Sometimes it’s easy to forget that Steve Jobs was once quite a visionary. His legacy has arguably been tarnished by stories of his need for total control, the bizarre antics at the end of his life, not to mention a shitty biopic starring Ashton Kutcher which hopefully won’t be the last word on the man. But when you look back at the early days of Apple, you’re reminded of his tremendous ability to peer into the future.

Longform has republished an interview that Jobs did with Playboy back in 1985. It’s a great reminder that Jobs truly was an extraordinary thinker. Perhaps most impressively, he placed his company within the context of communications history before helping thrust us into tomorrow.

In the interview, Jobs insists that one day, “computers will be essential in most homes.” Why’s that exactly? Jobs foresaw a nationwide communications network that would allow people to tap into an incredible wealth of information.

Use of the burgeoning internet in 1985 was still limited largely to university researchers and military personnel. But notice that he says nationwide, rather than worldwide. Perhaps because worldwide would have sounded too sci-fi, even as a worldwide network was emerging behind the scenes.

Playboy: What will change?

Jobs: The most compelling reason for most people to buy a computer for the home will be to link it into a nationwide communications network. We’re just in the beginning stages of what will be a truly remarkable breakthrough for most people — as remarkable as the telephone.

Playboy: Specifically, what kind of breakthrough are you talking about?

Jobs: I can only begin to speculate. We see that a lot in our industry: You don’t know exactly what’s going to result, but you know it’s something very big and very good.

Playboy: Then for now, aren’t you asking home-computer buyers to invest $US3000 in what is essentially an act of faith?

Jobs: In the future, it won’t be an act of faith. The hard part of what we’re up against now is that people ask you about specifics and you can’t tell them. A hundred years ago, if somebody had asked Alexander Graham Bell, “What are you going to be able to do with a telephone?” he wouldn’t have been able to tell him the ways the telephone would affect the world. He didn’t know that people would use the telephone to call up and find out what movies were playing that night or to order some groceries or call a relative on the other side of the globe. But remember that first the public telegraph was inaugurated, in 1844. It was an amazing breakthrough in communications. You could actually send messages from New York to San Francisco in an afternoon. People talked about putting a telegraph on every desk in America to improve productivity. But it wouldn’t have worked. It required that people learn this whole sequence of strange incantations, Morse code, dots and dashes, to use the telegraph. It took about 40 hours to learn. The majority of people would never learn how to use it. So, fortunately, in the 1870s, Bell filed the patents for the telephone. It performed basically the same function as the telegraph, but people already knew how to use it. Also, the neatest thing about it was that besides allowing you to communicate with just words, it allowed you to sing.

Playboy: Meaning what?

Jobs: It allowed you to intone your words with meaning beyond the simple linguistics. And we’re in the same situation today. Some people are saying that we ought to put an IBM PC on every desk in America to improve productivity. It won’t work. The special incantations you have to learn this time are “slash q-zs” and things like that. The manual for WordStar, the most popular word-processing program, is 400 pages thick. To write a novel, you have to read a novel — one that reads like a mystery to most people. They’re not going to learn slash q-z any more than they’re going to learn Morse code. That is what Macintosh is all about. It’s the first “telephone” of our industry. And, besides that, the neatest thing about it, to me, is that the Macintosh lets you sing the way the telephone did. You don’t simply communicate words, you have special print styles and the ability to draw and add pictures to express yourself.

You can read the entire interview over at Longform. The whole thing is really worth a read. Hat-tip to Chris Dixon.

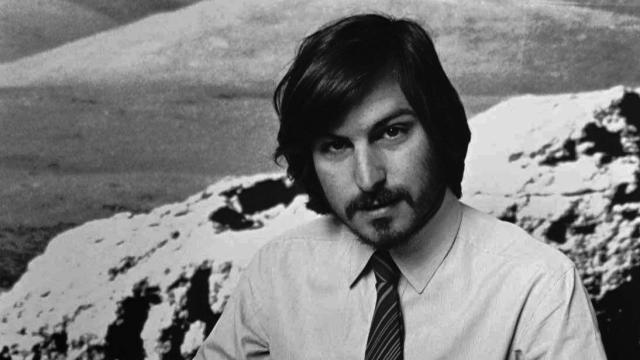

Image: Steve Jobs in 1977 via AP