120 years ago, Orville and Wilbur Wright piloted their gasoline-powered biplane for a record-breaking 12-second flight, the first successful, powered flight with a pilot aboard. Later this year, NASA will attempt a fresh feat in the world of aviation: the agency’s first crewed flight of an entirely electric plane.

The plane is the X-57 Maxwell, a product of NASA’s quirky suite of experimental X-planes. Should all go according to plan, the craft will be in the air for around 20 minutes for its first flight, according to its pilot, Tim Williams. The X-57 team is a winner of the 2023 Gizmodo Science Fair for their eight years of work toward getting the plane off the ground.

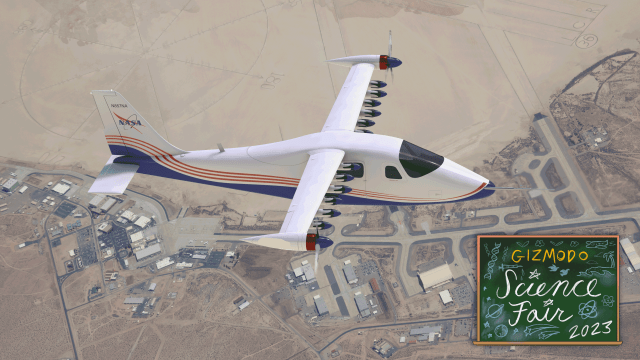

Like most modern aircraft, the X-57 looks nothing like the Wright Flyer; however, it still looks distinctive compared to its contemporaries. The aircraft is a repurposed Tecnam P2006T, with the plane’s typical twin engines swapped out for a set of 14 propellers, which draw power from two lithium-ion battery packs tucked into the cabin behind the pilot’s seat.

The battery and propeller system is the product of nearly a decade of research at NASA flight research centres across the country and collaborations with private companies. Should the aircraft take off this year, it’ll be NASA’s first crewed X-plane flight in 20 years.

Originally, the electric plane wasn’t even the plan. The team was researching a new type of wing back in 2014.

“We wrote down, ‘this project’s going to research a high-lift wing,’” said Sean Clarke, principal investigator on the X-57 project. “That’s the point of the project, is to put electric motors in a novel way onto the wing so that the wing can be very efficient at cruise but still generate lots of lift for takeoff and landing, and have a higher performing aeroplane as a result of incorporating the electric technologies.”

In 2015, the wing and propellers were hoisted on top of a modified big rig, which raced down the dry lakebed at Edwards Air Force Base in California like an agency cosplay of Mad Max. This was the Hybrid-Electric Integrated Systems Testbed (HEIST), a project that paved the way for the X-57 Maxwell.

The big rig was driven to test a system of 18 electric motors and propellers fastened to a large wing. The tests determined the propeller system generated plenty of lift, clearing one of the main hurdles of the project.

“A couple of years later, we changed the formal goal and objective of the project, because we realised that’s not really the point. No one’s going to go buy that particular wing from NASA and build a fleet of aeroplanes around it,” Clarke said. “The point of the project is for us to go through the process of designing the wing and learn lots of lessons and tell industry about it.”

Electrically powered flight has a long history. In 1884, two French military engineers launched La France, a hydrogen dirigible powered by an 8-horsepower electric motor. La France made the first round-trip flight by an aerial vehicle, relying on a zinc-chlorine battery for its power.

In 1918, a Hungarian-Czech team managed to fly a tethered rotorcraft carrying four people, though its motor gave out during its fourth flight.

Demonstrators in the 1970s and 1980s also showcased how aircraft could fly using battery power and solar power, though none of these aircraft saw their technologies scaled or put on the market in commercial ventures.

Electric propulsion flights are much more environmentally friendly than flights that use jet fuel, but they cannot travel nearly the same distances. Batteries that carry enough power for such flights, that are also compact enough, simply don’t exist yet.

In building the X-57 Maxwell, NASA engineers have been able to develop new technologies, including a scaled-up lithium-ion battery. More work is needed to develop batteries that can handle longer flights and power larger aircraft.

It’s possible that this big dream remains technologically impractical or economically impossible. But the battery and propeller technologies being deployed in the X-57 could define what fully electric flight can look like at scale for smaller aircraft like private jets.

The first electric seaplane, called the eBeaver, flew in 2019. In September, the electric commuter plane Alice took its first flight, an eight-minute jaunt out of Moses Lake, Washington. Both aircraft use electric motors built by MagniX, a manufacturer based in Washington; neither aircraft has been certified by the Federal Aviation Administration to carry passengers. MagniX also uses liquid cooling systems on its electric aircraft, while the X-57 team has solved for that: The propellers are air-cold, meaning that they don’t need an additional system to cool them down.

The X-57 is being developed in a sequence of four different modifications, or mods. You can read a bit why they develop each mod separately here. Each mod iterates on the previous one, developing and integrating new technologies, making the aircraft look less and less like a Tecnam P2006T and more and more like the final, 14-propeller aircraft NASA wants to get off the ground.

Slight changes, like moving the cruise motors from close to the fuselage to the tips of the wings, allow the plane to recover energy that otherwise would be lost, making it more energy efficient. When the name of the game is making sure the batteries are small enough to fit in the plane but robust enough to keep it in the air, energy efficiency is critical.

Mod II of the X-57 will be the aircraft that flies in this year’s first test flight, which is slated for later this year. We’ll be watching.

Read more: NASA’s X-57 Maxwell Could Bring Aviation Into the Electric Future