A team of Korean researchers have made a membrane that can turn saltwater into freshwater in minutes. The membrane rejected 99.99% of salt over the course of one month of use, providing a promising glimpse of a new tool for mitigating the drinking water crisis.

Freshwater has become an increasingly precious resource. A major 2018 report warned that a quarter of the world’s population lives in areas that are under water stress. The climate crisis is worsening the situation by causing places that rely on snowpack for water to runoff earlier, an impact on display in California right now.

The new research published in the Journal for Membrane Science chronicles a unique way to desalinate water. The team designed a nanofiber membrane (a very good screen of extremely small things) which they say could turn seawater into drinking water in minutes.

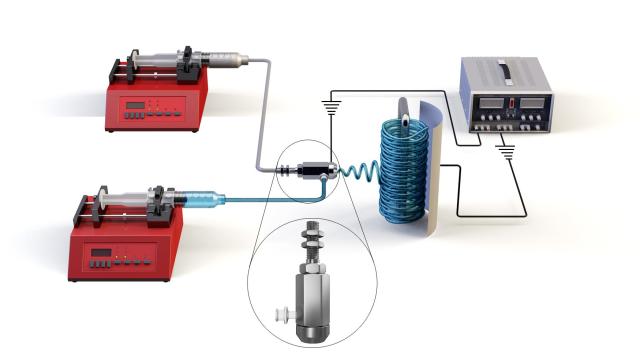

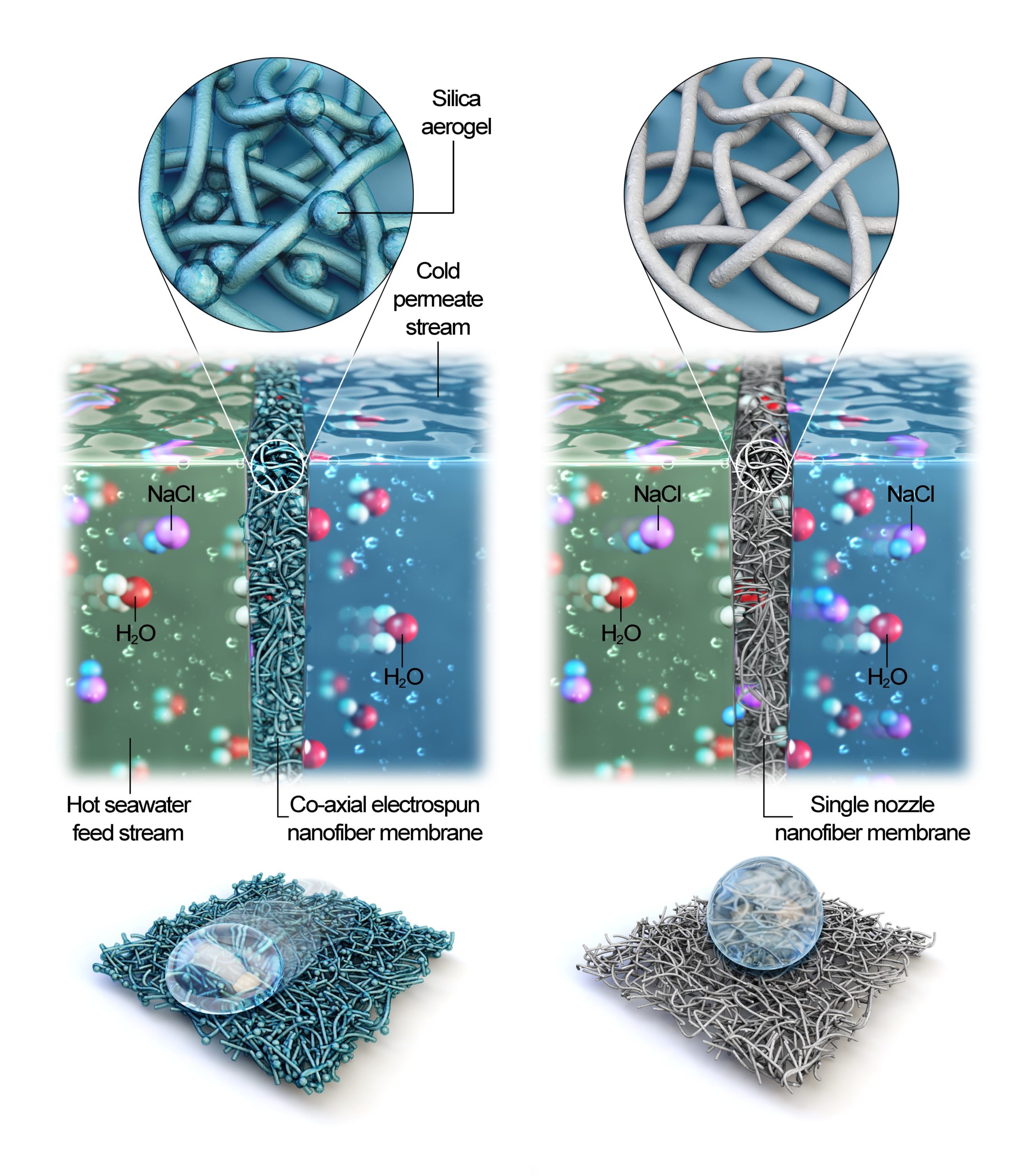

The nanofiber membrane functions as any good membrane should. It lets specific things through while preventing others from doing so. In this case, the water was welcomed to the other side with open arms, while the salt is stopped short. The membrane was made using electrospinning, which minimizes the amounts of wetting the membrane undergoes. When it comes to water filtration, wetting is a bad thing: If the pores of a membrane become flooded, the membrane ceases to act as a filter. Under an electron microscope, this membrane looks like wispy strands of cotton candy. But far from being absorbent, the membrane is hydrophobic; it hardly allows any wetting at all.

“The co-axial electrospun nanofiber membrane have strong potential for the treatment of seawater solutions without suffering from wetting issues,” said lead author Yunchul Woo, a materials scientist at the Korea Institute of Civil Engineering and Building Technology, in a National Research Council of Science and Technology press release. Woo added that the membrane “may be the appropriate membrane for pilot-scale and real-scale membrane distillation applications.”

While previous teams had used the same sort of membrane in the past, they had only operated them for about two days; the recent research rejected salt for a 30-day period.

Other means of converting saltwater into freshwater exist, namely desalination plants, but those facilities also produce tons of nasty waste products, reducing the impact of such a useful technology. Researchers also recently debuted a new technology to make water out of thin air. Whether these new methods can be scaled up remains to be seen. Nearly 900 million people lack a clean source of drinking water, and 2.2 billion need access to safely managed drinking water, according to the CDC. That alone makes improving access to water a priority. But as the world heats up and dries out — all while the population grows — it’s clear we’re going to need all the help we can get.