat — and compared it to those of modern cats, like lions and tigers.

“The quality of this data allowed us to do a lot of interesting analyses that are normally limited to high-quality genomes from living species,” explained Westbury in an email, saying he was surprised to obtain such good quality DNA from a specimen so old.

The scientists found no less than 31 genes in Homotherium that were subject to positive selection. Of note, the genetic makeup of their nervous system points to complex social behaviours, which meshes nicely with our understanding of this animal being a pack hunter. Scimitar-toothed cats also had good daytime vision, which means they were a diurnal species that likely hunted during daylight hours. They had special genetic adaptations for strong bones and robust cardiovascular and respiratory systems.

Taken together, the “novel adaptations in these genes may have enabled sustained running necessary for hunting in more open habitats and the pursuit of prey until their point of exhaustion,” wrote the authors in the study.

“Our results support previous work attempting to correlate specific morphological and anatomical characteristics of H. latidens to its lifestyle,” said Westbury.

Another key finding of the study is that scimitar-toothed cats were genetically diverse, at least compared to modern cat species. They only bred amongst themselves and were highly populated, as far as big cats go. For scientists, this is new information.

“We find that the Homotherium may have been relatively abundant compared to living large cat species. Homotherium is relatively scarce in the fossil record, leading researchers to believe they were not so abundant,” said Westbury. “However, by looking into the genetic differences between the mother and father of our individual, we found they were quite different compared to what we see in other cat species, suggesting a large population size.”

Importantly, this DNA analysis was limited to a lone individual, so future work should seek to corroborate these findings with more genetic evidence.

The researchers also found that Homotherium and modern cats diverged from a common ancestor a very long time ago — around 22.5 million years ago. By comparison, humans and gibbons split apart from a common ancestor some 15 million to 20 million years ago. It should be no surprise, then, that such vast differences appear in saber-toothed cats compared to modern lions, with the former appearing like some kind of bear-hyena-lion hybrid.

The new DNA study affirms findings from the fossil record and reveals some things about Homotherium we didn’t know before. Life was good for these animals for millions of years, with large herd animals fuelling their voracious lifestyles. It all came to a close, however, with the gradual loss of large prey and the end of the last ice age.