Virologist and medical researcher Jonas Salk developed a successful polio vaccine that was approved in 1955, helping the world all but eradicate the disease.

When the late journalist Edward Murrow asked Salk who owned that vaccine’s patent, he famously responded, “Could you patent the sun?” It was in large part his commitment to keeping the jab’s recipe open-source that vaccines were produced globally and millions around the world were able to get it.

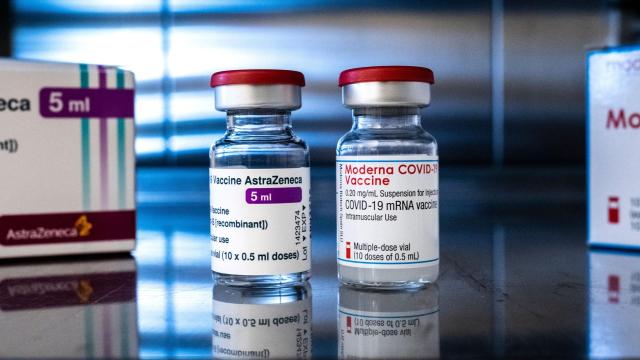

As the covid-19 health crisis unfolds, multinational pharmaceutical corporations like Moderna and Pfizer have taken a different approach. Their tight hold on the technology for their covid-19 vaccines has made them billions of dollars. While these strict intellectual property laws protections have allowed the rich to get even richer, they’ve put a damper on efforts to manufacture vaccines at scale. And with supply limited, the U.S. and other rich nations have engaged in bilateral negotiations with pharmaceutical corporations and hoarded all the doses they can, leaving poor nations in the dust.

The loss of life and suffering sparked by these strict patent protections are a major warning sign for our climate future. To avert environmental catastrophe, everyone needs access to clean energy. Intellectual property law could get in the way of that. And in the end, we could all suffer the consequences of a clean energy apartheid.

I have two family WhatsApp groups, one for family here in the U.S. and one mostly full of relatives who live in India. The latter feels like a portal into a different world. My U.S. family has been sharing second-dose selfies and questions asking if it’s cool to go to indoor restaurants. My family in the southern hemisphere are almost all sick. They’ve been swapping tips for how to cope with their fevers, sending out GoFundMe pages for others who have the coronavirus, and telling horror stories about how armed security guards are watching over oxygen tanks.

As they’re quick to note, these horrors are in part due to the failures of the failures of the Indian government. But they’re also due to the inaccessibility to vaccine recipes. Globally, half of the doses of covid-19 vaccines administered so far have gone to the richest 16% of the world’s population. In the U.S., nearly 30% of the population is vaccinated. Schools and bars and gyms are beginning to open up, and many of us are reuniting with friends we haven’t seen in a year. Meanwhile, India is experiencing the worst covid surge the world has seen yet. On Monday, it recorded 352,991 cases, breaking the record for the number of new cases seen in any nation in a single day.

Loosening patent restrictions could immediately help speed production around the world and ease the crisis. Yet despite the clear and present suffering, Bill Gates — a key player in COVAX, a global private-public partnership that allows market mechanisms to dictate access to vaccination technology — has argued companies should hang onto their intellectual property, claiming it would lead to unsafe vaccines. Big Pharma trade groups have made similar arguments, and multinational corporations in the Global North have maintained a tight grip on their patent protections even as public health experts warn India could face a half-billion cases of covid-19 as the public health system collapses.

“This is business as usual for the neoliberal global economy,” Tobita Chow, the director of the Justice Is Global project for the progressive organisation People’s Action, said. “It’s designed to maximise the profits of multinational corporations in the U.S. and other developed countries, and insofar as the general public benefits, the benefits are concentrated in the U.S. and other Global North countries. Excluding millions or even billions of people to maximise the profits that corporations can gain from intellectual property is how this system has always worked.”

At its general council meeting next week, the World Trade Organisation has the opportunity to help staunch the spread of covid-19 by waiving some protections on covid-19 vaccines developed by Moderna and Pfizer under the Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights Agreement. More than 100 nations, including India, have urged it to do. The Biden administration is reportedly considering endorsing this move, though then again, it’s been reportedly “considering” it for months.

This isn’t just something World Trade Organisation negotiators should do out of the goodness of their hearts — though it absolutely is that, assuming they have hearts. Failing to do so could result in variants that bypass vaccines, which could harm those lucky enough to have gotten the shot and send the world economy back into a tailspin.

“As the pandemic ravages the Global South, what are wealthy northern countries going to do? Just completely ban all contact with poorer countries? It won’t work,” said Basav Sen, climate justice project director at the Institute for Policy Studies. “It is extremely short-sighted to push this kind of logic of intellectual property and corporate profit over what is clearly a prominent threat for all of humanity.”

The same is true of clean energy patents. Like covid-19, carbon emissions don’t respect borders. If corporations’ strict intellectual property protections in the Global North and high price tags on green technologies prevent poor nations from decarbonizing, it will imperil us all. The worst effects will be seen in the southern hemisphere, but the U.S. and other wealthy countries aren’t immune to climate change. Just look at recent hurricane and wildfire seasons for the direct impacts as well as the knock-on effects of climate change such as the destabilization of Syria that caused widespread suffering and a wave of refugees.

Wealthy nations have the greatest capacity for researching and developing clean energy technologies — technologies that the whole world needs. But strict intellectual property laws could slow deployment and advances elsewhere.

“These intellectual property restrictions on technology make it more expensive for Global South countries to access these technologies and can also lock these countries out of creating clean energy industries themselves,” said Chow.

This also forces low-wealth nations to consider these exorbitant costs when making international climate pledges, which can disincentivize them from setting ambitious targets.

“These [are] countries which often know very clearly how climate change is a pressing problem,” said Chow. “They know they’re getting hit the hardest by contributing the least to carbon emissions. But they can’t afford to make those promises. They know it will cost them.”

Promoting the free transfer of technology isn’t a new idea. In fact, the 1992 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change included stipulations about technology transfer, calling on rich nations to share their developments with poorer ones. The 2015 Paris Agreement included similar language. But corporations have every incentive not to align themselves with these pledges. If we don’t confront these issues, the fight to curb the climate crisis could replicate the same inequalities that created it in the first place.

Of course, intellectual property agreements aren’t the only thing holding poor nations back from producing and deploying either covid-19 vaccines or solar panels. Even if protections are waived, access to essential technologies should also be made free, and rich nations should help invest in manufacturing capacity abroad.

“Just like the pandemic, the climate crisis is a global problem and needs a global solution,” Nafis Hasan, a postdoctoral researcher at Tufts University and board member of left-wing science advocacy organisation Science for the People, wrote in an email. “The Global North has a climate debt to pay to the South, and this can be done by free tech transfer.”

Again, this need not come from a sense of altruism from corporations. “This kind of thing could be set up in a way that is a win-win where we could have companies in more developed countries working on long-term investment in the Global South, and that can pay for them in the long run,” said Chow. “If you think longer-term, it could be a smart investment.”

In a just world, though, corporate profits wouldn’t even enter the picture when considering how to disperse potentially life-saving goods like medical vaccines or clean energy.

If the free transfer of essential technologies sounds like a radical impossibility, consider that Salk’s polio vaccination breakthrough came under 70 years ago. The flu vaccine, too, was developed without any intellectual property considerations.

“You have scientists all around the world tracking the yearly mutations of the flu virus. They all get together, they figure out what the next wave going to look like, they figure out the formula, and then everyone uses it everywhere to manufacture flu vaccines,” said Chow.

Conservatives often claim that intellectual property protections are essential to boost global technological innovation. But as Sen said, that’s simply ahistorical.

“If you look back before the history of colonialism and capitalism, we can remind ourselves that there were so many thousands of years of human history before that,” he said. “People evolved from hunter-gatherer societies to agrarian societies to building cities. And along the way, there were lots of inventions, and none of them were patented. Think of the people who domesticated wolves and turned them into dogs. Or the wheel. Did that need a patent? No.”