Sports cars are supposed to be light; electric cars are heavy. Changing regulations have chimed the slow death of exclusively internal-combustion engine-powered machines, and the first casualties are those marvels of engineering that prioritise performance above all else: supercars.

If you’re a company like McLaren, it’s in your best interest to keep making cars; pivoting to something else after 60 years is hard, and Bruce McLaren seemed to have few other hobbies besides driving, wrenching and water-skiing. To continue selling them, McLaren needed to introduce batteries and an electric motor. Of course, that presented a dilemma — one that the engineering team behind the new McLaren Artura was determined to solve from the beginning.

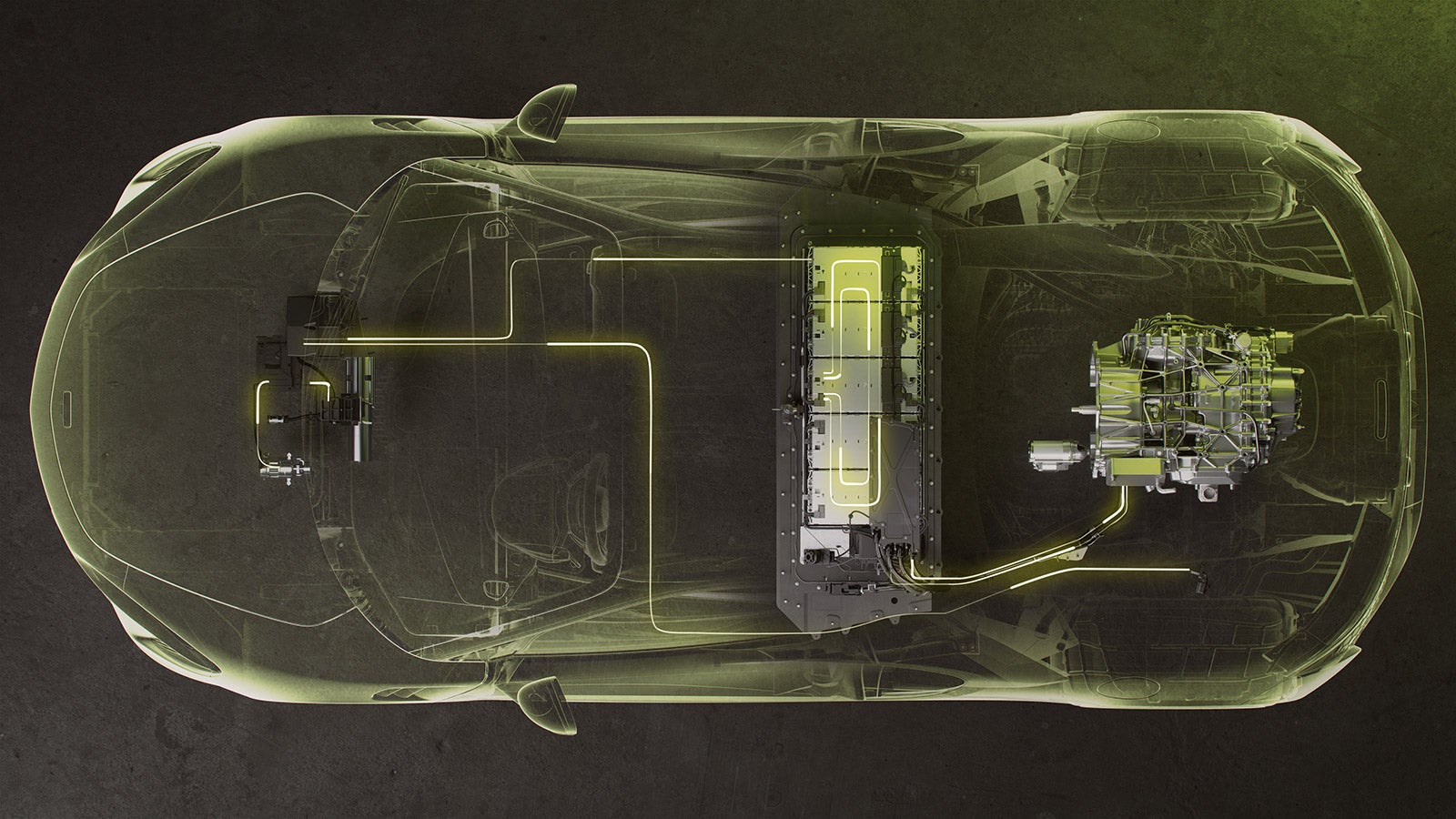

See, the 94-horsepower axial-flux electric motor and 7.4 kWh of batteries, plus all the ancillary equipment to support the Artura’s electrical system, weighs 129 kg. McLaren could’ve turned up with a 1,588 kg supercar, but that’s not really something it or many of its customers want. Instead, it went on a tear, eliminating as much mass as possible from the front to the back of its first comprehensively new car in 12 years.

The campaign touched every system — from the chassis to the powertrain, the suspension and even the seats. In isolation, none of the gains are earth-shattering. Together, they’re dramatic. The Artura weighs only about 100 more pounds than the 570S it replaces in the marque’s lineup.

It starts with the Artura’s carbon-fibre monocoque — a replacement for the Monocell introduced in the McLaren MP4-12C way back in 2010 that has formed the core of every product out of Woking since. The new design is dubbed the McLaren Carbon Lightweight Architecture, and unlike its predecessor, was made for electrification from the outset. Even while lugging the battery safety enclosure, it weighs 82 kg — just 7 kg more than the old Monocell. Two people can still lift it easily, and I know because I have, with some help.

The MCLA tub saves weight by consolidating purpose, a theme that runs constant throughout the Artura. Previously, that battery compartment would have been bolted on, as would hinged for the doors. Now they’re moulded in. The aluminium subframes that fix the to tub are also 10 per cent lighter in total than the old bones.

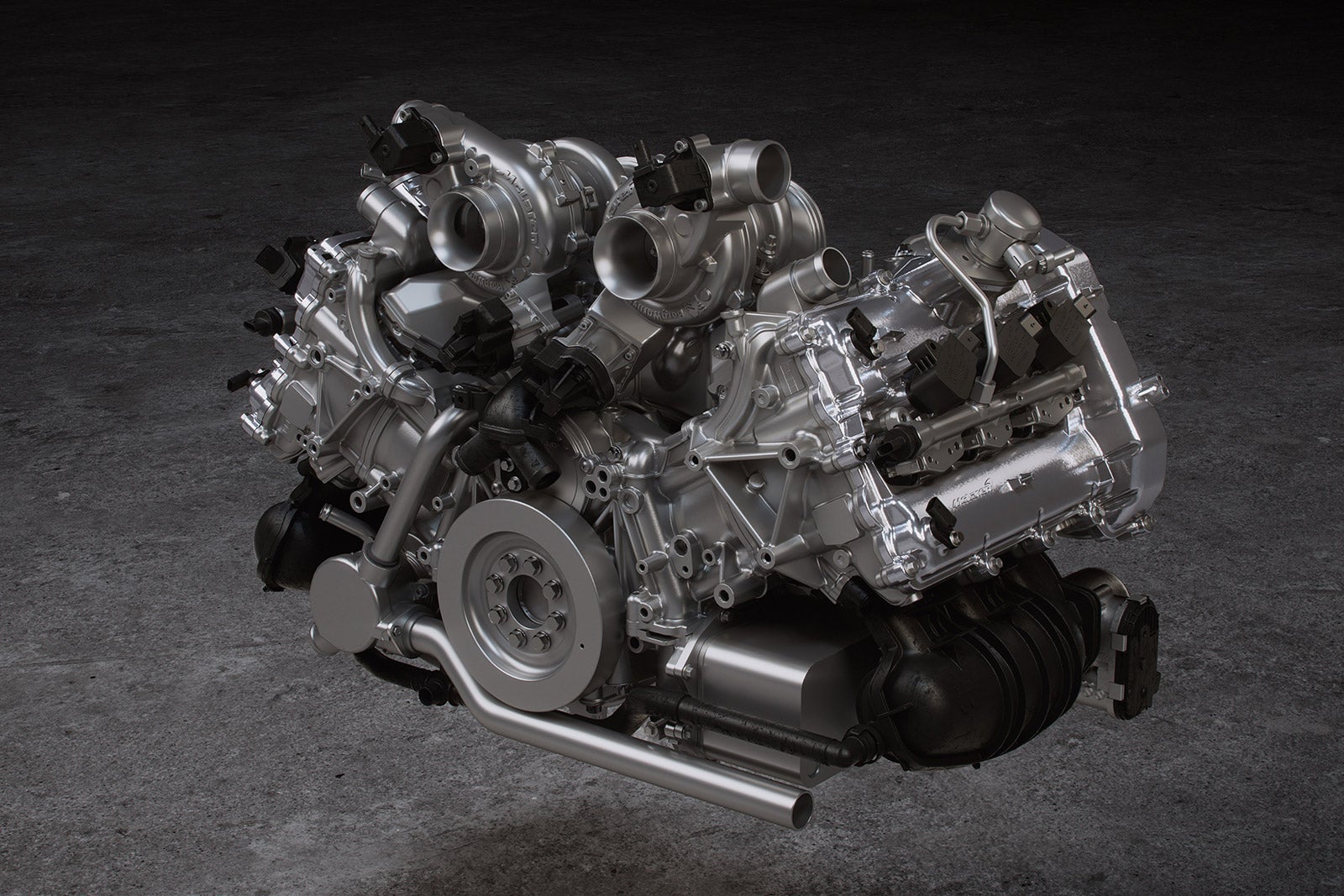

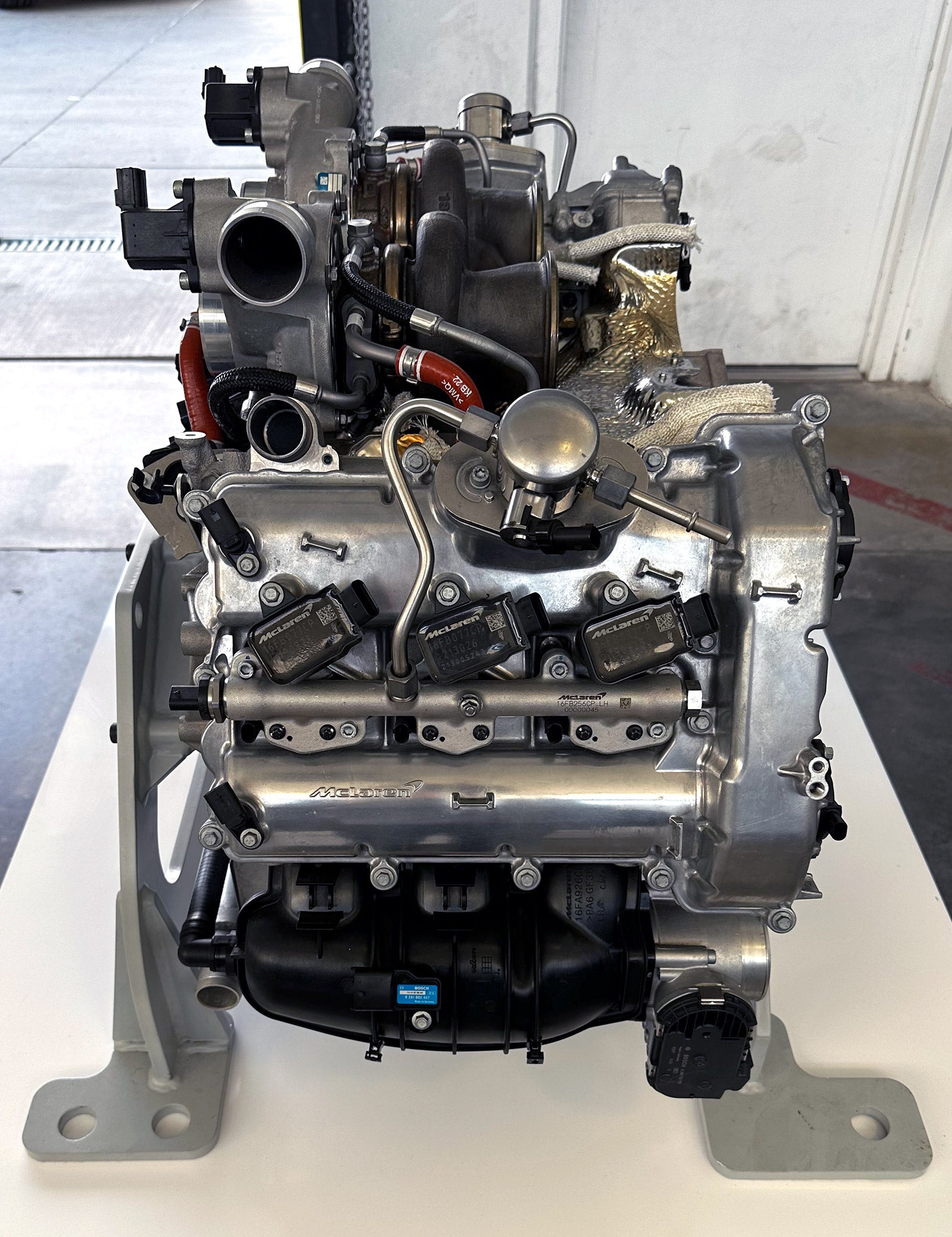

They support an engine where perhaps the most progress has been made in the pursuit of trimming fat. Losing two cylinders is the short answer for how the new three-litre, twin-turbocharged M630 120-degree V6 sheds 50 kg compared to McLaren’s previous M8-series V8. The company leaned on that old motor a lot — it was present in every single one of its modern production cars, if you don’t count the naturally-aspirated Judd V10 inside the new Solus GT.

But lopping off cylinders alone wouldn’t get the engine to be quite as compact as it is. Because alongside weight, length — namely, reflected in the wheelbase — is something the company was extremely keen to keep in check.

Take the distance between the cylinder bores, for example. Every couple hundred microns saved is basically doubled, on either side of the bore. But physically optimising it to that degree takes phenomenal precision — which is where 3D printing saves the day. Not for the engine block directly, but for the core of sand that the block is cast around, as chief engineer Geoff Grose explained to me.

“The spacing between the cylinders — we kind of think, how close can we get the cylinders together,” Grose said. “It’s basically like the minimum thickness for the wall thickness of the metal, and then we still need a water jacket all the way around. So this is why we have this 3D-printed sand for the cores for the casting. So the casting of the engine block, you end up with this really narrow little sliver of a sand core. But by printing it, you can get much better dimensional accuracy to be able to make it that narrow.

“And then you bring the cylinders closer together. It makes the whole thing shorter. If you make the crankshaft shorter, then its inherently going to be stronger, stiffer — you haven’t got to grow it in other dimensions. So one thing leads to another, I suppose.”

It’s a good example of how one gain rolls into positive benefits for other aspects of the engine or, broadly speaking, the entire car.

“Everything along that drivetrain is going to add to the wheelbase,” Grose said, as he pointed to a wireframe diagram of the Artura. “Every millimetre is going to add to the wheelbase, because we’re positioning the front of the engine here, and then we’ve got the battery and the fuel tank, so we’ve got to really be in control of that. And then, anything you’re stacking [between those components and the engine] is just going to push the axle further back. So [we] really fight for those millimetres.”

Another change to the M630’s layout made for packaging reasons actually had the secondary effect of moving potential for noise, vibration and harshness away from the passenger cell.

“This also kind of shows one of the reasons why we moved the valvetrain to the back of the engine — all the chain drive for the cams and things which, traditionally, is at the front of an engine,” Grose explained. “You always call it a front end auxiliary drive — that’s standard terminology for it. But when it fits at the front on a mid-engine, it means that you’re growing the package [just behind the cabin] where you’re kind of bringing the body in at an angle, so actually you want to keep the nose of the engine low if you can — it’s easier to manage the height further rearwards. So we just swapped it round.”

All these optimizations and more combined for an engine that’s not just lighter than the M838 or M840, but tighter in every dimension. Even with the wide 120-degree bank angle, the M630 is 8.7 inches narrower than the M840. The top of the engine also measures two inches below where the V8 peaked, which was the big factor in choosing 120 degrees to begin with: lowering that centre of gravity, while leaving just enough space to nestle those intake manifolds below and turbochargers between.

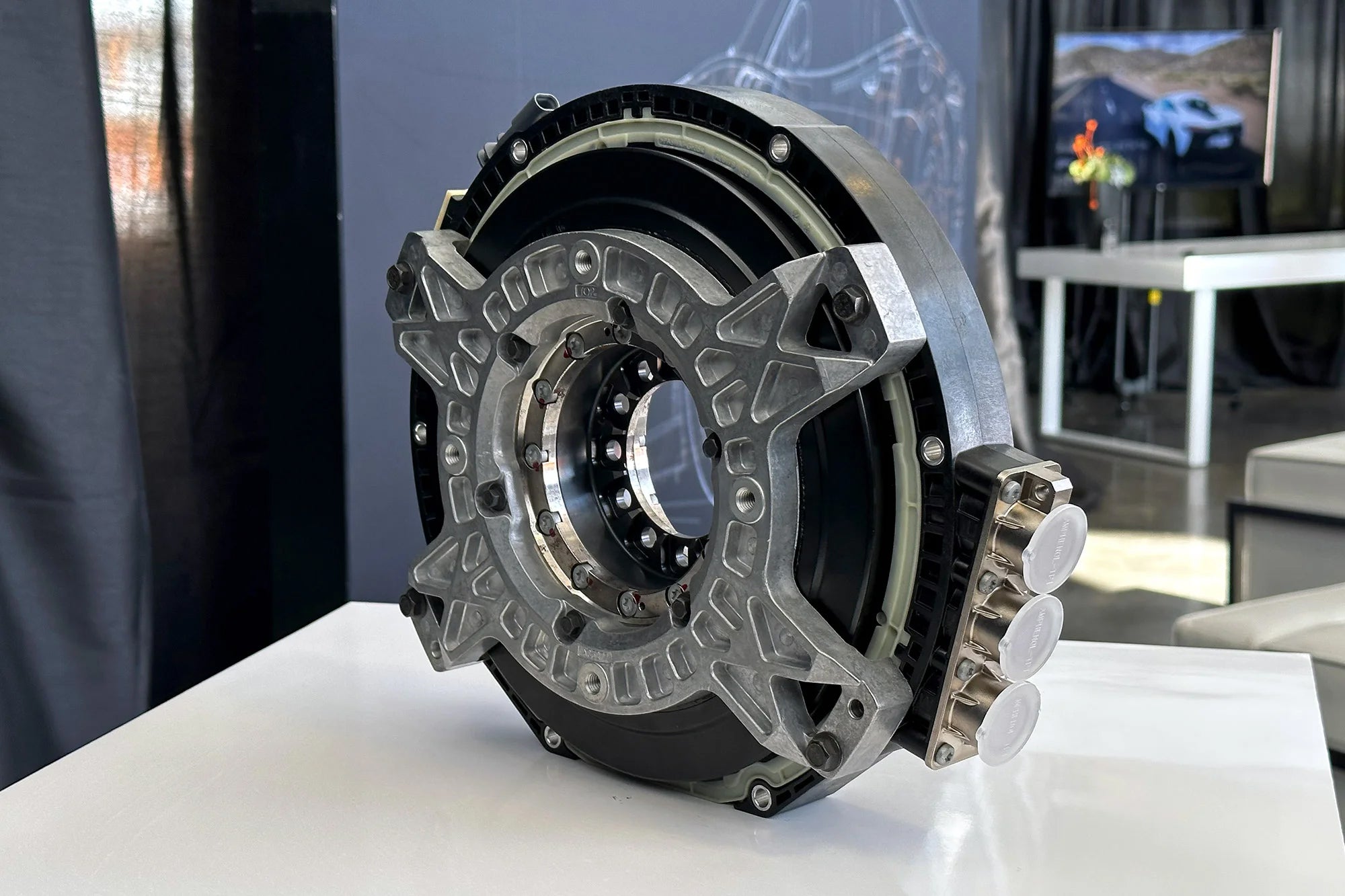

The new eight-speed transmission offered an opportunity to claw some millimetres back, too. The axial-flux motor sits within the bell housing of the gearbox. In addition to the instant torque it offers the powertrain and almost 32 km of all-electric cruising, it’s also designed to replace the reverse gear. Then there’s the new Ethernet electrical system, which cuts wiring length by 25 per cent and weight by another 10; and the consolidated exterior panels, which saves on manufacturing complexity. The entire rear clamshell is one piece — you have to hunt for shut-lines on this car.

The styling team is thankful for each of these little wins, Grose told me.

“Designers like to have some overhangs to play with, to make the proportions look nice. They really want the wheels to be right out at the corners. And then also, we kind of stack it up because we want the driver sort of central, as low as possible — but then we want the battery right low as well.”

Without the total space saved, the Artura would be a longer car; the profile might not work the way it has so well. From the outside it’s not particularly distinctive from previous McLarens, but maybe that’s the point: the ideal that even despite the cons of electrification, with a little ingenuity supercars can look as striking as they always have, and drive just as well or better. “We manage weight like we manage cost,” Gross handily summed up. You don’t get results any other way.