Prehistoric teeth found over 100 years ago are some of the best evidence yet for hybridised communities of Neanderthals and modern humans.

We know that Neanderthals and early modern humans interbred — our DNA tells us so — but fossil evidence in this regard is surprisingly lacking. Hence the importance of the new research paper, published today in the Journal of Human Evolution.

The evidence consists of prehistoric teeth recovered from the La Cotte de St. Brelade cave site in Jersey, an island located in the English Channel, in 1910 and 1911. The teeth, belonging to two individuals, exhibit characteristics consistent with interbreeding, pointing to the presence of hybridised populations.

There is now “considerable DNA evidence that interbreeding happened, both from fossils and modern genomes,” Chris Stringer, a co-author of the new study and an archaeologist at the Natural History Museum in London, explained in an email. Indeed, most people with recent ancestry from outside of Africa have around 2% Neanderthal DNA in their genomes. That said, archaeologists “still don’t know the exact circumstances, nor how much this was a blending absorption of the Neanderthals into expanding modern human populations,” added Stringer.

That communities of mixed ancestry existed during the Middle Paleolithic, some 48,000 years ago, is potential evidence that “extinction” is probably not the best word to describe the fate of Neanderthals. Instead, these hominins, and their DNA, were absorbed by the increasingly dominant newcomers to Europe: modern humans (Homo sapiens).

The cave at La Cotte de St. Brelade was occupied for well over 200,000 years. Excavations made during the early 20th century resulted in the discovery of over 20,000 stone tools, as well as bones from mammoths and woolly rhinos. Exceptionally low sea levels during the last ice age made it possible for groups to migrate to the Channel Islands.

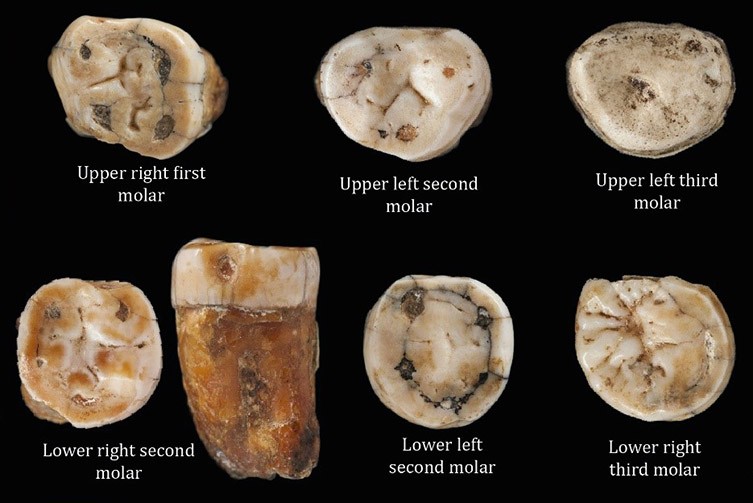

The teeth, 13 of them, were found in a single location on a ledge behind a hearth. The fossils were kept as a single set and assumed to belong to a lone Neanderthal individual. Stringer, along with colleagues from the UCL Institute of Archaeology, the University of Kent, and other institutions, borrowed the teeth from the Jersey Museum & Art Gallery to conduct an analysis with modern methods and tools, including CT scans.

Of the 13 teeth, one went missing over the years, and another was found to belong to some kind of animal. The remaining 11 teeth, it was determined, belonged not to one but two individuals. Importantly, the teeth exhibited signs of hybridisation.

“We find the same unusual combinations of Neanderthal and modern human traits in the teeth of both identified Neanderthal individuals,” said Stringer. “We consider this the strongest direct evidence yet found in fossils, although we don’t yet have DNA evidence to back this up. In summary, the tooth roots look very Neanderthal, whereas the neck and crowns of the teeth look much more like those of modern humans.”

The recency of the mixed ancestry could not be determined, but Stinger speculates it happened within the prior few generations. The ultimate test will be a DNA analysis of the teeth, which the team plans on doing in the future.

“The only other explanation I can think of for this combination of traits of the two species is this is a population that evolved the highly unusual combination of traits in isolation,” he said. “However at this time, because of the lower sea levels of the last ice age, Jersey was definitely connected to neighbouring France, so that level of long-term isolation is unlikely.”

Recent dating of sediments at the site suggests the teeth are approximately 48,000 years old, which places them roughly 8,000 years prior to the extinction of the Neanderthals. These archaic humans emerged some 400,000 years ago, and their remains have been found all across Eurasia. The finds at La Cotte de St. Brelade, therefore, are from a late stage of the species. Indeed, this was a critical time in human history, as early modern humans were spreading across Europe and breeding with Neanderthals.

[referenced id=”1137653″ url=”https://gizmodo.com.au/2018/11/neanderthals-werent-the-violent-brutes-we-thought-new-research-finds/” thumb=”https://gizmodo.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/15/zsch9murpxz1qughu3cz.png” title=”Neanderthals Weren’t The Violent Brutes We Thought, New Research Finds” excerpt=”The stereotype of a typical Neanderthal life is that it was extraordinarily difficult, violent, and traumatic. But a comparative analysis of the remains left behind by Neanderthals and contemporaneous humans is finally overturning this unwarranted assumption.”]

The reasons for Neanderthal extinction remain unclear, but going theories include violent conflict with modern humans, disease, climate change (and an inability to adapt), and, as mentioned, interbreeding. That Neanderthals were absorbed into our species seems an increasingly plausible explanation.

“Of course, there might be many different scenarios across the Neanderthal world which led to their disappearance, from local extinction to absorption into expanding populations of Homo sapiens,” Matthew Pope, a co-author of the study and an archaeologist at the UCL Institute of Archaeology, explained in an email. “Here at La Cotte, we might get a chance to look at one scenario up close, through further detailed excavation and scientific analysis.”

To which he added: “Who knows, given how broadly Neanderthal these teeth look, maybe it was part of the Homo sapien population that was being absorbed at this point in time?”