When I recently set out for the Pentagon’s R&D department, I instead found myself in front of a downtrodden shopping mall in Arlington, Virginia. I’d been navigating the old-fashioned way — with my eyes — but when I pulled out my smartphone there it was, clearly marked in the Google Maps app: DARPA.

It turns out that the unmarked spaceship of a structure that DARPA calls home is tucked neatly behind the Ballston Common Mall. When I eventually found the right entrance and stepped inside the lobby, everything suddenly felt familiar. The clean lines and shiny surfaces would look right at home at the office of any number of large tech companies I’ve visited. The metal detectors, however, would not. The security desk promptly snatching my smartphone away before I headed for the elevators would have also been out of place at most startups, whose executives are just as tethered to their devices as teenagers with bad Snapchat habits. Of course, most tech companies aren’t tasked with developing weapons of warfare, like super strong humanoid robots and drones that fly out of submarines.

DARPA does a lot more than build weapons, however. The same government agency that invented the internet and laid the groundwork for America’s thriving startup culture is now trying to act more like a startup itself. Put simply, DARPA is making smartphones battlefield-ready, so that soldiers can take full advantage of the same mobile technology that’s improved the lives of countless civilians in recent years.

For the military — a hulking institution riddled with red tape and bound by bureaucracy — this is no easy task. But a nimble team of developers and researchers at DARPA have spent the past few years laying the groundwork for an app ecosystem, called the Transformative Apps program, that could change the way the United States fights wars. You can sort of think of it like an app store for the military, where all of the offerings are designed to work in hyper-secure environments, and often without a reliable network connection. It’s harder than it sounds.

Why the Military Needs Smartphones

DARPA program manager Doran Michels walked out of the elevator with purpose, flanked by a public relations team and clutching what appeared to be his lunch in both hands. He wore his hair short and his smile wide. He almost didn’t break stride when we shook hands and turned to leave DARPA’s glistening headquarters. “We’re going offsite,” he told the security guards. I got my smartphone back.

As head of DARPA’s TransApp program, Doran’s been on the front lines of the military’s battle to apply the undeniable utility of consumer smartphone technology and adapt it for use by the tactical community. This is no small challenge, since the vast majority of soldiers still depend on brick-sized radios and paper maps to navigate the battlefield. However, it’s a challenge Doran couldn’t be more enthusiastic about spearheading.

“The smartphone is a big deal,” he told me as we walked past the shopping mall and towards another unmarked building. “I don’t know that we’ll ever completely grasp the implications of how we’re learning to access and share information. You know these are big, transformative things in human evolution.”

You hear that sort of thing all the time from startup founders convinced that their app or gadget is more disruptive than the next. But to hear a Department of Defence guy get fired up about the boundless horizons of the Android operating system and wax hopeful about Samsung’s rugged new smartphone was a new experience.

Doran went on to explain why the awesome technology that Silicon Valley sells to us normals simply won’t work for the tactical community, especially soldiers fighting in Afghanistan. These devices work mostly because the network they’re connected to also works. Take away that network — which the vast majority of combat troops don’t have access to — and you’re left with a really expensive calculator. Just think of how useless your smartphone is when you can’t get a signal. It’s like that all of the time for soldiers.

However, if you could build a secure network, one that troops could actually use in the most remote stretches of wilderness and the most war torn cities, even the simplest of smartphone functions would be tremendous tools not only for communicating but also for other simple tasks that are quickly complicated in battlefield scenarios. The ability to view and manipulate maps in real time, for instance, is clearly a step up from the existing paper-and-pencil approach on which many soldiers currently rely. And yes, of course, smartphones would also be great communication tools, especially compared to the old brick-sized radios soldiers now use.

So the Pentagon launched the Transformative Apps program under the DARPA umbrella. The TransApp mission, as stated on DARPA’s website, is to “develop a diverse array of militarily-relevant software applications using an innovative new development and acquisition process.” The hardware itself is basically the same as what everyday Americans are walking around with every day. The big difference comes in how they’re connected. Since civilian networks can’t be trusted, soldiers must constantly set up secure networks on the fly using a suite of radios and networking equipment. Accordingly, TransApp developed a system that soldiers could plug smartphones into and gain basic connectivity. The corresponding apps are also designed to maintain functionality, even when they go offline.

How Smartphones Work on the Battlefield

Doran told me the history of TransApp the way a proud father talks about his family. The program started in 2010 with a budget of nearly $US79 million over four years. (That’s not a lot of money for a military with a total budget of over half a trillion dollars.) TransApps saw its first action in 2011, when 3,000 systems were deployed in Afghanistan, where Doran says the program received overwhelmingly positive feedback. The Army troops that were testing the apps used a variety of different devices depending on the specific tasks, but Doran told me the military settled on consumer-ready smartphones, rather than going through the rigamarole of designing their own proprietary technology. All of the devices Doran showed me in the TransApps office were Samsung.

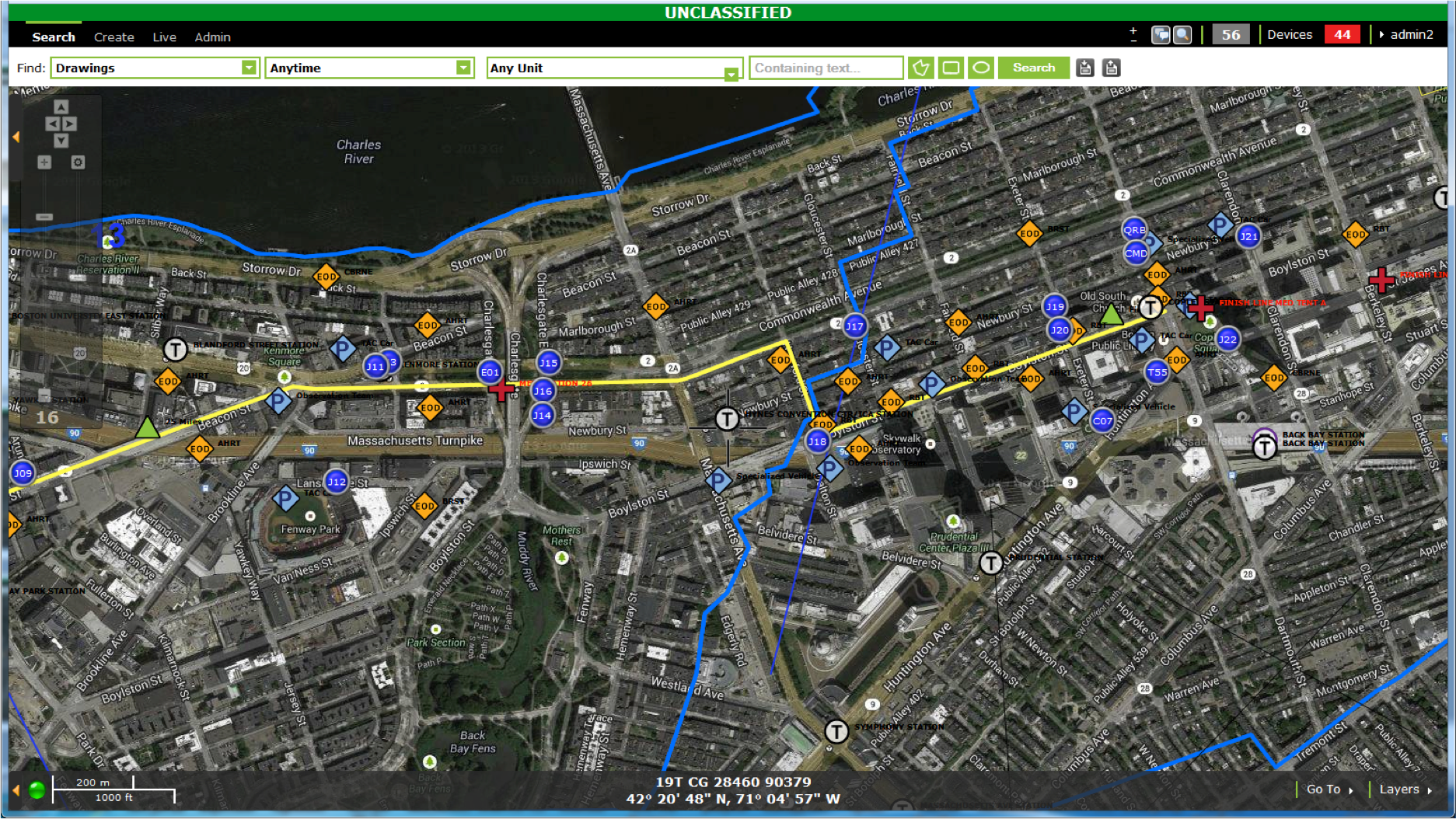

In the years since, TransApps has been used for everything from training soldiers to improving security at the Boston Marathon and Presidential Inauguration. Doran’s particularly proud of the integration in Boston a few months ago, since the high-profile event depends on the complicated coordination of several local and national agencies. Everyone from the FBI to the Boston Fire Department needed to know what everyone else is doing, and the same types of apps that keep soldiers organised in the battlefield worked perfectly there. You can see from a screenshot of the app they were using, where the specific units and checkpoints are located and how an officer in the field could search and sort for more granular information.

By the time Doran had finished the backstory, we’d left the sweltering heat outside and found our way into a curious office. The sign outside the door definitely did not say DARPA, though it’s unclear if that was intentional or not. It was some three-letter acronym, if I remember correctly, but the name was forgettable enough that I’m not sure I do. Inside, we turned right into a sizable conference room, where a mannequin stood guard in Army fatigues.

This was no ordinary set of fatigues, though. Strapped to the fake soldier’s flak jacket was a sand-coloured case, roughly the size of a lunchbox but much thinner. Once I saw the attached stylus, I knew that it was for a smartphone or tablet.

This particular case held a white Samsung Galaxy Note 3, a device that DARPA researchers would later tell me is one of their favourites. The case enables soldiers to keep both hands free, while looking down at the screen, and also plug into an auxiliary battery pack on their backs that can keep the device running for a solid week. It was all custom-built, all except for the chunk of plastic with the Samsung logo on it.

“The end user device is the most important part,” Doran told me. He went on to explain how the government’s attempts to build its own smartphone simply didn’t work. And the way that he explained the situation, it seemed kind of silly that they’d even try, since all the devices that were already on the consumer market worked well enough for millions of people to use them on a daily basis. Furthermore, soldiers were already familiar with the consumer devices. The TransApp team just figures out which of the existing devices fit the specific needs of a particular mission, and how, if at all, they’d need to modify the device.

“For the hardware, we constantly have a roster,” Doran continued. “We’ve got stuff on deck, ready to jump when we need to. We’ll put stuff in ovens; we’ll put it under a spotlight to see how good the screen brightness is.” And so on. Based on how he described them, these are not typical tests that the phones would see in the Samsung R&D department. Doran added, “We have to be very dynamic, and we don’t necessarily plan to give everyone all the same thing. But everything needs to work together.” To do so, everything runs on a highly modified version of the Android operating system.

The more we talked about networking technology, the more things started flying over my head. I’d heard of Wave Relay radios before, for example, but I had a hard time following how the Army used them to set up a secure, mobile network throughout the city of Kandahar. By the time Doran showed off a radio system that’s designed to fly around on a drone and pinpoint the location of terrorists based on cell phone signals, it was clear that we were venturing into a level of detail that wasn’t exactly cleared for public knowledge. Once the word classified started getting thrown around, I came to the stark realisation that — as impressive as it was — all of this technology wasn’t just developed to protect our soldiers in combat. Some of it was developed to help us kill better.

What It Takes to Win Wars

TransApps isn’t about making iPhones that shoot holograms (unfortunately). It’s about creating a whole new process of innovation not only for the Pentagon but also for the entire tactical community, including law enforcement and rescue operations. These are men and women with extremely difficult jobs that require a fundamentally different set of tools. In the past, developing new ways of communicating and new ways of doing things required multiple levels of oversight, in part, because security is such a big concern.

Looking forward, however, folks like Doran are trying to adapt the model that consumer technology uses to create such amazing products to work in a tactical environment. If a soldier or a police officer has an idea for an app that would make his job easier, he should also have a way to build it. And so as the TransApps nears the end of its funding, it’s focusing on creating that workflow so that development of these types of apps can continue in different tactical communities, from the military to law enforcement.

Everything made more sense once I started meeting members of the team. We walked from the awkwardly empty conference room past the coffee machine and past a small bomb-diffusing robot to the bullpen.

There, in the shadow of giant green Android robots painted on the wall, a couple dozen twenty-somethings were busy hammering away at code. In one corner, a tall kid wearing an Oculus Rift headset careened this way and that like an old man who’d lost his glasses. (He was developing virtual reality training modules for tank drivers.) In another, a young girl wearing what appeared to be a modified version of Google Glass stared at her laptop, slack jawed. (They wouldn’t tell me what she was developing.) It was a scene I never imagined I’d see in the Department of Defence.

“This office actually feels more like an incubator,” I said smiling.

“That’s what we want,” said one of the researchers, smiling.

“Yeah, we’re not going to do the wood panel computer farm that the DoD probably came from,” Doran chimed in. “But we’re just always exploring how to better evolve and adapt. We don’t want to change for the sake of change, we just want to keep getting better.”

Doran went on to explain how disrupting the Pentagon’s workflow was a necessary but tedious task. While it’s ok for someone like Mark Zuckerberg to encourage his employees to break stuff, lives are at stake in some of the scenarios that TransApp confronts. Smartphones are fun and helpful for civilians going to the office and to the park and what not, but for soldiers to add the extra weight and distraction, they have to make it count. Every ounce of gear they carry counts.

That gives the developers a difficult directive. “Most of what these people are working on are combat systems,” Doran explained. “They have likely never been shot at, but our high level programmers need to develop apps for the users who are.”

Doran went on to explain how TransApp developers work directly with soldiers who’ve seen combat to improve the apps they build. The developers also go through a “Hunger Games-themed workshop,” in which they test the app in more stressful environments. It’s not exactly combat, but it’s definitely more intense than hammering out code.

The thing is, the military could use more code on the battlefield. While DARPA researchers have done a good job laying the groundwork for a new app ecosystem, the TransApp program runs out of funding this year, and for the most part, the Army will take over the larger effort that DARPA started to get smartphones in soldiers’ hands. That means it will be up to the troops to develop and maintain these apps. When DARPA’s contracts expire, there’s a chance the Army contract the same developers to continue the work, but there’s no guarantee. Based on how Doran described the future of smartphones in the military, though, it sounded unlikely that the effort would completely be abandoned.

When Apps Save Lives

After we’d done a lap around the office, I finally got to sit down and take a battlefield-ready smartphone for a test drive. The experience was actually a lot more familiar than I expected, and that’s kind of the point. The Samsung device was Doran pointed me towards the maps app, which he described as the most important of them all. It looks a little bit like Google Maps, but it does a lot more. Basically, the map serves as a platform on which the phone can run any number of plugins, everything from drawing up mission plans to tracking drones. A related app called TransHeat records where the soldiers go so that future missions will know which routes are well-traveled and which are uncharted and potentially dangerous. Another, called PLI, is used to avoid casualties from friendly fire, known in military-speak as “blue force tracking.”

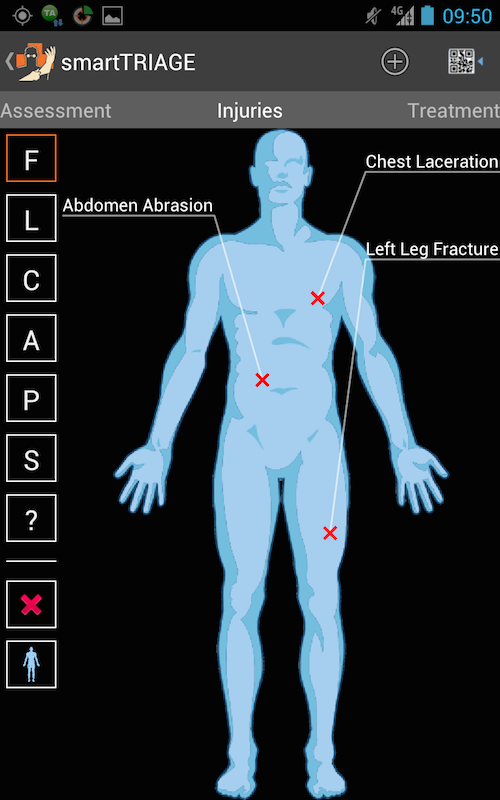

The list goes on and on. There’s a ballistics calculator app for snipers, as well as a general guide to weapons and ammunition called WAM. Debrief makes it easy to compile mission reports on the fly. Trip Ticket keeps track of personnel and inventory. GammaPix is for measuring radiation levels. SmartTRIAGE helps medical teams identify and catalogue injuries or health problems on the battlefield. It’s as simple as tapping on a human figure, selecting the diagnosis, and recommending a treatment plan. And what’s especially important — and impressive — is that the vast majority of the apps work off the grid.

One app that caught my eye is called WhoDat. Doran described it as “a soldier-driven picture book,” but I like to think of it as Facebook for war. It lets soldiers study up on who’s who both before they’re deployed and while they’re on the battlefield. “You can flip the pictures over, put notes on them, share content as a way for them to keep track,” Doran explained. “And you can separate them into groups: good guys, bad guys, friends, targets for reconciliation, the UN team.” It wasn’t immediately clear to me if all of the units took their own pictures of locals and added them to a central database, but that makes the most sense based on how Doran described the app.

It sounds so stupid simple, because it is. Just imagine how useful it would be for soldiers to have a basic directory at their fingertips, while they’re trying to keep track of who they’re fighting against and who’s on their side. This kind of information can amount to life or death for some soldiers.

As we wrapped things up at the TransApp headquarters, I realised that Doran hadn’t eaten the lunch he’d been carrying earlier. It didn’t seem to phase him one bit. I’ve never met a government employee who was so visibly and viscerally excited about what he was doing. I stuck around a little longer to hear Doran tell stories of the time he spent in Afghanistan gathering feedback from soldiers who were using TransApp technology in the field. Just imagine these guys, many of them in their early 20s, who’ve spent the past five years with a smartphone in their pocket and suddenly have to go to war with a what Doran described as World War II-era radios. Just imagine how exciting it would be for the Army to give them a Samsung Galaxy instead.

Despite Doran’s efforts and the progress TransApp has made, our troops will still be carrying those heavy radios for the foreseeable future. The military will inevitably phase in smartphones as security and budgets allow. However, it’s encouraging to see how the military’s evolving in how it develops new technology. It’s exciting to realise that there’s a futuristic laboratory of ideas and innovation in Washington, a place where developers do break things sometimes so that they might save a soldier’s life.

I left DARPA’s offices in a bit of a haze. It might’ve been the midsummer heat, or it might’ve been the four hours I’d just spent talking about war. Either way, I was turned around and didn’t know how to find my way home. So, like I do every day, I reached into my pocket and felt the cool comfort of my own smartphone with my Google Maps and my text messages and my stupid puzzle game. I never felt so spoiled.

Pictures: DARPA / Gizmodo