Between 2014 and 2016, the European Space Agency’s Rosetta spacecraft orbited and studied a comet hundreds of millions of miles from Earth, collecting data on the space rock’s structure and geology. Now, the ESA is asking the public to study images of the comet and to report differences in its surface features over time.

The object is Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko and was first observed in 1969. The comet has an elliptical, 6.5-year orbit. When Rosetta arrived at the object in 2014, it became the first spacecraft to rendezvous with a comet.

As Comet 67P (as it’s known for short) moved through its orbit, the Sun shone on its different sides. That gave Rosetta a hugely illuminating look at the icy rock, views that were captured in numerous images by the onboard OSIRIS camera.

“Given the complexity of the imagery, the human eye is much better at detecting small changes between images than automated algorithms are,” said Sandor Kruk, an astrophysicist at the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics near Munich, Germany, who dreamt up and began the citizen science project.

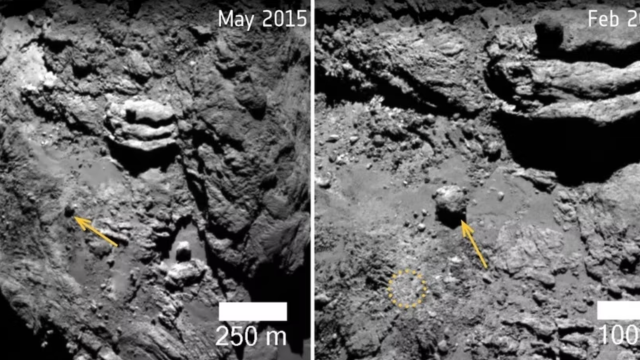

Using a tool called Rosetta Zoo, members of the public are encouraged to look at side-by-side images of features on Comet 67P that were taken before and after it made its close approach to the Sun. Volunteers can manipulate the images by rotating them and zooming in, and they can indicate the type of feature they think may be exhibited in the image (dust, boulder, or erosive features), and what’s changed about it — whether it newly appeared, disappeared, or simply moved.

“In the past few years, astrophotographers and space enthusiasts have spontaneously identified changes and signs of activity in Rosetta’s images,” said Bruno Merín, the head of the ESA’s ESAC Science Data Centre in Spain, in an agency release. “Except for a few cases, though, it has not been possible to link any of these events to surface changes, mostly due to the lack of human eyes sifting through the whole dataset. We definitely need more eyes!”

The volunteer work on the data will be used to produce maps of active areas on the comet’s surface, which scientists will be able to use to make new models of cometary activity. The more eyes there are on these pictures, the more insights can be gleaned about the ancient debris floating through our solar system.

More: Astronomers Spot Some Familiar-Looking Comets Around a Distant Star