A re-examination of fossils from central Australia has led to the discovery of a previously unknown species of crocodile. Now extinct, the giant reptile likely preyed on animals of equally formidable size.

The 8-million-year-old bones of multiple crocodiles, including an impressive skull, were found over 10 years ago at the Alcoota fossil site in central Australia, approximately 200 km from Alice Springs in the Northern Territory. This region, now parched, was once capable of supporting a population of large crocodiles, as it featured rushing rivers and fresh pools of water.

When paleontologists first encountered these bones, they rightly assigned them to an extinct genus of crocodile known as Baru. What they didn’t realise however, and as their thorough new investigation has revealed, they belong to an entirely unknown species of Baru crocodile. A scientific paper describing and naming the new species is currently in the works, and it should be published in early 2022, as Adam Yates, the senior curator of Earth Sciences at the Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory, explained in an email.

Modern crocodiles currently living in Australia belong to the genus Crocodylus, and they are believed to have arrived from Africa within the last few million years. Baru belong to an ancient group called Mekosuchinae, now extinct, which dates back to around 45 million years ago. An interesting aspect about the new fossils is that they were dated to approximately 8 million years ago, positioning them as among the most recent Baru crocodiles on the continent. The soon-to-be named species lived during the Late Miocene, which spanned 12 million to 5 million years ago.

A large skull found at Alcoota is the prize fossil, and it will be the holotype, or name-bearing, specimen. Dozens of other bones were found, including juveniles and adults. This “makes our new Baru species perhaps the best known of all Australian fossil crocodiles,” said Yates, who’s a co-investigator on the project. Comparative anatomy, along with modern phylogenetic techniques, allowed the team to place the new species within the family tree of crocodiles.

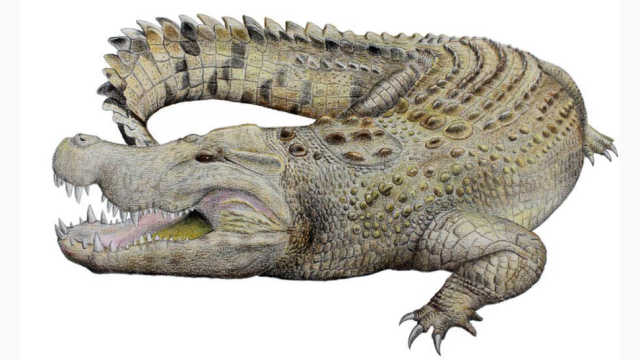

“Some of the distinguishing features are its extreme robusticity and relatively large teeth,” said Yates. “The large size of the teeth mean that they are more crowded in the jaws, and there are fewer of them than in the new species’ closest relatives.”

The largest bones suggest adults grew to around 4 to 4.5 metres in length. That’s a big croc, no doubt, but not record-breaking. That said, the robustness of its bones and the large size of its muscle attachments point to a “far heavier-bodied animal than a modern saltwater crocodile of equivalent length,” said Yates. Its exact weight could not be determined, but it likely weighed many hundreds of pounds. Importantly, these estimates were based on just 10 individuals; the “chances that we have a ‘record-breaker’ for the species among those 10 is slim, and it is entirely possible that the largest Baru matched the largest saltwater crocodile in size,” added Yates.

These creatures also featured thick, heavy, and deep jaws. Yates suspects these reptiles preyed upon large animals, including a large flightless bird called Dromornis stirtoni. Fossils of these birds, which stood upwards of 3 metres tall and weighed 650 kg, have previously been found in context with Baru crocodiles, suggesting they were prey animals for the reptiles.

The newly discovered species is important, as it could shed new light on the environmental conditions of central Australia during the Late Miocene, as well as why this species — and the entire genus — eventually went extinct.