A team of researchers scanned the roof of a limestone cave in Alabama and discovered several massive Native American mud glyphs that are estimated to be about 1,500 years old.

The glyphs depict anthropomorphic figures, animals, and abstract shapes, and were incised in the cave ceiling between the 2nd century and 10th century, according to the researchers’ calculations. They made a photorealistic 3D model of the cave and its artworks, and their study is published today in Antiquity.

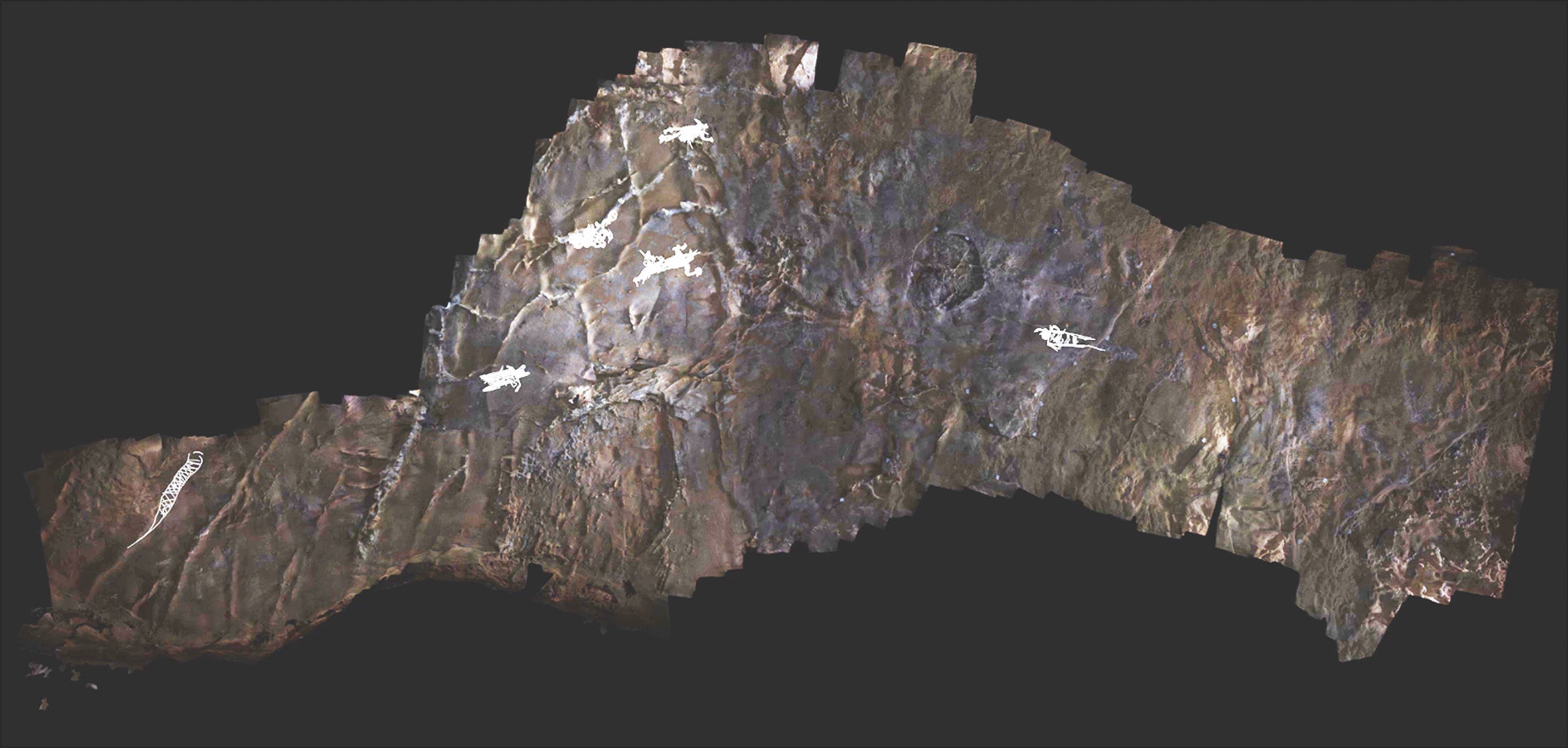

The cave is referred to as 19th Unnamed Cave, to protect its exact location in Alabama. It contains hundreds of mud glyphs that were made by Native Americans before Europeans arrived in North America. The cave’s glyph chamber is 24.99 m by 20.12 m, with a ceiling that’s often just 0.61 m high, and the glyphs are in the cave’s dark zone, meaning they are beyond the reach of natural light.

“This is not something they ad-libbed. They went in there with a plan, they knew the images they were going to draw and the scale they were going to draw them at,” said Jan Simek, an archaeologist at the University of Tennessee and the lead author of the paper, in an email to Gizmodo. “These aren’t doodles. They were planned images that clearly had meaning to them.”

Because the glyphs are in the cave’s dark zone, they would have been made by torchlight, by burning bundles of river cane. That makes Simek suspect the glyphs were made by groups of at least two people, as holding a torch while incising symbolic glyphs on the ceiling of a cramped cave would be difficult.

The cave’s particular climatic conditions mean that a thin veneer of mud sticks to its ceiling; that allowed the artists to not only make the mud glyphs but to ensure that they were preserved long term. The timeframe during which the glyphs may have been made is wide. A fragment of wood charcoal in the glyph chamber was radiocarbon dated to between 660 CE and 949 CE, while the burnt remains of a cane torch stoke found beyond the glyph chamber dated to between 133 CE and 433 CE.

The identity of the people who made the glyphs is unknown, but they are in all likelihood the ancestors of some living Americans. The exact characters or mythologies the glyphs may depict is also unknown, but they are thematically similar to glyphs and rock art from elsewhere in North America, according to the researchers.

The newly discovered glyphs are so massive that they weren’t previously noticed as discrete artworks. By scanning the entire cave ceiling, the researchers were able to stitch together images of artworks that cannot be observed in their totality in person, given the cave’s low ceiling. Not all the glyphs have been catalogued, Simek said, so the cave has yet more secrets to divulge.

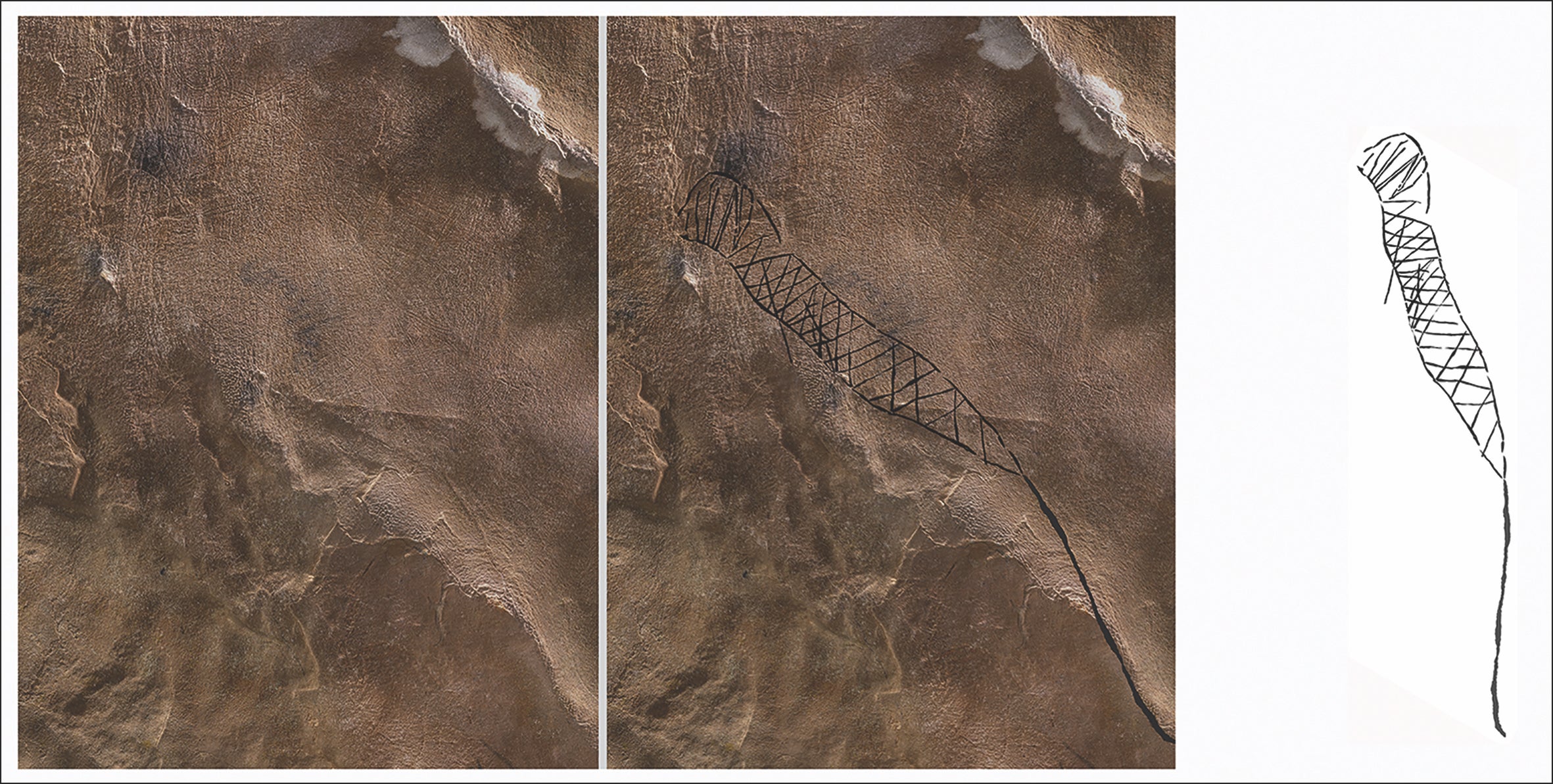

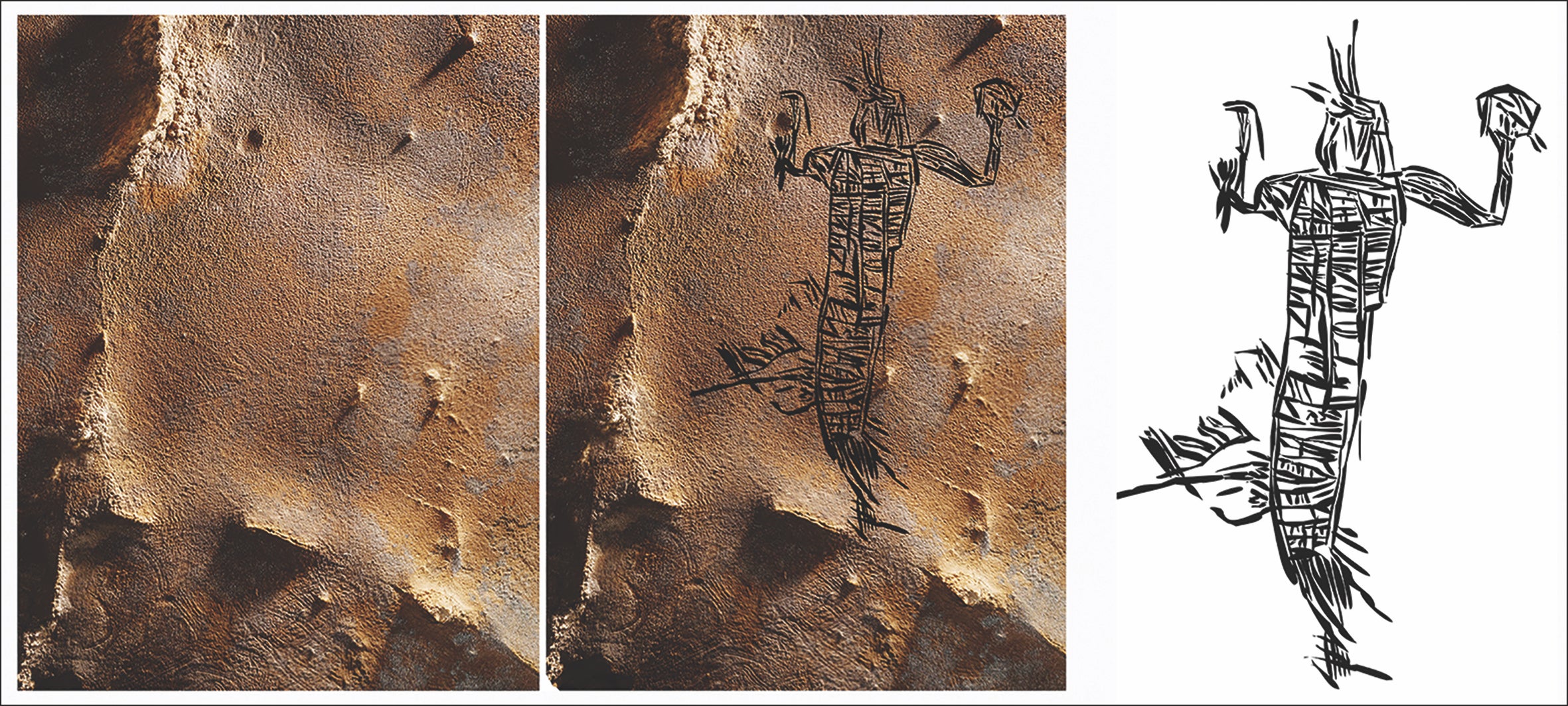

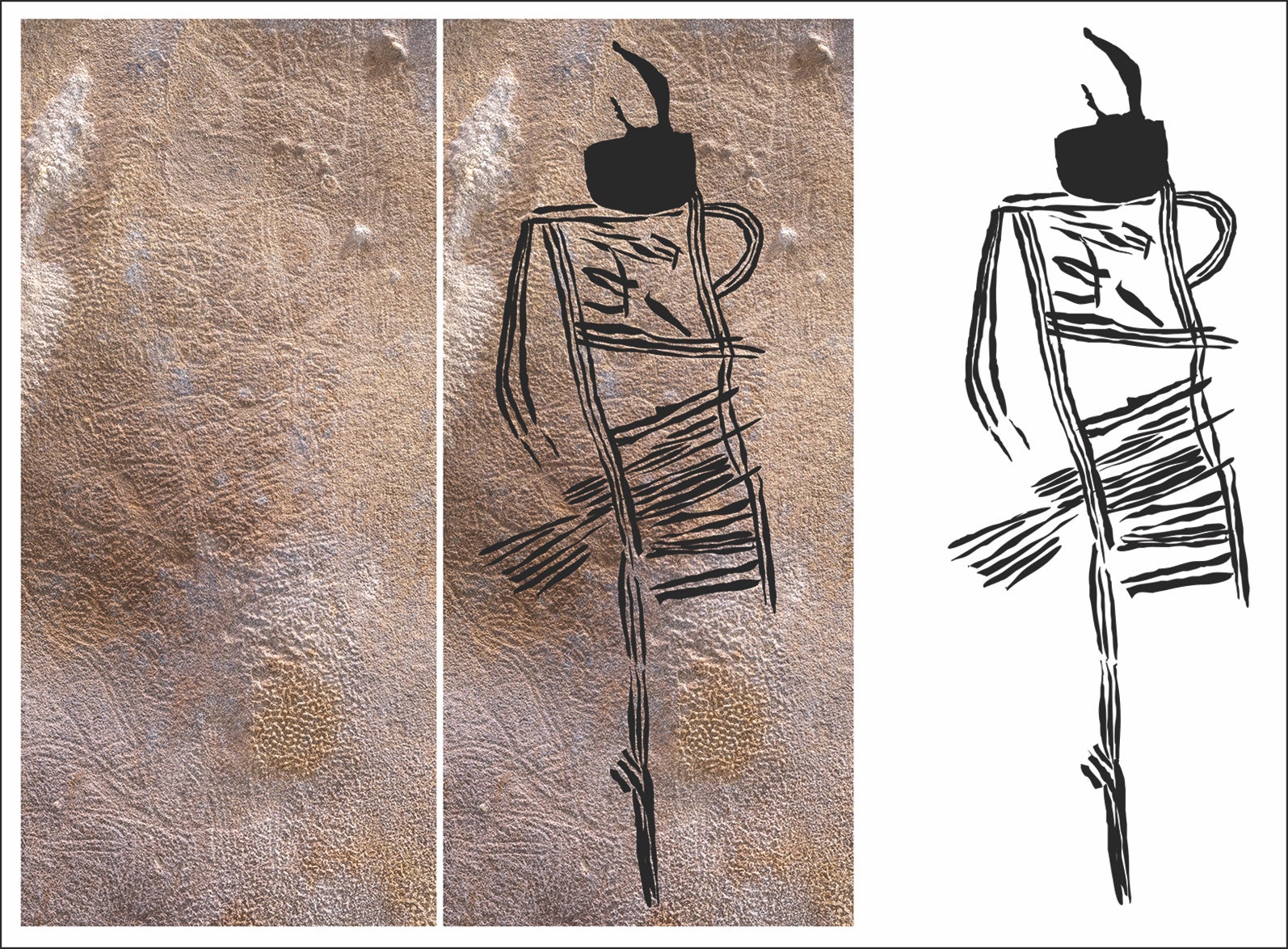

In the paper, the researchers described the five largest glyphs they found. Several are anthropomorphic, with humanoid bodies apparently wearing regalia. Two of the anthropomorphs were about 1.83 m long, and another was 0.91 m long. The largest of the glyphs is an 3.35 m serpent, with a pattern the team states is similar to that of the eastern diamondback rattlesnake (Crotalus adamenteus), which is native to the area.

The decision to carve hundreds of glyphs in a difficult-to-access, pitch-black recess of a cave may seem perplexing. But Simek said that the location would have been selected with intention. “And even if they couldn’t perceive [the art] all at once, and even if it was only certain members of the community that could perceive it, they knew it was there,” he said.

The drawings are hardly old by cave art standards: The painted scenes at Lasceaux in France are nearly 20,000 years old, and a painting of a pig in an Indonesian cave is a whopping 43,900 years old. But the glyphs in Alabama are a rare look into the culture of native people in what is now the Southeastern United States.

Large anthropomorph 1

Large anthropomorph 2

Serpent and wasp

Bird and anthropomorph

Large anthropomorph 3

Possible rattlesnake

Serpent figure