A group of archaeologists has found the oldest deliberate burial of a modern human ever discovered in Africa, dating back 78,300 years ago. The discovery sheds new light on the early origins of this ancient practice.

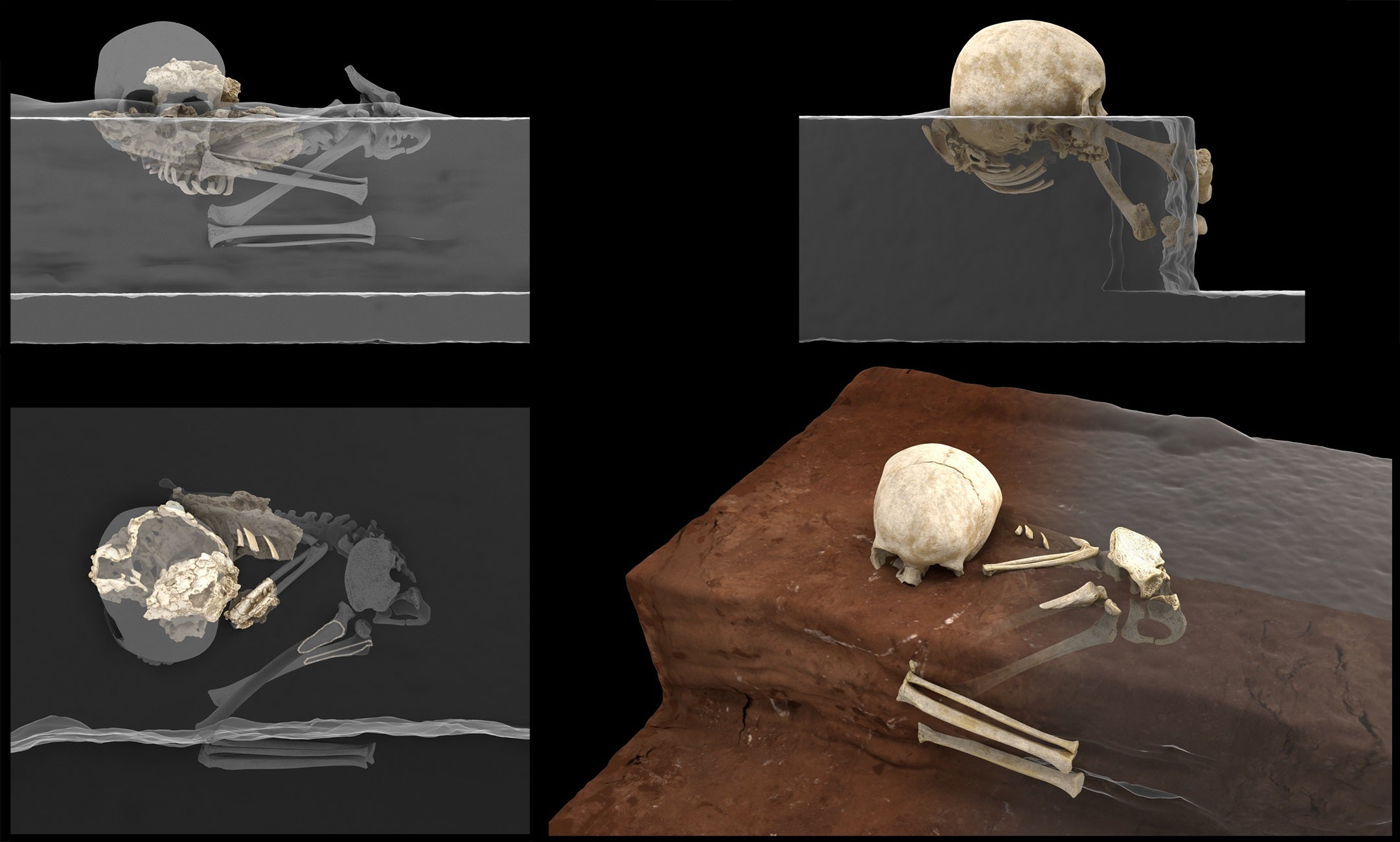

Tens of thousands of years ago, a toddler no older than three years old passed away in what is now Kenya. A shallow pit was deliberately dug out directly beneath the cave entrance in preparation for burial. The child, wrapped tightly in some kind of material, was placed carefully into the circular grave — the body placed on its side and with legs pulled up to the chest. Very tenderly, the child’s head was positioned atop a pillow, perhaps a bundle of grass or some other perishable material. The prehistoric funerary ritual ended with the body being covered by sediment sourced from inside the cave.

Such is the remarkable scene as described in a paper published on Wednesday in Nature. Led by archaeologist María Martinón-Torres from National Research Centre on Human Evolution (known by its Spanish acronym CENIEH) in Spain, the paper describes the remains of a young child found in the Panga ya Saidi cave near the Kenyan coast. Dated to 78,300 years ago, it’s now the earliest deliberate burial of a human to ever be discovered on the African continent.

“I think this is a very important find, and I agree that this is probably the oldest known burial in Africa,” Chris Stringer, an archaeologist at the Natural History Museum in London who wasn’t involved in the new research, said in an email.

Similarly aged burials in Africa, such as the intentional 74,000-year-old burial of an infant found at Border Cave in South Africa, and a 69,000-year-old burial of a child at Taramsa Hill in Egypt, are a bit younger and made complicated by tenuous dating. Importantly, older intentional burials have been found outside of Africa, including the 122,000-year-old Tabun C1 Neanderthal site in Israel, and the 90,000-year-old Skhūl site, also in Israel, involving the deliberate burial of modern humans (i.e. Homo sapiens).

The rare discovery at Panga ya Saidi is thus a big deal, as it firmly establishes the presence of this funerary practice during Africa’s Middle Stone Age, a period that ran from between 280,000 to 25,000 years ago.

That ancient humans, whether Neanderthals or modern humans, intentionally buried their dead is a well-established fact, and perhaps something we all take for granted. As humans, it’s something that we do. But it’s important to take a step back and process what this actually means. The practice of intentionally burying the dead is a behaviour that distinguishes us from virtually every other species. That’s not to say nonhuman animals don’t mourn their dead, or at least display behaviours consistent with grieving (good examples abound).

That said, intentional burials can be considered a major demarcation point in the cognitive, sociocultural, and technological development of a species, with links to social institutions, symbolic thought, and even a metaphysical belief structure (i.e. religion). Simply put, intentional burials represent a quantum leap in a species’ organizational complexity.

Archaeologists uncovered the first evidence of this child’s bones back in 2013, but it wasn’t until 2017 that they realised these bones were located in some sort of pit. Found roughly 10 feet (3 meters) below the current surface level of the cave, the bones were packed tightly together, requiring the team to use stabilizers and plaster to assist with the extraction.

“At this point, we weren’t sure what we had found,” Emmanuel Ndiema, a co-author of the study and an archaeologist at the National Museums of Kenya, said in a statement. “The bones were just too delicate to study in the field … [so] we had a find that we were pretty excited about — but it would be a while before we understood its importance.”

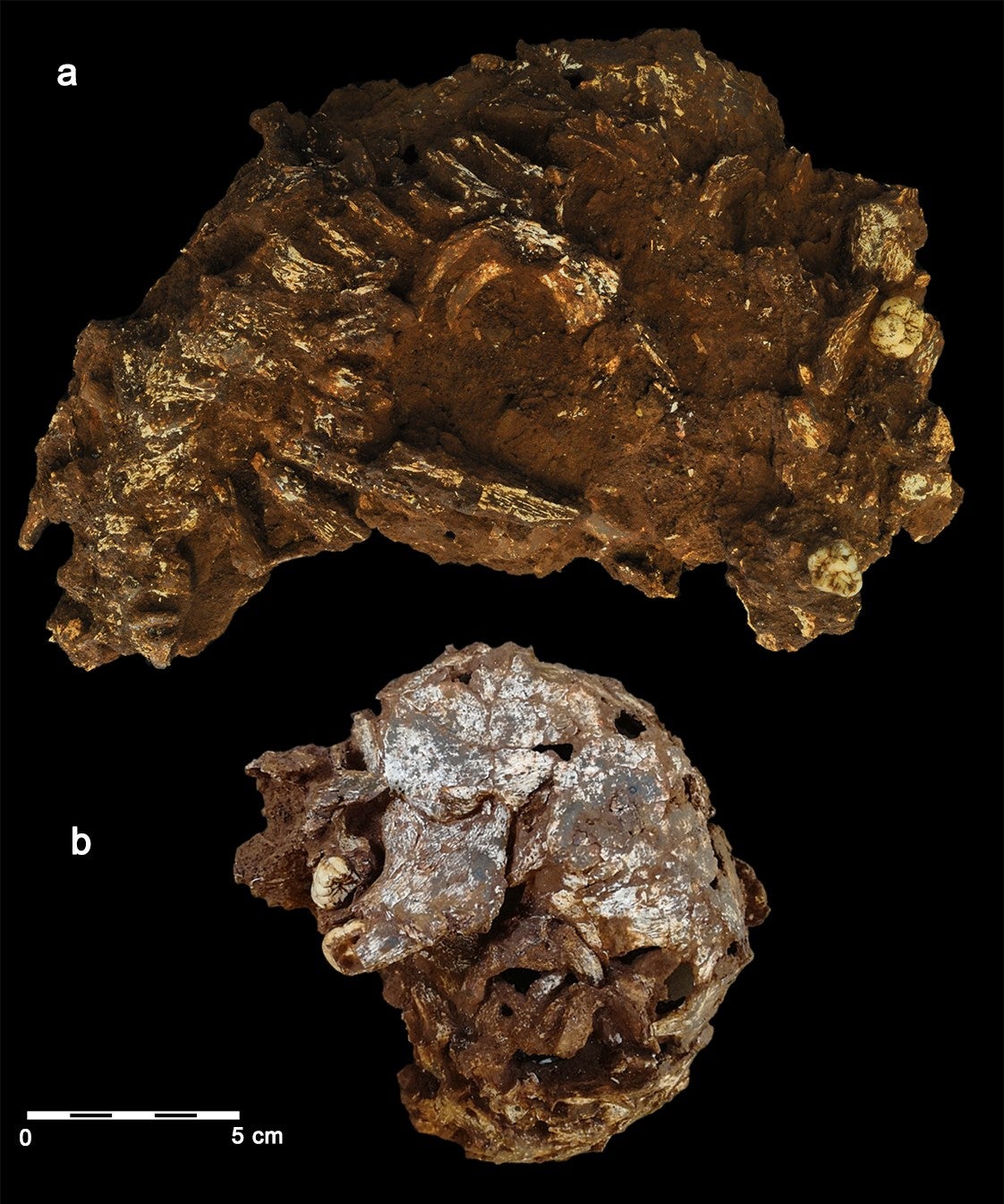

Caked in plaster, the partial skeleton was shipped to the National Museum in Nairobi for preliminary analysis, and then to CENIEH in Spain for further treatment and analysis. These investigations revealed a skull, teeth, and mandible containing some unerupted teeth. A dental analysis placed the age of the child, dubbed Mtoto (meaning “child” in Swahili), to between 2.5 to 3 years old at the time of death, while the size and shape of the teeth confirmed Mtoto as being a modern human.

“The articulation of the spine and the ribs was also astonishingly preserved, even conserving the curvature of the thorax cage, suggesting that it was an undisturbed burial and that the decomposition of the body took place right in the pit where the bones were found,” explained Martinón-Torres in the press release.

Indeed, all evidence pointed to a deliberate burial. The shallow grave, located directly beneath the overhang of the cave’s entrance, was intentionally excavated, and the child’s body was covered by sediment sourced from the cave floor. Microscopic analyses of the bones and surrounding soil suggest the body was covered by sediment immediately after death, with all decomposition happening within the pit. Using a technique called optically stimulated luminescence, the remains were dated to 78,300 years old, with a margin of error of 4,100 years.

This child could’ve been buried to prevent scavenging, but this seems unlikely. Had this been a concern, the child would’ve been buried far away from the cave. Other evidence, such as the careful positioning of the body, suggests the burial was done as part of a funerary ritual. As Martinón-Torres pointed out, the use of a pillow or some form of headrest is a potential indication that the “community may have undertaken some form of funerary rite.” Mtoto was also carefully wrapped in organic material (now fully decomposed), as evidenced by the rotated position of the child’s ribs. This was a carefully orchestrated burial, not something done haphazardly or out of sheer utility.

In an accompanying news and views article in Nature, archaeologist Louise Humphrey from the Centre for Human Evolution Research at the Natural History Museum in London who wasn’t involved in the new study had this to say about the discovery:

“The presence of symbolic aspects elevates treatment of the dead from mortuary behaviour to funerary behaviour. The burial reported by Martinón-Torres and colleagues reveals the care and effort taken to achieve a desired body position by supporting the child’s head and wrapping the upper body. This burial, together with a previous report of the burial of a child around 74,000 years ago, associated with a shell ornament in South Africa at Border Cave, suggests that a tradition of symbolically significant burials, at least for the very young, might have been culturally embedded in parts of Africa in the later part of the [Middle Stone Age of Africa].”

Stringer agreed, saying the Panga ya Saidi burial is “important for the circumstantial evidence of the complex treatment of the child’s body,” as Mtoto appears to have been covered or wrapped in some way, and given a headrest.

“More than anything, this find shows us how much evidence we are still lacking from many parts of Africa, either because of poor preservation of the skeletal material, or the lack of exploration for appropriate sites,” said Stringer. “I’m sure there is more extensive and older evidence of human burials to come from the Middle Stone Age of Africa.”

Which is a very good point. Modern humans have been around for 300,000 years, so it’s likely that intentional burials in Africa started long before 78,000 years ago. We just have to find them.

More: 9,000-year-old burial of female hunter upends beliefs about prehistoric gender roles.