When Marvel Comics cancelled The Unbeatable Squirrel Girl in 2019, it might not have seemed like a surprise. After all, for a publisher that puts out 60-plus comics each month, cancelling one book doesn’t seem like anything to write home about — especially when that book was centered on one of the most oddball, unusual, and formerly obscure characters in the entire Marvel Universe. But Squirrel Girl’s artist-writer team of Erica Henderson and Ryan North had done something almost unheard of at a major comic company: ended a solid-selling series on their own terms.

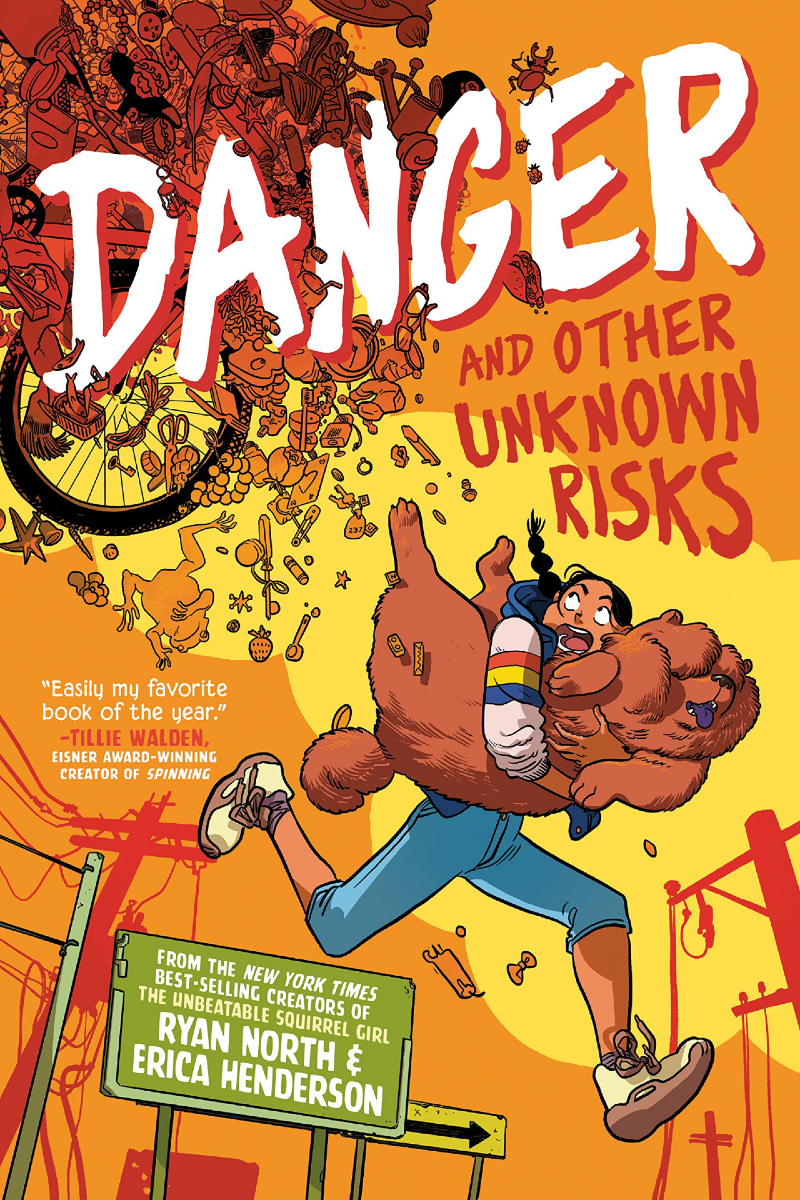

Four years later, Henderson and North have teamed up again for the original graphic novel Danger and Other Unknown Risks, released by Penguin this week. The book tells the story of Marguerite de Pruitt, a teenage girl raised up her whole life to be ready for worldwide disaster. On December 31, 1999, that disaster comes not in the form of the Y2K bug, but from a world suddenly overtaken by a flood of magic. With that premise, North and Henderson have spun a story of Marguerite, her talking-dog pal Daisy, and their adventures in a new world. The creators sat down with Gizmodo to talk about what surprises they have in store.

Erica Henderson: No! I actually usually don’t like fantasy, because I feel like fantasy for a long time has been constrained by the ideas of what fantasy is, or what fantasy should be. So I’m often kind of bored with it: it’s just, like, “OK, I read Tolkien in middle school. It’s fun. I don’t need to read a version of it again.” So I think I was often dismissive of a fantasy, but I don’t think that means that it’s not a genre worth delving into.

Ryan North: I didn’t read a lot of fantasy. I remember being in middle school or high school and thinking, why would anyone read fantasy? Because you could be reading science fiction instead, which is the exact same thing, except it’s going to happen one day. Why would I have an orc when I could have a Klingon? But I think, and this is sort of where the larger culture has gone to, that they’re kind of both sides of the same coin. You’re doing speculative fiction. They’re not that different. So for me, it didn’t feel like stepping into a new genre as much as it felt like doing something with Erica that was not unlike some of the stuff we explored before together with the superhero stuff.

Henderson: The questions we were asking ourselves were more, “What is it in general in fiction that’s been bothering us right now?” And we were sort of upset about the fantasy tropes of more recent stuff where they’re trying to create these lineages that are important for some reason. And we were questioning that narrative a lot: the Chosen One, the special family. And you see this a lot in franchises: “Here’s the Ghostbusters! And their kids!”

io9: At what point did you home in on that Chosen One trope as the cliché that you wanted to tackle?

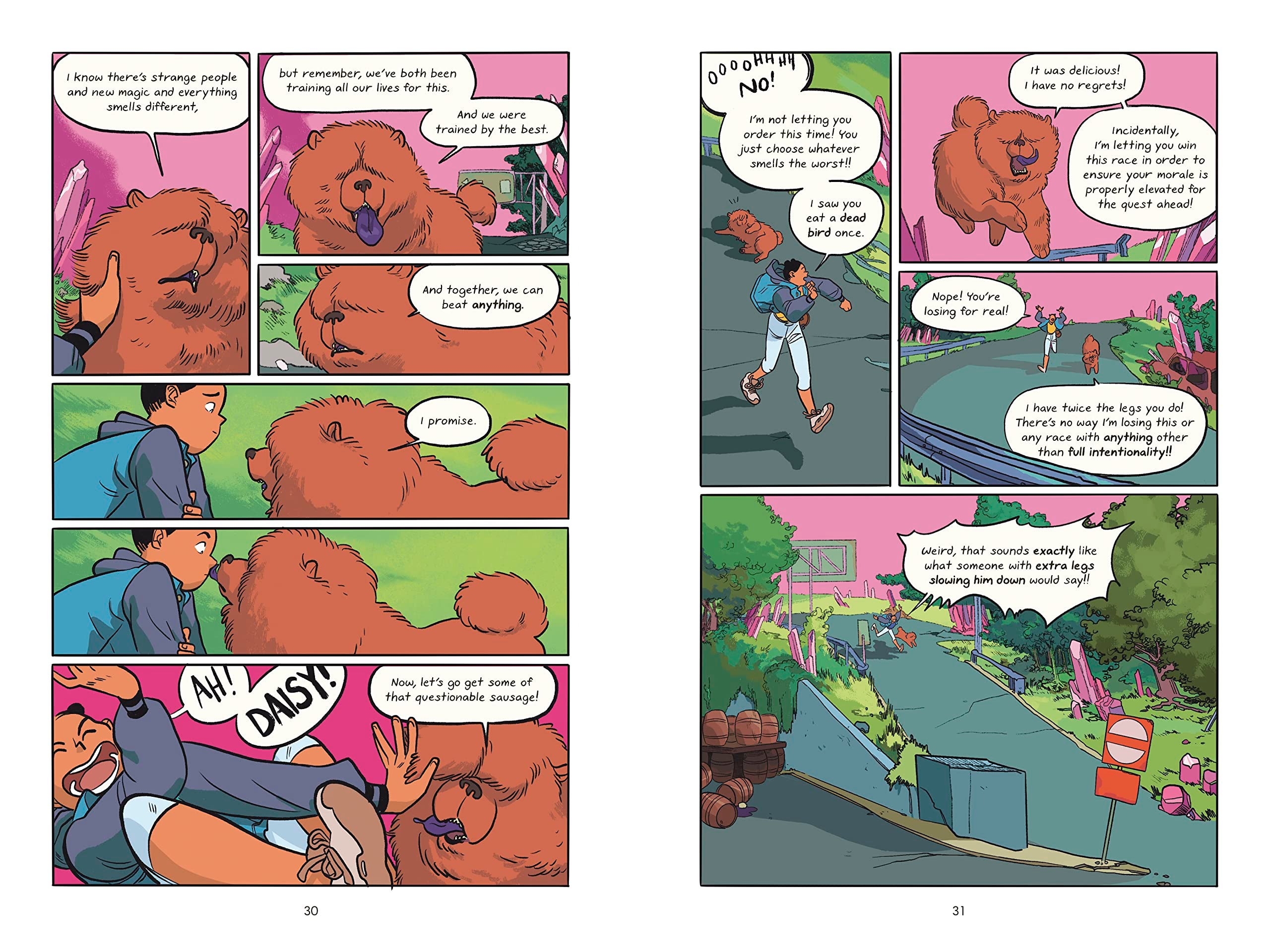

North: Very early, I think. I remember, I was like, “Explain your country to me: a country that was founded explicitly on rejecting the divine right of kings to rule, and then you tell yourself these stories about people who have this inborn right to be special.” And she’s like, “I can’t explain America to you, but let’s talk about that.” We threw around tons of different stuff, and Erica reminded me last week that I kept saying “there should be a talking dog” to every idea she pitched. And finally she was like, “OK, well, let’s do something that supports a talking dog if that’s what’s important to you.” The first thing that was definitely nailed down was talking dog, and it just built outward from that.

io9: The art in this book has, in some ways, a more realistic and almost gritty edge, even though it retains a very strong animation flavour. Was that a natural evolution for your style, Erica, or a deliberate decision to give this book a different kind of look?

Henderson: I think it was a combination of a natural progression, and I do think it gets darker than Squirrel Girl does. I feel like with Squirrel Girl, there was always an idea to keep it more positive.

North: I’ve said before that my guide to writing all-ages is “everybody keeps their clothes on, and nobody swears.” You trust readers to go there with you. But you’re right, [this book] touches on stuff you don’t normally see. The funny thing with that is that because Erica brought me in after she had this book contract, I didn’t super know what we were aiming for: I was just writing what I thought was cool. And it wasn’t until a couple of drafts into it that I realised this was being published under a YA imprint. So I think that helped, because I was never aiming for that initially. I wasn’t aware of those walls when it was being created.

So there are parts that expand outside the genre from what you normally see. The advantage of a genre is that it tells you what a story is going to be, and it gives you the broad brush strokes, but you don’t want it to be a straightjacket that restricts the kind of things you can do. And I think not 100% knowing this was going to be in the teen space while I was writing it gave it some more complicated ideas you don’t normally see explored in this space.

Henderson: I think for me, I was thinking about this stuff not so much, like, “who’s going to read it,” as “this is a person who’s going to be going through certain things” And that’s sort of where I feel like in YA, there’s been this push of, like, “Well, if it’s for young adults, there’s going to be more violence and romance, and there’s always going to be some sort of love triangle.” And that was less interesting to me than something like, “hey, what’s it like to leave the house for the first time, and have to deal with everyone else in the world?” Or, you know: “what kids are really upset about right now is that the world is boiling.”

io9: That’s another interesting thing, because this is a book about a post-apocalyptic society, but it seems in a lot of ways to have a more optimistic view of the post-apocalypse than most fiction. How did the two of you decide that was the philosophy you wanted to adopt?

Henderson: Part of it is that we looked at things that are post-apocalyptic in fiction, and more often than not, it’s about how everything’s over, and we’re doomed, and there’s nothing you can do about it except eat each other. But these sorts of things have happened to people before. Like, civilizations have collapsed. Volcanos have gone off. Floods have happened. And there are people who will do bad things, but also people tend to help each other and rebuild, even if things don’t wind up being perfect — because there’s no such thing as perfect. We always keep moving along. It’s sort of how people work: we’ve been doing it since we first figured out that you could help each other get meat and berries.

North: A friend of mine who likes horror movies sees these post-apocalyptic zombie [films]. And she said to me once, “Who wants to live that badly that they’re going to start killing their friends? I’m fine to die. I’m not going to be that person.” You’ve never seen the person in the story who’s not, like, hell-bent on ensuring that they survive at any cost. And that’s interesting: there are different people and different responses to a large change. It’s treated as an inevitability, and I’m not certain it needs to be.

io9: A lot of the trademark elements of Squirrel Girl are scaled back here. One is that there’s much less dialogue, and much more relaxed pacing. Was that a conscious choice that you made, or did you just find the art telling the story more than the words?

North: With Squirrel Girl, it was a monthly comic, and they’re not cheap, so part of the idea of the density was to make it feel worthwhile: let’s make it take more than a couple of minutes to read; let’s literally cram jokes in the margin, and make it as dense as we can. But with a graphic novel, you have space to stretch out. And also — not that anyone does this mental calculation — but the price per panel is a lot less in a book than it is in a monthly comic book. So it felt like we had room to let it breathe.

Henderson: Also, as I got further into knowing about lettering, and how much could go on in a word balloon or in a panel, there were little ticky-tacky things that I would take out as well. I think it was Jamie McKelvie who said to me, “Twenty-five words in a balloon. That’s the limit.” Otherwise, it gets you to gloss over it. So there would be times when I was like, “All right, take out two words here. It still reads fine.”

io9: The book gets heavily into the question of whether the past was ever superior to the present, and what that means for rebuilding society. Do the two of you feel like our own society is being overtaken by nostalgia?

North: It’s happening today or yesterday with the U.S. government questions about TikTok, where you see these leaders, people in positions of power, who did not grow up with technology, and do not understand it. And the questions they ask show that, to them, it’s either irrelevant, or a magic box, or whatever. And this idea of who in society gets the power, who in society gets to decide what’s good and what’s bad, and, in my experience, why is it always people older than me? Why am I 42 years old, and I still see people in politics who are older than me? It feels like at a certain point, the next generation takes the reins of power. So, yeah, that idea of who gets the power and who gets to wield it I thought was interesting and relevant.

Henderson: I think it’s difficult to say whether or not we’re pushing towards nostalgia, or if it’s just a capitalist decision to be, like, “You know what sold? Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles.” And I like them, but damn it, I want to see something else. And it’s not so much that people are pushing this as much as someone saying, “I don’t want to take a chance.” And that’s no way to live.

North: I’m obviously as vulnerable to nostalgia as anyone else. I’ve invested my entire life in watching Star Treks, and I will continue to watch Star Treks, because I just enjoy Star Treks. I think that’s almost human nature: you find something you like, you want to see more of that. But I would hate if the children who are teenagers today grow up, start creating art that gets published, and it’s the exact same stuff that we’re doing, right? I think it would be a loss of potential if we kept telling ourselves the same story over and over. I mean, I love variations on a theme — Dinosaur Comics is 20 years into variations on a theme — but there’s so much room for new stories. Again, I also love Ninja Turtles, but I don’t want all of culture to be Ninja Turtles.

Henderson: When you’re doing work for Marvel or DC, those are characters who have largely been there for 80 years. I don’t want to dismiss it, but I don’t want it to be the only thing. It breaks my heart, honestly, when people describe themselves as content creators, because the word “content” is a fungible fluid to fill someone else’s vessel: “I make the thing that you sell.” And there’s so much more to telling a story or creating art than creating content. It’s the most dismissive, capitalist way to describe anything. You’re not a person, you’re a taxpayer. You’re a consumer. It’s a tiny slice of what you do, but it’s being sold as an identity.

io9: So do you feel like the future of being able to do these original stories, like you’ve done here, is in original graphic novels? Is there a way to put out a story like Danger and Other Unknown Risks as a monthly comic?

Henderson: I think — and it sucks to say this — I think you have to already be famous to do something like [the Kieron Gillen and Jamie McKelvie series] The Wicked + The Divine. That was a legitimate hit, but would people have started picking it up right away had those creators not already proven themselves? And there are flukes. The Walking Dead was a fluke. But it’s rare when these things happen, and it does help to already be known.

I think that’s the trajectory that a lot of people, and I’m including myself in this, have strived for. It’s like, “OK, I’ve gotten in, I’m in the machine. I’ve made it. I just need enough people to know my name so I can now do other things.” Because it’s kind of the only way. You have to get yourself out there, which with the internet is easier at this point. There are people who are making their name purely online and then getting into publishing, which is really cool.

io9: Now that this book is out and done with, where do the two of you go from here?

North: Erica will tell me if I’m wrong, but I think we both had a great time doing this book. Who knows where we’ll be in a year, but I feel like the creative relationship with Erica has been great, and I don’t want it to stop yet.

Henderson: Yeah, I would agree with that. Also, I just finished a graphic novel with Alex De Campi that will be out this October called Parasocial, and I’m currently talking with TKO. So we’re constantly hustling, which is the nature of this industry.

Danger and Other Unknown Risks from creators Ryan North and Erica Henderson is out now.