Many good sea tales begin with a fisherman snagging his net on an underwater object, and this tale is no different. In 2000 or 2001, fisherman snagged his net while fishing the waters of Goodwin Sands, fronting the White Cliffs of Dover near the town of Deal in Kent, England. Dover sits at the English Channel’s narrowest point, and faces Calais, France.

This area took the brunt of the fighting during the Battle of Britain (July 10 — September 6, 1940) and the ensuing Blitz on London and surrounding cities (September 7, 1940 — May 21, 1941). Kent was known as “Hell Fire Corner” for the amount of destruction that rained down on the area during the battles.

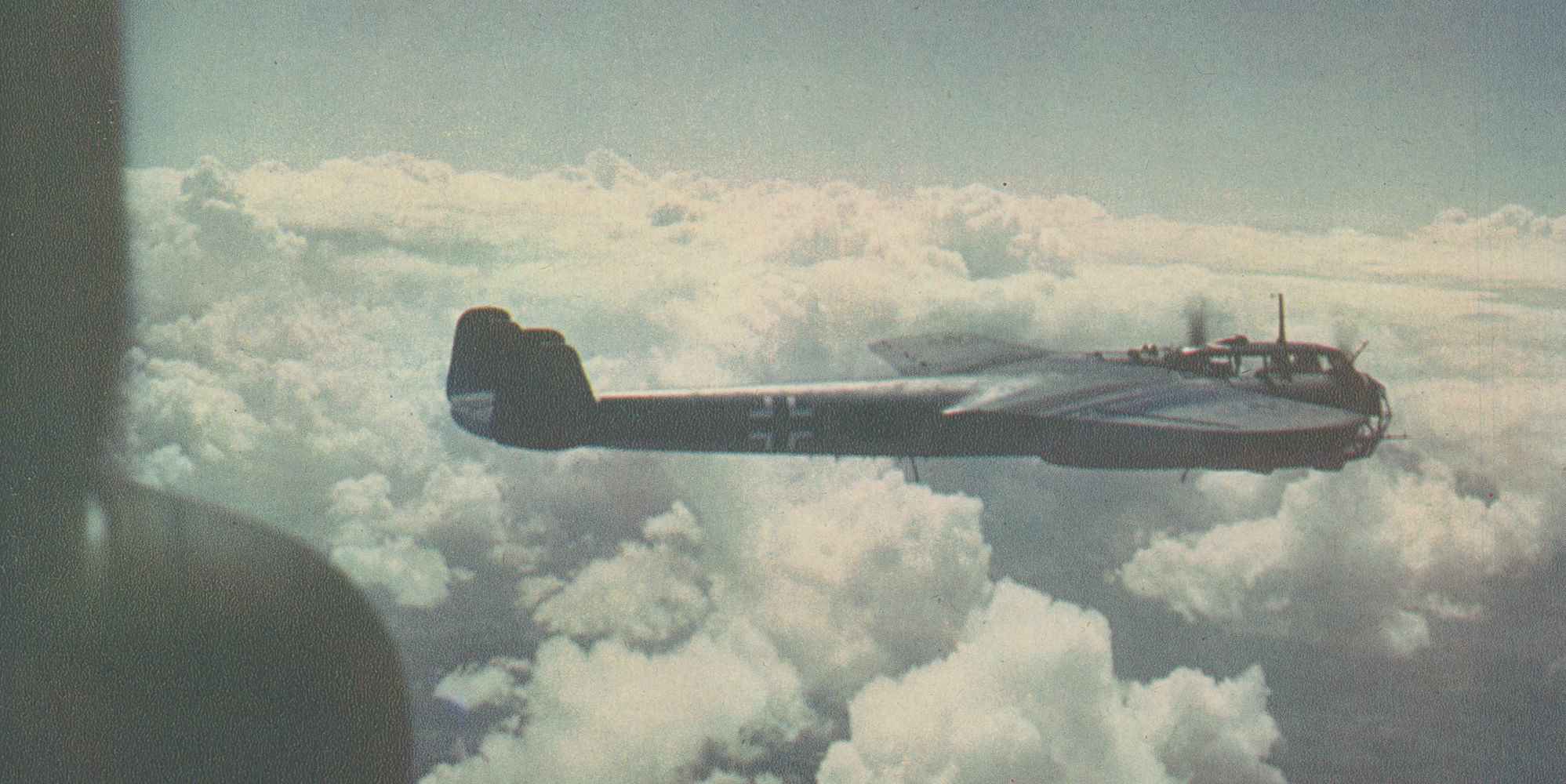

Rare colour image of a Do 17Z in flight. More than 1500 examples of the “Flying Pencil” were built, and more than 400 attacked England during the Battle of Britain and the subsequent Blitz on London. The Do-17Z-2 (fuselage code 5K+AR) was shot down on August 26, 1940, and ditched off the coast of Dover. Courtesy RAF Museum

Estimates put the number of shipwrecks in this area of the English Channel at more than two thousand. To illustrate the point, the area was the site of two major naval battles during World War I: the First Battle of Dover Strait (October 26 — 27, 1916, when German forces were victorious over the British), and the Second Battle of Dover Strait (April 20 — 21, 1917, a British victory).

Because of the area’s huge number of sunken ships, most in the fishing community were not surprised when the nets were snagged and subsequently repaired, and the incident was soon forgotten. In 2004, sport scuba diver Bob Peacock learned of the wreck’s location, but it was another four years, until September 2008, before he made the journey to look for the snag. Lying almost four miles off the coast, the bottom topology is a chalk bed, between fifty and eighty feet deep covered by shifting sands. Underwater visibility in the area ranges from twenty five feet on the best day, to nearly zero when the tides are running.

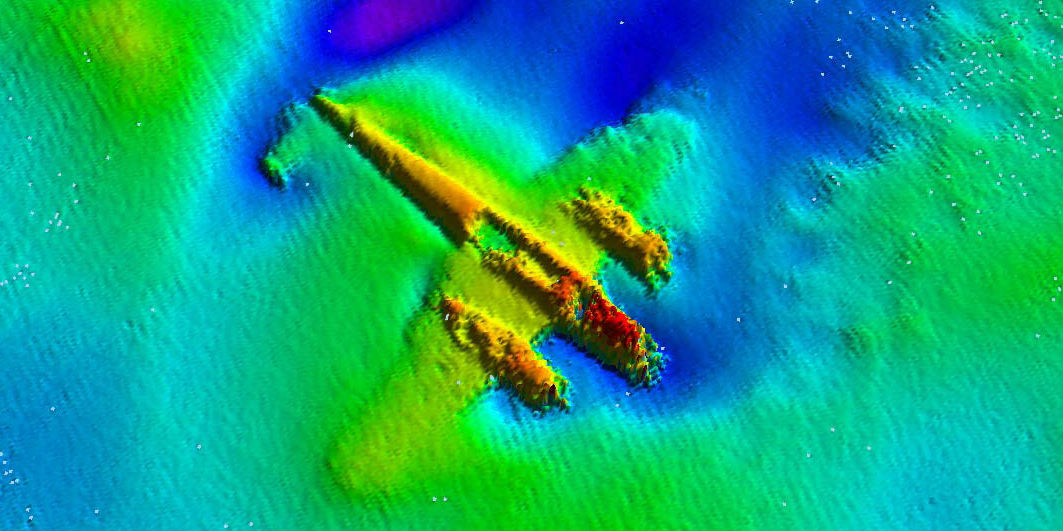

Side-scan sonar image of the Do-17Z prior to recovery by the Royal Air Force Museum. The scan shows the Do-17 resting inverted on the bottom of the English Channel. The aircraft was ditched into the sea, and then turned upside down during its descent to the bottom of the channel. From this scan, it can easily be determined that the starboard horizontal tail and the bomb bay doors are missing. Port of London Authority

Instead of a shipwreck, Peacock found an aircraft partially buried in the sand. Peacock reported his find, and Wessex Archaeology of Salisbury, England, was given the task of surveying the crash site. In May and June 2009, Wessex Archaeology found a twin-engine aircraft lying inverted, nearly complete, fifty feet below the surface. Around the aircraft was a debris field, but a number of parts were missing, including the starboard horizontal and vertical tail, tail cone and tailwheel, flaps, engine cowlings, bomb bay doors, main landing gear doors, and the cockpit canopy.

From a small number of parts recovered from the wreck in 2009, researchers from the RAF Museum, Hendon, England, were able to determine that the wreck is that of a Dornier Do-17-Z2 — the only substantially complete example of its type known to exist. The Do 17Z was a light, fast bomber, referred to as the Fliegender Bleistif or “Flying Pencil.” There were more than 1,500 Do-17s built between 1934 and 1944, and more than 400 were used against the British during the Battle of Britain. The Germans lost more than 200 Do-17s to all causes during the Battle of Britain and subsequent Blitz.

On June 11, 2013, the Do-17Z was raised from the sea in an area known as Goodwin Sands, approximately four miles from the English coast.

Divers attached lifting straps to the aircraft and it was raised from the bottom and lifted onto a barge. Courtesy RAF Museum.

RAF Museum researcher Andrew Simpson compiled the Do-17Z’s history, believing the aircraft to be Werke no. 1160 that was based with 7 Staffel, III/KG3 (7 Staffel or Squadron, 3rd Group, Kampfgeschwaderor Bomber Wing 3). At the beginning of the Battle of Britain, KG 3 had 108 bombers on strength, of which 88 were combat ready. The unit was based at St. Trond, Belgium, and on August 26, 1940, Werkeno. 1160, wearing the fuselage codes 5K+AR, was part of a squadron sent to bomb the RAF airfields at Debden and Hornchurch, more than sixty miles north and east of London. Flying above clouds, the Do-17 became separated from its squadron and turned south to get its bearings. The Do-17 was attacked by Boulton Paul Deants — low-wing, turret-equipped fighters — of No. 264 Squadron, based at RAF Hornchurch. Although accounts are conflicting, in the ensuing melee, seven Do-17s of the attack were shot down by the Deants.

It is assumed that Do-17 5K+AR made a run for the coast headed for Calais, France, because its crash location is some eighty miles south and east of the Germans’ intended target. A direct line back to St. Trond required a flight of more than two hundred miles, while Calais, or the narrow channel area between Dover and Calais, afforded a better chance of survival for a bomber trying to limp home, short of fuel. If the Do-17’s crew had to ditch, they stood a greater chance of being picked up by German crash boats patrolling in the vicinity.

Marine growth covers every square inch of the German bomber. In spite of how bad it looks in this view, the growth helped preserve many parts. Courtesy RAF Museum

Hit by fire from the RAF Deants, 5K+AR ditched in the Channel, less than four miles off the English coast, not far enough across to hope for rescue by the Germans. Pilot Feldwebel Willi Effmert, and bombardier Unterozier Hermann Ritzel were both wounded in the air battle. After the aircraft ditched, they were rescued by the British and became prisoners-of-war in Canada. Wireless operator Uffz. Helmut Reinhardt and bombardier Gefreiter Heinz Huhn were killed. Their bodies subsequently washed ashore on opposite sides of the Channel with Reinhardt interred in Holland and Huhn buried in England. While the pilot and bombardier were being rescued, Do-17Z-2 5K+AR slid beneath the English Channel, landing inverted on the bottom.

Recovery Operation

In June 2010, another series of dives were made to access the condition of the wreck and to plan for the Do-17Z’s recovery. The plan involved lifting the entire wreck in one piece through a cage system. Having determined a positive potential for recovery, the project to recover the sole surviving Flying Pencil began to move forward.

“The discovery and recovery of the Dornier is of national and international importance. The aircraft is a unique and unprecedented survivor from the Battle of Britain and the Blitz,” said Air Vice- Marshal Peter Dye, director general of the RAF Museum.

The recovery operation received more than £345,000 ($538,000) from Britain’s National Heritage Memorial Fund and the project got underway. The RAF Museum served as manager of the recovery project with assistance from Seatech Commercial Diving Services, the Port of London Authority, and researchers from Imperial College, London, who are serving as conservation consultants. Additional funding was provided by WarGaming.net, 328 Support Services GmbH, the EADS aerospace consortium (of which Dornier is a legacy company), the Society of Friends of the RAF Museum, and the general public.

Manufacturer’s dataplate as found on the Do-17Z, seen shortly after recovery.Courtesy RAF Museum

With everything in place, the RAF Museum and Seatech team began operations in May 2013. Poor weather in the Channel forced the team to abort recovery attempts and return to port four times. With so many aborts, the RAF Museum decided to abandon the cage recovery system in favour of attaching lifting rigs directly to the aircraft. Divers worked in teams, and were only able to stay down for forty minutes at a time rigging the new lift system. The new rigging would enable a seagoing crane to make one li of the bomber, from the bottom of the sea up and onto the deck of a barge.

On the eve of the li, June 2, 2013, RAF Museum Director Dye said, “We have adapted the lifting frame design to minimize the loads on the airframe during the lift while allowing the recovery to occur within the limited time remaining. The RAF Museum has worked extremely closely with Seatech throughout this process and both organisations remain determined to complete this challenging task and see the Dornier safely recovered as planned.” Unfortunately, the winds did not favour the recovery attempt on June 2, and the crew watched the weather, waiting for a new opportunity.

On June 10, the winds died down, the seas calmed, and the RAF Museum and Seatech team was able to make a successful lift. After a long day of dedicated work, the Do 17Z was brought up on deck at 6:30 p.m. local time. The main landing gear tires were still inflated and the propellers, recovered separately, were curved, showing that they were turning under power when the bomber ditched.

Once on deck, any hazardous materials were addressed and the Do-17’s MG 15 machine guns and magazines were secured for later inspection. When safely back on the dock, the magazines were x-rayed, only to be found empty — a vivid reminder of the back-and-forth air battle fought in the skies over Kent.

During the five-hour trip from the recovery site to the dock at Ramsgate Harbor, the RAF Museum team went to work removing the bomber’s wings and horizontal tail. After they had cleared seventy- three years of marine growth, the attach bolts were easily removed. The fuselage, wings, and tail were put into a frame for the loading and transport of the German bomber to the RAF Museum at Cosford for conservation. As the frame was being built around the bomber’s components, a gel was sprayed and brushed onto the aircraft to keep oxygen from continuing to corrode the metal.

The aircraft was driven more than two hundred miles on a flatbed trucks to the Michael Beetham Conservation Center at Cosford. Once at the museum, the aircraft components were unloaded and placed into two hydration tunnels, essentially large greenhouse-like structures, where they are repeatedly sprayed with citric acid as the first step in conserving the aircraft. In addition to inhibiting corrosion, the citric acid helps soften the layers of marine growth, enabling further corrosion-inhibiting efforts. As the marine growth becomes loose, conservation staff uses plastic scrapers to peel back the sea slime.

The fuselage was lifted from the sea in its inverted position, and was transported in the same orientation. Courtesy RAF Museum

The conservation process is expected to take two years. To engage guests to the RAF Cosford Museum while the aircraft is conserved, a visitors’ center and an education center will enable the Dornier to be seen up close while in the hydration tunnels. An RAF Museum spokesman said that displays “at the Cosford and Hendon Sites will ‘taxi’ the aircraft virtually through the wall and at the Hendon site the aircraft will be raised through the ‘sea’ of carpet. The nose windows will light up to form a projection-mapped screen and tell the story from the gunner’s seat. During this phase virtual Dorniers will appear and hover ominously above their external shadows. Visitors will be able to view and explore these augmented-reality, life-size 3D models though a mobile application on their smart phones.”

The RAF Museum is no stranger to recovering and preserving aircraft, having most notably recovered a Halifax Mk II in 1973 from Lake Hoklingen in Norway and a Hurricane Mk I retrieved from the Thames estuary. It is conceivable that the Do-17, when ready for display, will sit facing the Thames estuary-recovered Hurricane in a Battle of Britain display.

Dornier Do-17Z fuselage being placed into the hydration tunnels at the Michael Beetham Conservation Center at the RAF Museum, Cosford. The aircraft is sprayed with a citric acid to inhibit corrosion. The preservation process is expected to take more than two years. Courtesy RAF Museum

The Dornier Do-17Z “will provide an evocative and moving exhibit that will allow the museum to present the wider story of the Battle of Britain and highlight the sacrifices made by the young men of both air forces and from many nations. It is a project that has reconciliation and remembrance at its heart,” said RAF Museum Director General Dye.

Excerpted with permission from Hidden Warbirds II: More Epic Stories of Finding, Recovering, and Rebuilding WWII’s Lost Aircraft by Nicholas A. Veronico.