The trial of the century came to a thrilling end yesterday. I’m talking, of course, about the Gwyneth Paltrow ski accident trial. Terry Sanderson, a doctor, sued Paltrow for $US300,000 ($416,460) in damages after he says she ran into him at a Utah ski slope in 2016; the actor and lifestyle influencer countersued for $US1 ($1) in a widely televised trial, claiming that Sanderson ran into her that day.

On Thursday, a Utah jury ruled in favour of Paltrow, deciding after just two hours of deliberation that Sanderson was at fault for the accident. But could other, more nefarious factors have been at play — say, climate change?

Skiing looks different than it did a few decades ago. Across the world this winter, famous slopes struggled to stay open amid balmy temperatures and little-to-no snowfall. Paltrow’s accident happened at the Deer Valley Resort in Park City, Utah; a 2021 review of Utah ski resort temperature data since the 1980s shows that the state’s ski resorts are seeing increasingly warmer minimum temperatures, which is affecting the available snow.

I decided to use my substantial journalistic skills to conduct a hard-hitting investigation into the question: should climate change have been on trial along with Paltrow and Sanderson? Could toasty temperatures or mushy snow have made a collision between the retired optometrist and the Goop guru more likely or worse?

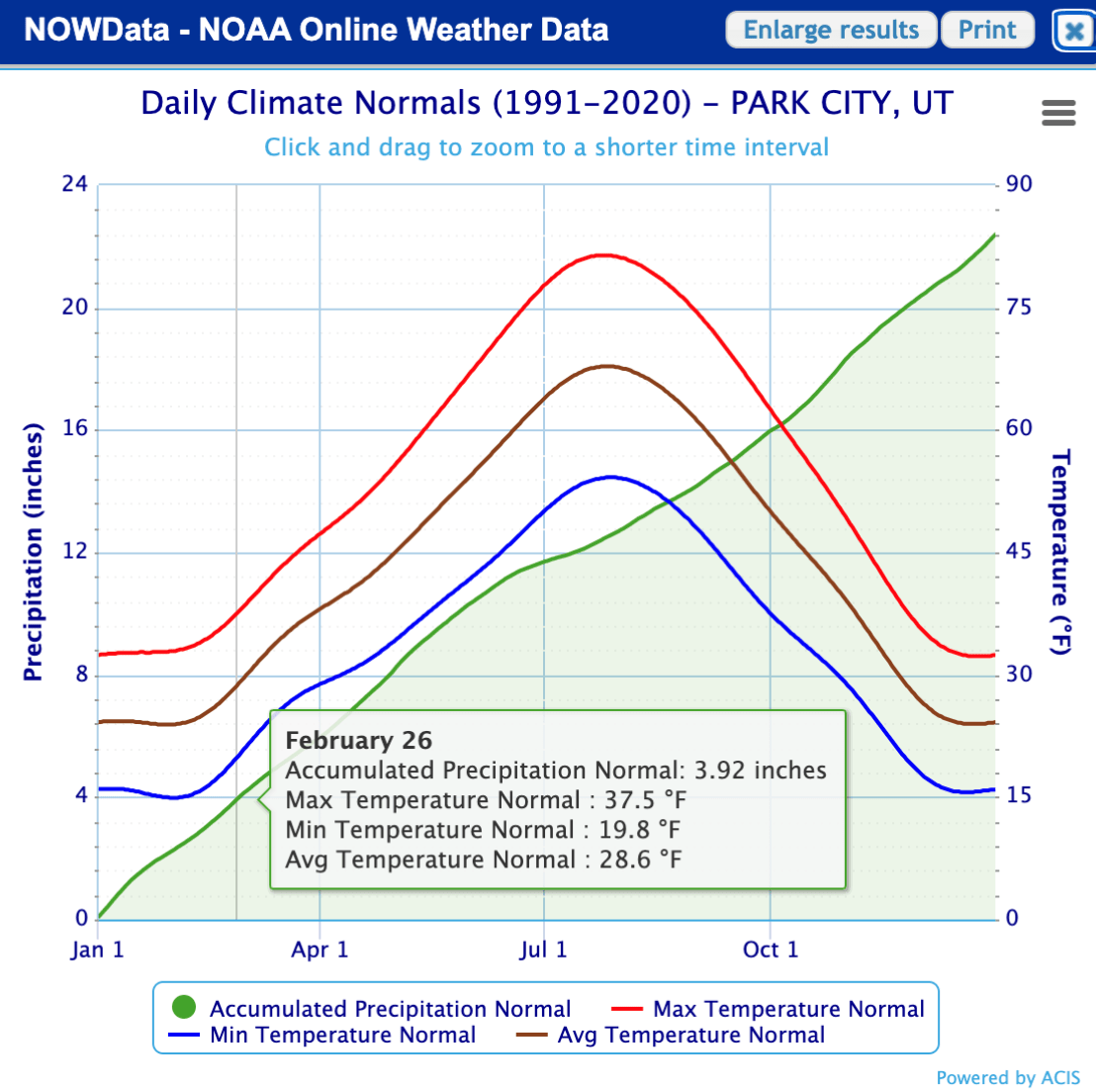

First, I thought, could we perhaps blame the crash on an unusually toasty February day? According to historic temperature records for February 26 from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the day of Paltrow and Sanderson’s accident, the high for Park City was 47 degrees Fahrenheit — substantially above the normal max temperature for that day of 2.8 degrees Celsius. The day’s average temperature was 1.9 degrees Celsius, comfortably above freezing.

Temperatures above freezing during the day and shooting back down at night can contribute to a variety of conditions that make skiing harder. Maybe slushy snow was to blame for Gwynnie careening into Sanderson (allegedly) or for the more experienced Sanderson bumping into her, as she claims in her countersuit.

While the day certainly was balmy, it turns out that snow conditions on any given day are a lot more complicated than just checking the temperature forecast. “There’s a whole science to snow,” said Daniel Scott, a professor at the University of Waterloo in Ontario and an expert in the impacts of climate change on the ski industry. While melted snow during the day during warmer temperatures can freeze back overnight, Scott explained that resorts can add grooming to avoid icy surfaces and keep snow fresh, even if temperatures are high. Snow grooming, Scott added, is “as much of an art as it is a science.”

Plus, there’s altitude to consider. According to the resort’s trail map, the run where Paltrow and Sanderson crashed, a green beginner slope called Bandana, sits at the top of Flagstaff Mountain — at 2,743.20 m above sea level, some 609.60 m above Park City’s elevation. Temperatures at higher elevations are colder than at lower levels; the mountaineering rule of thumb dictates that you subtract 3.5 degrees Fahrenheit for every 1,000 additional feet of elevation, which would put the average temperature on the Bandana slope that day below freezing. Even if temperatures were at their peak for the day when the accident occurred (around lunchtime, according to the lawsuit, so not out of the question), that’s still sitting at around 4.4 degrees Celsius — much closer to freezing than at base camp.

OK, so higher temperatures that day may not have been to blame — but what about the snow on the slopes that was available? Reports from the 2015-2016 ski season show a substantial dip in snowfall for the month of February, as snowfall fell “below normal.” NOAA data shows several days of no precipitation and no new snow before the accident. Perhaps Deer Valley had to rely on making artificial snow, which could have affected the severity of the crash; Sanderson’s claims about his injuries, after all, are extremely serious. A report issued last year before the Beijing Olympics, which made history for being the first winter Olympics to use almost entirely artificial snow, warned that increasing use of artificial snow could make skiing more dangerous and falls more painful.

While he can’t speak to the conditions of the slope on Paltrow and Sanderson’s unlucky day, Scott “doesn’t buy” the claims about fake snow being more dangerous.

“Machine-made snow can be as fluffy or as dense as you want it to be — it’s just how much water you put in it,” he said. “And once the groomer’s gone over stuff, it’s pretty dense.”

I reached out to Deer Valley to ask about the resort’s snowmaking schedule; a representative let me know that the resort usually is finished with snowmaking for the season by the first week of February. “We believe it is unlikely to have played a part in the on-mountain incident between the two guests currently at trial,” the representative wrote.

So February 27, 2016 may not have been a particularly treacherous day on the slopes due to toasty temperatures or icy artificial snow. But, as we love hammering home all the time on this website, individual conditions on any given day do not disprove the larger trends at play. Just because the snow may have been crisp and perfect for Gwynnie to ski in that morning and the temperatures not terribly above freezing does not mean that resorts like Deer Valley aren’t undergoing long-term, sport-altering changes as the planet warms. The same study that found Utah’s ski resorts are undergoing rapid warming also projects that, if the world continues on the same emissions trajectory it’s on now, the state’s ski resorts could warm by almost 6.6 degrees Celsius by the end of the century.

“We’ve probably seen peak ski season ever in the U.S. market,” Scott said. “Even with tremendous snowmaking capacity, warming is [so strong] that it’s overcoming that capacity.” While some places, like California, have seen a fresh influx of snow and a great season this year amid successive destructive storms, that’s not enough to make up for the impacts of years of repeated drought.

“There’s only so many bad years you can have,” Scott said.

While the trial covered the supposed physical, emotional, and mental ramifications of a day on the slopes, it didn’t include the climate impacts of ski tourism, especially when factoring in travel. Paltrow has been known to take both private and non-private flights; even just one private jet trip from her home in Santa Barbara to Salt Lake City would create almost as much CO2 emissions as the average European citizen does in a year. Given that this trial took place in Utah, a state where Paltrow does not live, there’s no doubt there was a lot of flying back and forth just to fight over who bumped into whom on a ski slope that’s changing each year under warming temperatures.

The travel impacts of ski tourism are so high, Scott said, that any conversation about the impacts of snowmaking — which can use a lot of water and energy — needs to include a balance of just how many people that snowmaking might prevent from hopping on a plane in search of better skiing.

“If you keep people in their state or province, if you convince them to not get on an aircraft to go skiing, you’re part of the climate solution because you’re keeping them local,” he said.