We’ve all had that moment while perusing a flea market or junk store when you stumble across an item and have to yelp, “Good lord, that is ugly!” So ugly, in fact, you have to marvel that it even got made in the first place.

But what is it exactly that makes an object ugly? Picture a Rococo room, with every inch covered in scrolling gold ornamentation, crammed with chubby cherubs and vaguely erotic irregular shapes. Do you feel horrified or fascinated? Compare that with the spare, clean lines of Shaker room with simple, elegant wooden furniture. Is it the picture of blissful peace or painful boredom? Does folk art make you cringe, or do you see rough-hewn beauty in its imperfections? Does iridescent carnival glass make you jump for joy or avert your eyes?

You might feel revolted by an object, but if you try to objectively explain why it is ugly, it’s harder than you think. Most people are influenced by the dominant tastes and fashion sensibilities of their generation, class, and ethnic group, and when you remove those factors from the equation, an exact, universal definition of “ugliness” becomes almost impossible to pin down.

Top: The basilica at Ottobeuren Abbey in Germany was built in ornate Rococo style in the 18th century. (Photo by Johannes Böckh & Thomas Mirtsch, via WikiCommons) Above: These folk-art automatons, hand-carved in the 1930s, represent Popeye and Olive Oyl’s date night.

British design critic and cultural commentator Stephen Bayley was up for the challenge, writing a book called Ugly: The Aesthetics of Everything, first published in 2012. But as Bayley — who is unapologetically obsessed with his Modernist version of beauty — delved into the process of examining what he and others consider ugly, he found that the ugliness would vanish.

Still, everyone has an intuitive sense of ugliness — things we find troubling, aggressive, or annoying — and we know it when we see it. “We all know what ugly really means,” Bayley says. “The English word comes the Old Norse word, ‘uggligr,’ which means ‘aggressive,’ which is why we talk about an ‘ugly customer’ in English. Ugly things are things which we find disturbing. But at the same time, disturbing things are also interesting.”

Ugliness is also surprisingly hard to design on purpose, as Bayley discovered both teaching and speaking with architecture students. “If you give a class of architecture students a project, saying ‘Please design an ugly building,’ they actually find that difficult. It’s very difficult to create ugliness, although you wouldn’t believe it by walking around in any big city. Ugliness often is just an accident, but it’s often utterly fascinating.”

Bayley explains that researchers studying “neuro-aesthetics,” which he calls “this new almost pseudo-science,” are attempting to map the human brain’s response to what’s lovely and what’s repulsive. But scientists have been attempting to quantify beauty for ages.

This 1960s Danish Modern teak desk and a new iPhone embody Stephen Bayley’s ideals of beautiful design.

As far as we know, ancient Greek mathematicians like Pythagoras and Euclid were the first to calculate what’s known as the Golden Ratio, an aesthetically pleasing pattern found often in nature. Centuries later, a medieval Italian mathematician named Leonard Fibonacci gave the ratio a numerical sequence. It’s found in the petals and seed heads of flowers, in pinecones and pineapples, in tree branches, nautilus shells, spiral galaxies, human faces, animal bodies, and DNA sequences. It’s also the basis of classic Greek and Renaissance architecture.

Paradoxically, if every single thing in the world were flawless and perfectly proportioned, humans would be miserable. In fact, too much perfection can even be disturbing, as scientists discovered when they introduced people to humanoid robots too flawless to be real people. The theory of the “uncanny valley” explains why people are revolted by simulations that are “almost human” but not quite. Similarly, Bayley finds ugliness absolutely necessary.

These 1940s “feature matches” are violent, racist, and decorated beyond function. (Photos by Frank Kelsey)

“We need variety and we need strife. We need aesthetic conflict. In this sense, ugliness may be a very good thing. We need a certain measure of ugliness in order to enjoy the beautiful. But how much ugliness do we need? Should 30 per cent of the world be ugly, or 40 per cent? I don’t know.”

In his book, which Bayley says is slightly tongue-in-cheek, he reiterates this complaint that the democratization of consumption meant that objects were made to attract the broadest consumer base possible, by appealing to the lowest common denominator — the same criticism social critics have launched at television programming for decades.

“Before industrial production, only the very rich could buy discretionary goods. Everybody else subsisted on craft production,” Bayley explains. “But the Industrial Revolution turned everybody into consumers, and everything became an episode in the history of taste. Bernard Berenson, the great art historian, once said that taste begins when the appetite is satisfied. And that’s what happened, really, in the 19th century to a very large degree: The appetites of these new consumers were satisfied.

A 1930s photo Walter Potter’s “Rabbit School” diorama, when it was still on display at his Bramber, Sussex, museum. Potter was an early amateur taxidermist who created dioramas of animals doing human activities in the mid-1800s. (Via Wikipedia, Creative Commons licence)

And so, middle-class Victorians filled up their homes with knick-knacks and “conversation pieces” like art glass paperweights, which, Bayley writes, “represent in miniature the nineteenth-century attitude to design: at once marvels of the industry, but also aesthetic horrors. … If the public had a morbid appetite for the marvellous, then the industrialist and entrepreneurs who manufactured paperweights were well able to stimulate and satisfy it.”

Expectant mothers often used stork-shaped objects like these embroidery scissors. Stork-shaped clamps were even used to cut umbilical cords.

Victorians were well aware of their own excesses and ridiculousness. In 1852, Henry Cole, the founder and director of the institution that became known as the Victoria and Albert Museum, opened a Gallery of False Principles demonstrating bad design, which came to be known as the extremely popular “chamber of horrors.” In a 2001 article in the Guardian‘s magazine, Sarah Wise describes the collection containing things like a pink bottle shaped like a snake, a flower-pot shaped like reeds tied with a yellow ribbon, scissors shaped like a stork, a morning-glory shaped gas-jet lamp made of glass and gilt brass, a jug in the form of a tree trunk, a chintzy papier-mâché tray, and blindingly busy wallpaper.

In Germany, museum curator Gustav E. Pazaurek followed in Cole’s footsteps, opening his “Cabinet of Bad Taste” at the Stuttgart State Crafts Museum in 1909 to demonstrate what he considered design mistakes. His catalogue of design offenses includes anything made of fur, bones, or teeth; animal trophies; material used to imitate other materials; mass-produced objects aping handcrafted ones; manic ornamentation; lies of function; odd proportions; sharp edges; excessive iridescence; anachronisms; design imitating foreign cultures; fake folk art; jingoistic, religious, racist, or sexist kitsch; and toys that harm children.

The morning glory gas-jet lamp found in Henry Cole’s “chamber of horrors.”

To rid the Machine Age of all this bad design, the first waves of Mid-Century Modernism arrived as the Bauhaus school in 1919 and as Art Deco, or Streamline Moderne, in 1925. This time, the elite, educated world of design would beautify and simplify common mass-produced consumer objects, offering the unwashed public top-down taste, through lovely and uncomplicated things such as Catalin radios and Bauhaus chairs.

“Mass-produced stuff doesn’t have to be ugly,” Bayley says. “Mass production requires standards, and standards lead to excellence, or so Le Corbusier believed. Mass production frequently leads to elegant and pleasing solutions. That’s the whole story about the adventure of Modern design. It was meant to make beauty commonplace and democratic. That’s a wonderful idea.”

For example, iconic designer Raymond Loewy even transformed household machines, such as the Coldspot refrigerator, Coke dispenser, and Singer vacuum cleaner, into chrome-trimmed works of art during the 1940s and ’50s. In 1956, according to Ugly, Dieter Rams reached the apex of Modern idealism with the radio-turntable dubbed “Snow White’s Coffin.”

Dieter Rams’ 1956 SK4 Braun radio, called “Snow White’s Coffin,” is Modernist perfection in Bayley’s eyes. (From “Ugly,” courtesy of Wright)

In the 1950s and ’60s, the sleek, efficient, and futurist look of Mid-Century Modern was absorbed into corporate culture, as it dominated offices adorned with Knoll furniture. Buildings made in the Modernist subset known as Brutalism — so named after the French phrasebeton brut, meaning “raw concrete” — were heavy, large, imposing things with jutting angles that look appalling to people now.

“Most people do find Brutalism unattractive today,” Bayley concedes. “But in England, there’s a change of taste. That’s why I put England’s most famous Brutalist building, the Trellick Tower in West London, on the back jacket of my book. It’s recently been listed by English Heritage as a building of national historic architectural importance. Any minute now, I promise you, Prince Charles, who used to condemn these things, will be telling us that Trellick Tower is a thing of beauty.”

The Trellick Tower in London, commissioned in 1966 and completed in 1972, is being recognised for its historical significance as an example of Brutalist architecture. (Via WikiCommons)

In Ugly, Bayley names a few of his worst offenders from their book’s content page, including novelties and gags; Aloha shirts; bobbleheads; Tupperware; artificial Christmas trees; tattoos; Troll dolls; polyester; Day-Glo; macramé; pet clothing; shag rugs; snowglobes; reclining chairs; and candle art.

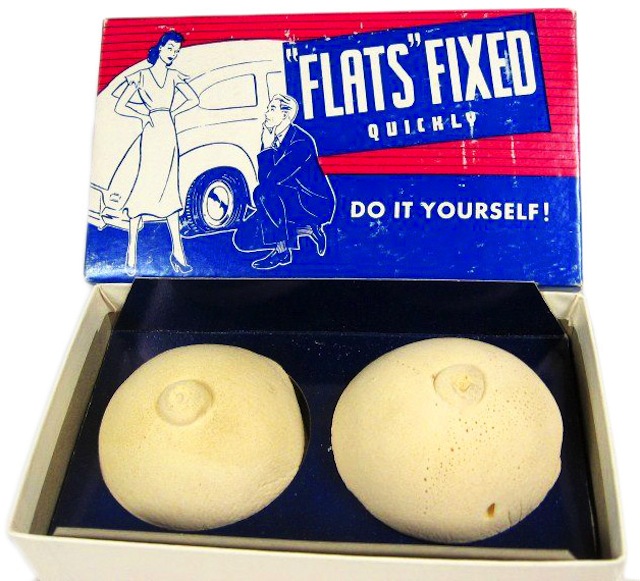

One list item, “Breasts (enormous)” seems like body-shaming, until you realise the Sterns are not talking about living, breathing women themselves. Instead, they’re referring to the U.S.’s national obsession with objectifying big breasts by depicting them on actual inanimate objects from Barbie dolls to girlie glasses and beach souvenir mugs shaped like disembodied boobs. Certain car bumpers were even crassly dubbed Dagmars, because they resembled the ample bust line of a 1950s actress Virginia Ruth Dagmar. All this unseemly and sexist leering makes people in the elite design world cringe. But at the same time, they consider it tasteful and not at all gratuitous these days to expose small breasts on runaways and in fashion shoots, what some critics have dubbed “fashion tits.”

This cruel gag box from the 1950s highlights America’s obsession with objectifying large breasts. (Courtesy of Mardi and Stan Timm)

Today, Apple products like iPhones, iPads, and MacBooks embody Bayley’s ideals of elegant and functional design, but, he says, Apple will soon have no choice but to make them more gaudy. “Apple’s run out of ideas aesthetically,” he explains. “You can’t make anything more pure than the current iPhone or iPad. They’re going to have to go Baroque — which they have already started to do. You see it with their new products, like the iPhones in bright colours. Their English senior vice president of design, Jonathan Ive, is a brilliant guy. What he’s doing is ultra-sophisticated. He created these technologically dense products using a craftsman’s technique and skills because his father’s a silversmith and he actually knows how metal works. These lovely things in our hands are only apparently simple. They’re in fact extraordinary. They’re not utilitarian at all, but incredibly subtle and contrived. I promise you, in five years’ time, they will be very different.”

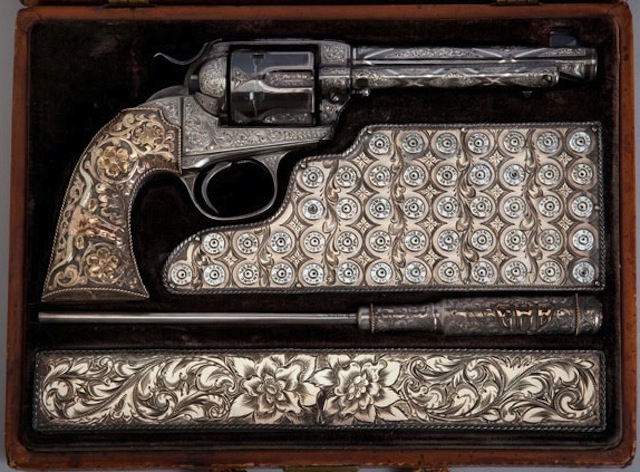

Writing Ugly, Bayley ran smack into another contradiction: If good, functional design with clean lines telegraphs high morals, then what about the Colt .45, “the gun that won the West,” which functions excellently? Many beautiful, astounding objects have been designs for “ugly” purposes, such as death, war, and mass destruction. Colt .45s and other machine-made guns in the 1800s were sometimes embellished — plated in gold or silver and hand-engraved with intricate designs.

Saddlemaker Edward H. Bohlin owned this cased Single Action Army Revolver, manufactured by Colt’s Patent Fire Arms Manufacturing Company, circa 1903. He engraved it himself, and Gene Autry eventually bought this gun. (Courtesy of the Autry National Center)

“Again, I’m undermining some of the assumptions of the Modernist movement, which said anything well-designed would be beautiful,” Bayley says. “That’s clearly not true, because a lot of things which work very well like oil refineries, few people find them beautiful. Equally, with things like guns and military aircraft, lots of people would agree that they’re beautiful, but then they have a functional purpose which most people find repellant. That’s why I wrote the little chapter about the B-52. What an amazing machine. It’s awe-inspiring, the technical mastery it suggests. I personally find it a physically beautiful thing as well, with lovely shapes and details. But this beautifully designed machine was created in order to cause destruction. What sort of beauty is that?”

Perhaps truth is not beauty, after all.

(To read more, pick up Stephen Bayley’s “Ugly: The Aesthetics of Everything” at Overlook Press. Find more of Bayley’s books at his web site.)

Related Links:

- Velvet Underdogs: In Praise of the Paintings the Art World Loves to Hate

- Taxidermy Comes Alive! On the Web, the Silver Screen, and in Your Living Room

- Style Gone Wild: Why We Can’t Shake the 1970s

- How Your Grandpa Got His LOLs

- Kem Weber: The Mid-Century Modern Designer Who Paved the Way for IKEA

This article has been excerpted with permission from Collectors Weekly. To read in its entirety, head here.

To subscribe to updates from Collectors Weekly, you can like them on Facebook here or follow them on Twitter here.