Open your kitchen drawer and take out some tin foil. Twirl it into a cone – maybe even double-wrap it – and put it on your noggin. Do you feel safer yet? The tin foil hat is perhaps the most iconic headgear for conspiracy theorists. Wearing one signals to others that you’re unhinged, have a deep distrust of the government, or that you’re really worried about aliens. To some, it’s an alleged way to block a centralized power’s electromagnetic waves from entering your brain. But does it work?

Origins of the Myth

The tin-foil hat can be traced back to 1927, first spotted by Business Insider roughly a decade ago, in a short story titled “The Tissue-Culture King.” It’s a strange short story written by Julian Huxley, whose brother Alduous was a prolific writer and author of Brave New World. It was Julian, however, who was possibly the first to mention wrapping your cranium in foil.

In the story, a scientist called Hascombe gets lost in a jungle and is captured by a local tribe. He ultimately starts practicing mass mind control, eventually using it on the tribe’s king to coordinate his escape. But how does Hascombe avoid having his mind controlled? It reads:

Well, we had discovered that metal was relatively impervious to the telepathic effect, and had prepared for ourselves a sort of tin pulpit, behind which we could stand while conducting experiments. This, combined with caps of metal foil, enormously reduced the effects on ourselves… We with our metal coverings were immune.

As Vice notes, the story ends on a somewhat conspiratorial note, asking the reader whether they’re one of “those who labor because they like power, or because they want to find the truth about how things work.” As we approach the 100-year anniversary of the tin foil hat, the story’s sentiment still feels relevant to many conspiracy theorists today, offering a generally paranoid and skeptical worldview.

Even though “tin foil hat” is the expression, most people use aluminum foil these days. The U.S. Foil Company (the parent of Reynolds) first introduced aluminum foil in 1926, and it almost immediately replaced all tin foil on supermarket shelves around the country. Aluminum was thinner, lighter, and ultimately better for wrapping food. Brain protection, however, doesn’t seem to have been a factor in the switch though.

So, uh, Does It Work?

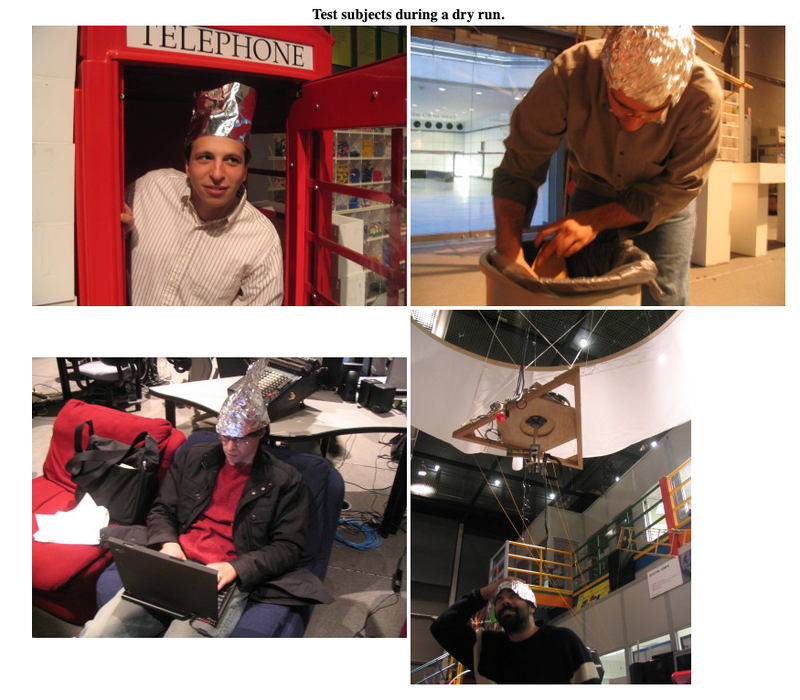

There have been relatively few experiments done on the true effectiveness of tin foil hats – most likely because of their ridiculous premise – but the question remains. Could a hat of foil block electromagnetic waves from touching your brain? The idea is that the metal acts as a Faraday cage, which blocks certain wavelengths from passing through. In 2005, a group of four cheeky MIT graduate students set out to answer the question with, “On the Effectiveness of Aluminium Foil Helmets: An Empirical Study.”

“One afternoon, we had a really stupid idea,” Benjamin Recht, one of the four authors of the MIT study, said in an interview with Gizmodo. “We were in a lab with very expensive equipment and just decided to use that, like, $US200,000 piece of equipment to test whether or not aluminum foil hats prevented radio waves from going in.”

Recht went on to be a Professor of Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences at the University of California, Berkeley. When Gizmodo reached Recht’s former professor at MIT in 2005, who oversaw the lab the experiment took place in, he emailed back, “That was a joke, which got taken surprisingly seriously.” In the jokey study, the authors say:

It has long been suspected that the government has been using satellites to read and control the minds of certain citizens. The use of aluminum helmets has been a common guerrilla tactic against the government’s invasive tactics [1]. Surprisingly, these helmets can in fact help the government spy on citizens by amplifying certain key frequency ranges reserved for government use. In addition, none of the three helmets we analyzed provided significant attenuation to most frequency bands.

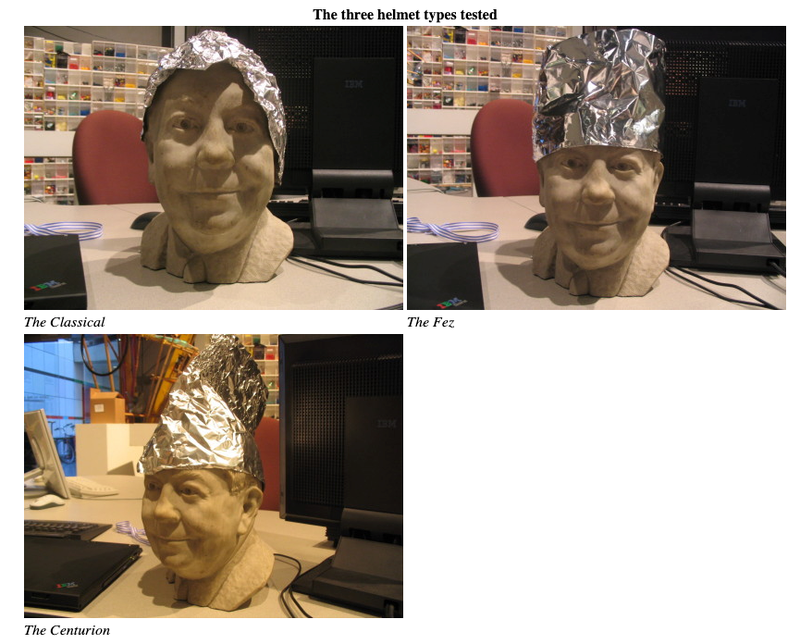

Recht says the study shouldn’t be given any credibility and was mostly a joke at the expense of anyone who wears these helmets. Nevertheless, they wrote that tin foil hats were ineffective at blocking most wavelengths. They genuinely did test three helmet types: The Classical, The Fez, and the Centurion. The authors even offer their own conspiracy theory, writing about how tin foil hats amplify certain waves reserved for government communications:

The helmets amplify frequency bands that coincide with those allocated to the US government between 1.2 Ghz and 1.4 Ghz. According to the FCC, These bands are supposedly reserved for ‘’radio location’’ (ie, GPS), and other communications with satellites (see, for example, [3]). The 2.6 Ghz band coincides with mobile phone technology. Though not affiliated by government, these bands are at the hands of multinational corporations.

It requires no stretch of the imagination to conclude that the current helmet craze is likely to have been propagated by the Government, possibly with the involvement of the FCC. We hope this report will encourage the paranoid community to develop improved helmet designs to avoid falling prey to these shortcomings.

Though it wasn’t exactly clear to everyone that this was a joke, Recht notes how this paper went viral at the time. It first popped up on Slashdot, which he describes as the Hacker News of its day. Years later, The Atlantic wrote up the study. But the story has continued to pop up in strange places over the years, as often happens when people engage with conspiracy theories.

“It was a weird thing that kind of took on a weird life of its own,” Recht said, noting how some tin foil hat wearers may have taken the experiment a little too seriously. “We got some weird emails and… there are people out there who definitely have opinions and access to computers, and they definitely sent us some thoughts. So, you know, it’s definitely real all the popular conspiracies people buy into.”

While Recht can’t vouch for the study, it seems likely that tin and aluminum foil hats are not effective Faraday cages. As Dr. Michelle Dickenson points out, Faraday cages need to fully surround the items they protect. Because a foil hat only covers the top of your head, it leaves a lot of room for electromagnetic waves to get in through the bottom. Before you go wrapping your entire head in foil, remember that even in a perfect lab environment, Faraday cages can be difficult to create.

Why It’s Pervasive

Since 1926, conspiracy theories have only grown more intense throughout society. The emergence of 5G towers has fueled a newfound fear of electromagnetic radiation, spurring a resurgence in modern products promising Faraday cage abilities to protect people from the so-called dangers. These include 5G blocking beanies and hats, which seem like a modern-day tin-foil hat that promises protection without the ridicule. Ranging anywhere from $US30 to $US65, these are much more expensive than the aluminum foil in your kitchen drawer.

The internet is great at propping up conspiracies like this. Message rooms and Facebook groups become echo chambers for outlandish ideas. The tin foil hat may be an extreme version of this, but it happens in small bursts all the time. In the last few months, cell outages, the Baltimore Key Bridge collapse, and a solar eclipse have spurred fresh crops of conspiracies for the internet to feast on. They all center around a collective distrust of what the media and government say.

But the truth is, there’s really no evidence that a centralized power is trying to control your brain through electromagnetic waves entering your brain stem. If you really want to protect your brain from being controlled by a centralized power, it might do you much better to get off your devices and social media. The electromagnetic waves radiating from those conspiracy channels seem to be doing more harm than anything else.