Astronomers have seen the most energetic cosmic explosion yet, which they believe resulted from a gas cloud being disrupted by a supermassive black hole.

The explosion (dubbed AT2021lwx) happened billions of light-years away and was first spotted in 2020. But now it’s lasted over three years, indicating the sheer amount of material involved in the event. The team’s research describing the explosion was published today in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

“Once you know the distance to the object and how bright it appears to us, you can calculate the brightness of the object at its source,” said Sebastian Hönig, an astronomer at the University of Southampton and a co-author of the paper, in a university release. “Once we’d performed those calculations, we realised this is extremely bright.”

The gargantuan explosion dwarfs that of the BOAT (or the Brightest of All Time), a gamma-ray burst spotted last year. The BOAT is still the brightest-known explosion, but it was fleeting compared to the multi-year outburst of AT2021lwx.

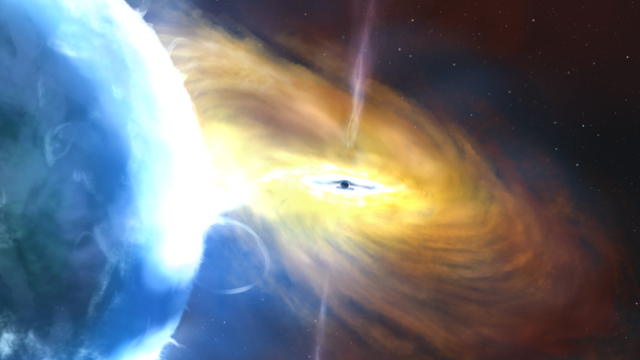

The explosion is as bright as a quasar — an active galactic nucleus with a supermassive black hole at its core, which appears very bright in the sky. But unlike a quasar, AT2021lwx only recently appeared in the sky. The team believes the event was caused by the interactions between a cloud and a supermassive black hole.

Black holes are the densest objects in the universe. Their gravitational pull is so immense that not even light can escape their event horizons. Once merely the realm of theory (the enigmatic objects were first predicted by Einstein), black hole shadows have since been imaged by massive radio telescopes, clueing researchers in to details of their extreme physics.

The recent astronomical team thinks the explosion was caused by wayward gas (or dust) from a cloud orbiting the black hole, which fell into the superdense object. From our perspective, the material is still falling into the black hole, but the explosion happened nearly 8 billion years ago.

“With new facilities, like the Vera Rubin Observatory’s Legacy Survey of Space and Time, coming online in the next few years, we are hoping to discover more events like this and learn more about them,” said Philip Wiseman, also an astronomer at the University of Southampton and the paper’s lead author, in the same release. “It could be that these events, although extremely rare, are so energetic that they are key processes to how the centres of galaxies change over time.”

The Legacy Survey of Space and Time will make use of the world’s largest digital camera to image the night sky every 15 seconds, giving astronomers around the world a newly dynamic view of a constantly changing universe.

The team plans to collect X-ray data on the explosion, among other wavelengths of light, to better understand the origins of the gargantuan blast.