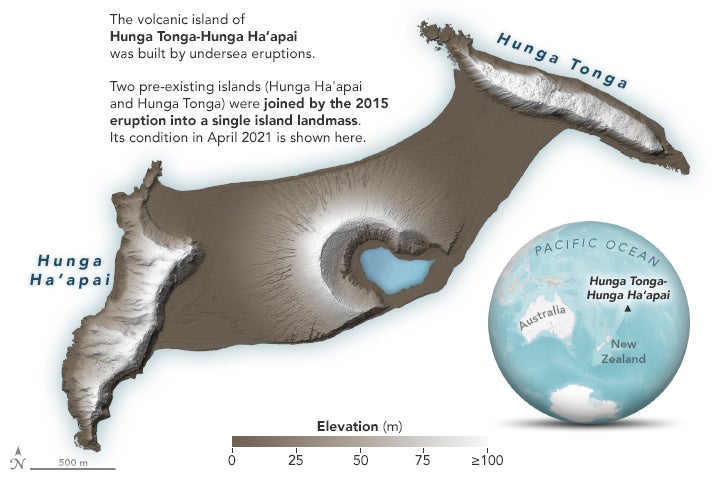

In 2015, new land emerged in the South Pacific, linking a pair of pre-existing islands, Hunga Tonga and Hunga Ha’apai. Hotel owner Gianpiero Orbassano visited the newly formed island, as ABC News reported at the time, and he, along with his son, proceeded to stroll the beaches and climb to the tallest point. Orbassano, an Italian national living in Tonga, said the island had great potential to attract tourists, despite warnings from scientists that the area could be unstable and dangerous.

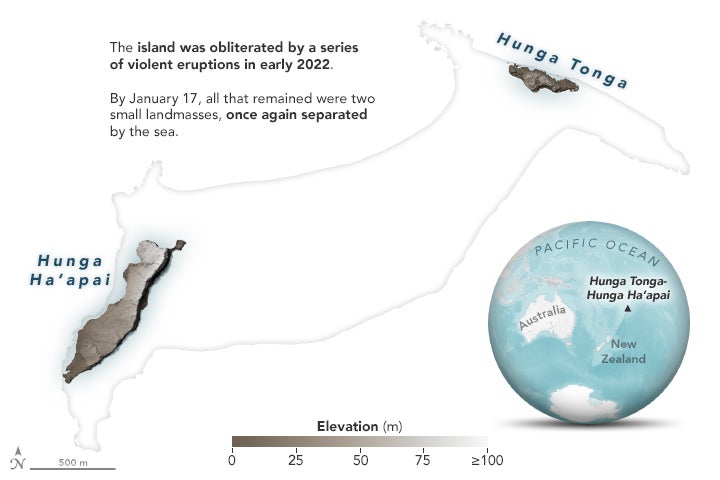

Some seven years later, it seems the scientists were right. Hunga-Tonga-Hunga-Ha’apai, as the newly formed island was named, is now a shattered version of its former self, having been obliterated in the January 15 eruption. The explosion ripped through the emerging island, triggered a destructive tsunami, covered nearby Tonga in ash, and produced an atmospheric shock wave that travelled around the world.

Scientists have never seen anything quite like it, saying the eruption may be of a previously unknown type, according to NASA’s Earth Observatory. NASA scientist Jim Garvin, along with researchers from Columbia University, the Tongan Geological Service, and the Sea Education Association, had been tracking changes to the island over time using satellites and ground-based observations.

The two uninhabited islands seemed innocuous when viewed from the surface prior to the new growth in 2015, but they represented the two tallest sections of a large underwater volcano. The volcano rises 1.8 km from the seafloor and stands 20 km wide at the base. The submerged caldera measures 5 km in diameter.

What lies beneath? Revealing the massive Hunga #caldera (5km diameter) below the water line, 3D model using elevation data @theAGU + bathymetrics @NOAA #Tonga #Blender pic.twitter.com/PmpVOfX8HD

— frédérik ruys (@fruys) January 16, 2022

The landmass connecting the two islands in 2015 had formed as a result of small but intermittent explosions and the steady accumulation of tephra (fragments of falling volcanic material) and ash. Eruptions like these, known as Surtseyan eruptions, are the result of seawater trickling in and interacting with hot materials in the vent, resulting in new landmasses and further island growth.

“If there’s just a little water trickling into the magma, it’s like water hitting a hot frying pan,” Garvin told NASA’s Earth Observatory. “You get a flash of steam and the water burns burn off quickly.”

Garvin and his colleagues were carefully watching the newly emerged landmass to study the effects of erosion, like the steady churning of waves and the impacts of tropical storms, and also to see how plants and wildlife, from shrubs and grasses through to insects and birds, were making use of the new territory. These types of islands are also rare, adding to its scientific importance; the only other notable Surtseyan island is Surtsey, which formed near Iceland in 1963 and still exists to this day.

Hunga-Tonga-Hunga-Ha’apai began to grow again in earnest when eruptions renewed in December 2021. By early January 2022, the team’s data “showed the island had expanded by about 60 per cent compared to before the December activity started,” Garvin said, adding that “this was pretty normal, expected behaviour, and very exciting to our team.”

But this dramatic growth was all for naught. Explosions renewed on January 13 and 14, sending large ash plumes into the sky. The violent explosion on January 15 sent volcanic material some 40 km into the atmosphere, while a massive stratospheric wave propagated around the world at speeds reaching 300 metres per second. On the following day, radar images showed that most of the island had been destroyed.

This wasn’t your typical Surtseyan eruption, Garvin said. “We don’t know why — because we don’t have any seismometers on Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha‘apai — but something must have weakened the hard rock in the foundation and caused a partial collapse of the caldera’s northern rim,” he said. “Think of that as the bottom of the pan dropping out, allowing huge amounts of water to rush into an underground magma chamber at very high temperature.”

High temperatures, indeed. The tremendous volume of seawater, at around 20 degrees C, interacted with magma hotter than 1,000 degrees C. All this mixing happened in a small magma chamber, resulting in the tremendously explosive eruption. “[S]ome of my colleagues in volcanology think this type of event deserves its own designation,” Garvin said. “For now, we’re unofficially calling it an ‘ultra Surtseyan’ eruption.”

Garvin estimates that the energy released by the eruption was somewhere between 5 to 30 megatons, a figure based on the amount of material displaced, the strength of the rock, and the height and speed of the eruption cloud (this is a preliminary estimate, and such a large range will have to be refined). That’s hundreds of times more powerful than the atomic bomb detonated over Hiroshima in 1945. For context, the Mount St. Helens eruption of 1980 was 24 megatons, and the Krakatoa eruption of 1883 was a mind-melting 200 megatons. Tsar bomba, the most powerful nuclear device ever detonated, erupted with 50 megatons of force in 1961.

The scientists will continue to monitor the area for signs of volcanic activity and new growth. As for the island hosting tourists, new hotels, and games of shuffleboard, not so much.