How food looks can have just as much impact on its taste as the ingredients that went into it, but all five human senses actually play a part in how we perceive and enjoy what we eat. Chocolate is a great example of this, as its snap and crackle is hard to perfect when baking but is a big part of its appeal. This has lead researchers from the University of Amsterdam to experiment with 3D printing chocolate with unique structures that emphasise the characteristics we already associate with high-quality chocolates, in the hopes of discovering ways to alter how materials fracture and enhance how people physically engage with matter of all kinds.

As our ability to manufacture and manipulate materials at the microscopic level has improved, it’s opened up a world of research around something called metamaterials. Humans long ago learned how to mix different materials to produce new ones with very specific properties; it’s the basis of the science of metallurgy, for example. But metamaterials strive to do the same by changing the structure of a given material to produce improved properties or characteristics. One of the most interesting areas of study with metamaterials is with camera lenses that look completely flat to the human eye, but are actually covered in microscopic structures that bend light as effectively as curved lenses do, further improving smartphone photography while potentially getting rid of camera bumps altogether one day.

Camera lenses and candy bars don’t seem to have much in common, but metamaterials could be just as useful to chocolate lovers as they are for photographers. There are a few factors that separate high quality chocolate from the cheap stuff used to make the giant bunnies you probably enjoyed last weekend. The good stuff has a glossy shiny finish and tends to crack when bitten into, with a distinct snap, instead of just crumbling in the mouth. That unique texture comes from tempering, a time-consuming but important process where chocolate is repeatedly melted and cooled to specific temperatures to reach a specific phase (there are six in total, and phase five is the ideal) where a desired crystalline structure forms.

Researchers from the University of Amsterdam realised that the metamaterials approach could be used to further enhance the texture and experience of biting into high-quality chocolate. This happens via creating even more snaps and fractures through a structure that is more complex than what’s created by simply pouring melted chocolate into moulds. The idea doesn’t replace the tempering process, however, which actually provided some unique challenges when the researchers turned to 3D printers to manufacture their chocolate treats.

Melted chocolate that had been tempered to reach the stage where phase V crystals form was loaded into syringes that had to be kept at 90-degrees Fahrenheit while the printer built up structures layer by layer. But maintaining that temperature proved to be a challenge, requiring constant recalibration to account for the chocolate thickening over time. Using 3D printers with a plastic extruder is already finicky enough — but trading that for tempered chocolate sounds like a real nightmare.

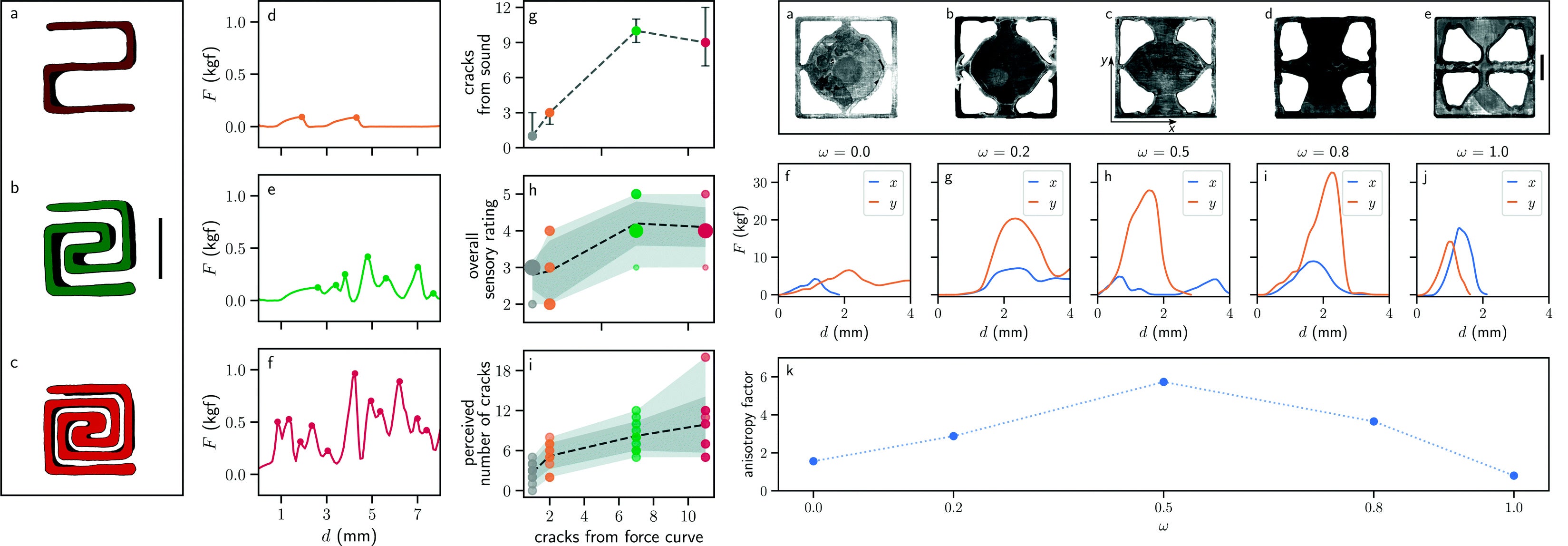

The results were shared in a recently published paper, “Edible mechanical metamaterials with designed fracture for mouthfeel control,” in the journal Soft Matter. They confirmed what the researchers speculated: the perceived quality and enjoyment of eating chocolate could be improved by increasing the number of cracks experienced while biting into a piece through S-shaped structures of increasing complexity. The researchers also found the experience could be improved by creating chocolate with anisotropic structures that alter the resistance felt during the bite through shapes and patterns that shear and break with force applied in specific directions.

Will we see companies like Lindt or Cadbury rolling out metamaterial-inspired treats anytime soon? Probably not, but the research has some other interesting applications when it comes to food. Using similar manufacturing processes, the texture of artificial meat could be improved to feel more like biting into the real thing, or altered to something completely different for those who are turned off by meat’s traditional texture. It could also be used to make foods that still taste delicious (or at least fool the brain into thinking they are) but are easier to consume for those who have issues with chewing or swallowing.