Here are some sordid scenarios. Your ex-girlfriend can see every time you swipe right while using Tinder. Your former husband is secretly listening to and recording your late-night Skype sessions with your new boyfriend. Some random slippery-dick is jacking off to the naked photos in your private photo library. For millions of people, it’s not hypothetical.

Someone could be spying on every call, Facebook message, snapchat, text, sext, each single keystroke you tap out on your phone, and you’d never know. I’m not talking about the NSA (though that too); I’m talking about software fine-tuned for comprehensive stalking — “spyware” — that is readily available to any insecure spouse, overzealous boss, overbearing parent, crazy stalker or garden-variety creep with a credit card. It’s an unambiguously malevolent private eye panopticon cocktail of high-grade voyeurism, sold legally. And if it’s already on your phone, there’s no way you can tell.

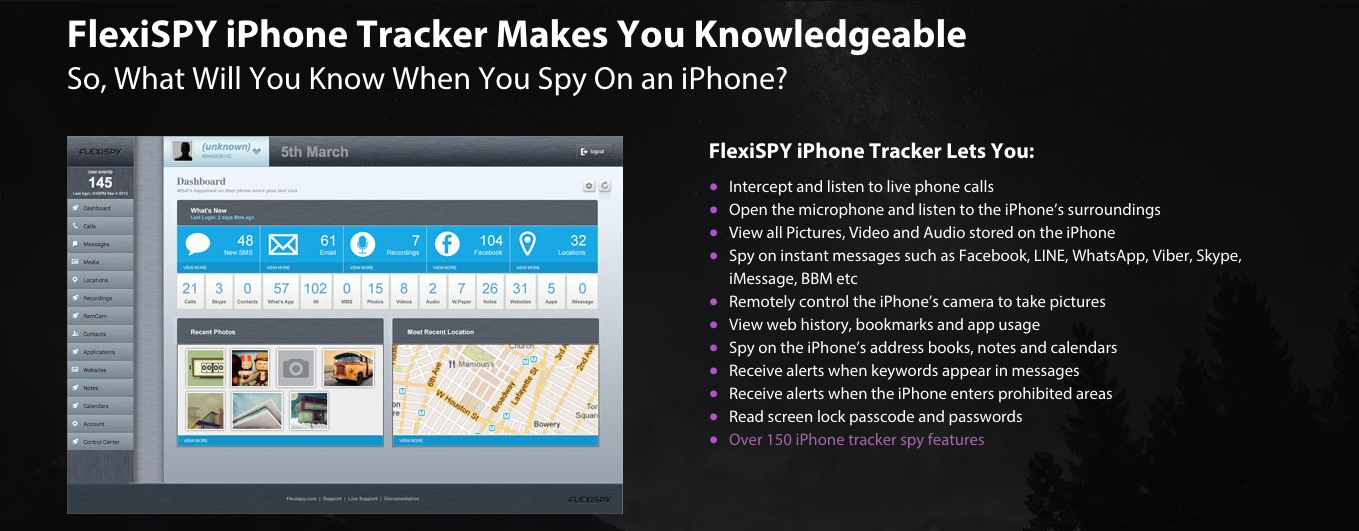

Spyware companies like mSpy and flexiSPY are making money off the secret surveillance of millions of people’s devices. Literally millions of people, according to the sales figures provided by these spyware companies, are going about their days not knowing that somewhere, some turdknockers are scouring their photo libraries and contacts and WhatsApp messages, looking for digital misdeeds.

Spyware has been around for decades, but the current crop is especially invasive. They make money by charging people — from $US40 a month for a basic phone spying package on mSpy up to $US200 a month on one of flexiSPY’s bigger plan — for siphoning activity off their target’s devices.

If someone is alone with a device for a few minutes, or if they have the iCloud credentials of their targets, they can upload sophisticated tracking software that will let them follow along with whatever’s happening on their target’s device. To keep peeping, they keep paying.

In some cases, these spywares require their users to have access to jailbroken phones. Other times, you can install remotely. But the degree of difficulty is not so high that it will dissuade the suspicious from opening their window to someone else’s private life. These disconcerting peepshows happens because spyware companies keep selling easy ways to make them happen. These softwares facilitate, at the very best, ghastly invasions of privacy from parents and, at the worst, violent stalking. They should be banned. They’re not.

Legal disclaimers tucked into the small print of their websites decry using this spyware for “illegal purpose,” and serve as flimsy legal shields that could easily be penetrated, if only law enforcement took the time to prioritise shutting these stalking-aid manufacturers. These disclaimers clash with often blatant advertising recommending spying on romantic partners. flexiSPY boasts about its ability to catch wayward spouses right on its homepage. Stalking cheaters is a cornerstone of its ad campaigns. And mSpy insists that it’s made primarily for parents who want to monitor their children and employers who want to keep tabs on their employees, but the use case.

mSpy founder Uri Soroka is a father who will argue the app is a way to protect children, but even a cursory look at the company’s promotional materials makes it clear the software targets suspicious intimates just as much, if not more, than anything else. Plus, stats don’t lie: mSpy counts 40 per cent of its users as parents, and 10-15 per cent as employers. It doesn’t account for the 45-50 per cent who use it for ‘other reasons.’ Considering the way it’s discussed as a potent tool to track cheating spouses, the likelihood that many people are using mSpy to play illegal love detective is high.

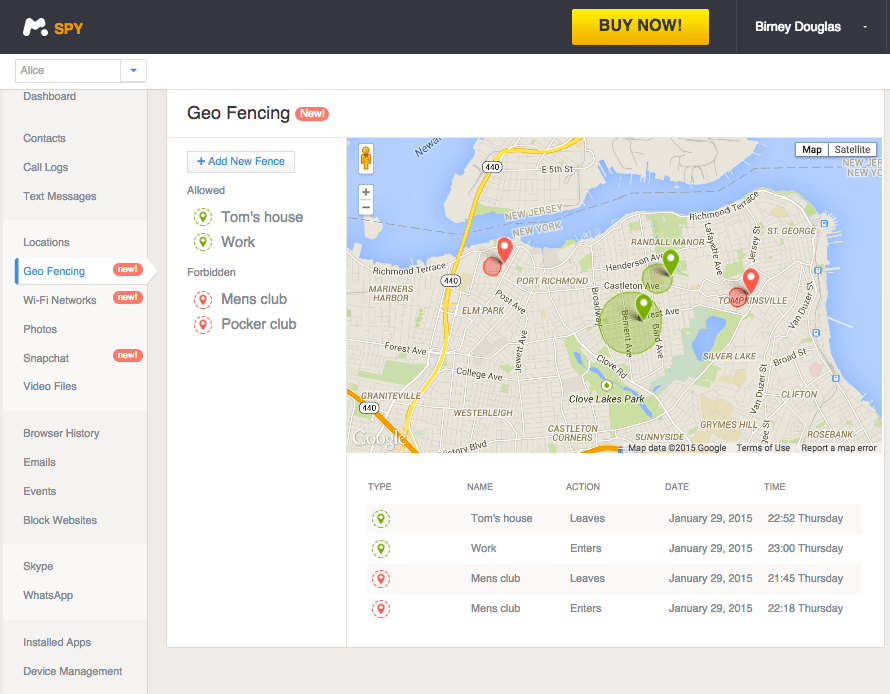

People could also use the software for identity theft. Or simply to be a lascivious, nude-hunting creeps. Since mSpy and flexiSPY both offer geo-location, they’re also potent stalking tools. Both companies offer easy-to-use dashboards that give their clients up-to-date overviews of their target’s phone activity. It’s a voyeur’s dream: An intimate, all-access look into someone’s phone or laptop. And again, nobody’s stopping these companies from selling their spykits to whoever the hell wants them.

In one mSpy testimonial, a man in the collared shirt looks too happy for talking about heartbreak. He starts his pitch with a shrill shill’s staccato, an urgent salesman- “Hey everyone!” He is trilling. “I want to talk to you today about the ultimate cell phone spy!” he looks into the camera, spiel prepped.

“The reason why I got it, a while back I was dating this girl and I thought I was in love with her. And out of the blue, one week, she started acting strange. She was always texting and I’d ask her who it was and she’d say it was her friends or her sister or her family or whatever. But she was being really secretive about it, acting really weird.” The man, still oddly energised by his tender heart’s demolition, went to mSpy’s website. He’s the third person in the YouTube ad to discuss how mSpy solved their problem of not being able to aggressively spy on their lover.

That is a typical mSpy promotion on YouTube, and other spyware services mimic the same formula: regular men and women extolling the virtues of software that lets them completely and utterly violate their partner’s trust in order to see if their partner was completely and totally violating theirs.

Even though their advertising is focused on digitally confirming infidelity, apps like these have two “legitimate” uses that protect them from outright bans. The first is allowing parents to spy on aka keep tabs on children without their knowledge. It’s the most viable legal use, since parents can give consent for their kids, which helps the spyware evade breaking wiretapping laws.

It’s morally questionable, no doubt, but unlikely that a parent sleuthing use case would end up in court (though, of course, if a teenager turns 18 and his parents are still spying on his phone, that’s a stickier legal thicket).

The other “legitimate” use is for employers who put the spyware on their employee’s company phones, since it can be argued that because the employer owns the phone, they are legally allowed to install a monitoring system. This is debatable if the employer doesn’t tell their employees what they have access to. Most employees expect, at this point, that their company emails are fair game. But how many people assume their boss has geo-fencing turned on to see when they go to a bar on a work night, or take a drive on a day they have called in sick?

Unfortunately, these “legit” use cases keep spyware companies in business and their more nefarious uses thriving. Law professor and expert on digital privacy Neil Richards told me it may be hard to outlaw mSpy and its ilk altogether, since its makers can argue it has legal uses, just as tools that burglars use are also tools that licensed locksmiths use.

But “legitimate” uses notwithstanding, these spywares could, and should, be treated as lawbreakers, at the very least for their spouse-spying tools. “When you bill it as 100% undetectable, you are building a criminal model,” privacy researcher and law professor Danielle Keats Citron told me when I called to ask her about the preponderance of spyware still on the market.

Citron’s upcoming law review paper “Spyware Incorporated” marvels at how these invasive apps are still sludging through the market despite, you know, being used for blatantly illegal stuff. She mentions mSpy and flexiSPY in this paper as examples of spyware that hasn’t been banned, and has serious concerns about the genre of software in general, especially about how these softwares create very real danger. Her paper points out several cases where spyware software helped abusive partners stalk people trying to escape them:

A woman fled her abuser who was living in Kansas. Because her abuser had installed a cyber stalking app on her phone, her abuser knew that she had moved to Elgin, Illinois. He tracked her to a shelter and then a friend’s home where he assaulted her and tried to strangle her. In another case, a woman tried to escape her abusive husband, but because he had installed a stalking app on her phone, he was able to track down her and her children. The man murdered his two children. In 2013, a California man, using a spyware app, tracked a woman to her friend’s house and assaulted her.

I’m just going to point out the obvious and say: This is so f**ked up. Citron knows it, and emphasised to me that even the more ostensibly legitimate use cases for spyware, like employee monitoring, are at odds with the Wiretap Act:

“The Wiretap Act forbids the surreptitious interception of communication. So both for individuals, spies… they’re engaging with a model designed to aid and abet secret spying. Federal law also covers the manufacture and advertising of devices primarily designed for surreptitious interception of communications. Which is what they’re doing,” Citron told me. “Sure, they could say ‘oh, legitimate uses,’ but there really are no legitimate uses for undetectable secret surveillance of communication. There just isn’t.”

“When individuals intercept someone’s communication without at least one party’s consent- meaning at least one party from the communication’s consent — that it’s illegal,” Citron went on. I asked her if people could skirt the issue of consent by purchasing and giving a phone as a gift, or as a work product. She told me that even if the employer pre-loads the phone before giving it to an underling, it’s still designed to be surreptitious interception of communication and therefore illegal.

Neil Richards also believes these technologies need to be curtailed. Richards stressed that it would be wise to consider outlawing this sort of spyware altogether, or at the very least licensing it the way the way we licence locksmiths and their skeleton keys. “The point is, however we choose to do it, we should choose to intervene in cases of secret monitoring like this,” he said. “The potential for harm and misery and deceit is obvious. The potential for abuse is obvious.”

In August, the FTC fined StealthGenie, a spyware similar to mSpy and flexiSPY, for violating Section 2512 of the Wiretap Act. CEO Hammad Akbar paid $US500,000 and pleaded guilty.

“The defendant advertised and sold a spyware app that could be secretly installed on smart phones without the knowledge of the phones owner,” U.S. Attorney Boente said in November. “This spyware app allowed individuals to intercept phone calls, electronic mail, text messages, voice-mails and photographs of others. The product allowed for the wholesale invasion of privacy by other individuals, and this office in coordination with our law enforcement partners will prosecute not just users of apps like this, but the makers and marketers of such tools as well.”

The Assistant Attorney General characterised selling spyware as a federal crime after the Akbar case. Yet, as Citron told me, the StealthGenie case is a rarity. Spyware purveyors like mSPy and flexiSPY are continuing their flourishing business unabated, and arrests and shut-downs remain rare.

“We have these laws on the books. Remember, spyware has been around since at least 1995. We’ve only had three prosecutions — one recently in August, with StealthGenie — so there’s a woeful under-enforcement of law, especially at state level. I couldn’t find a reported case on the state level,” Citron said.

“We have this burgeoning market because there seems to be very low risk of criminal enforcement,” she continued. This is often because police lack the forensic tools they need to figure out if spyware is on a device…which makes it hard to prosecute without evidence that anything slimy is even happening.

Citron pointed out that nobody’s afraid of breaking laws that are never enforced. Why would spyware makers stop a lucrative business, when they aren’t getting pursued by law enforcement? They wouldn’t, and they aren’t.

It looks like mSpy is making adjustments, gearing up for a fight. On its Android app, it now only allows people to install the software in its totally undetectable format if they self-identify as employers or parents. This is, of course, extremely easy to circumvent; someone could just say they were an employer and install the secret surveillance tool on their partner’s phone, or even a passing acquaintance.

And there are legislators pushing the issue. Senator Al Franken is pressing for a Location Privacy Protection Act that would expand Section 2512. That’s good news, as is the FTC’s decision to go after StealthGenie. But every day mSpy, flexiSPY, and other spyware continue to sell, they help people to stalk and spy on each other illegally. They are destructive, menacing, and intrinsically at odds with reasonable expectations of privacy. They should have never been allowed to operate and each day they continue is a failure of our government, a failure that endangers its citizens. It’s an embarrassing lapse in protection to provide safe harbours for spyware.

Perhaps the lax attitude law enforcement has towards stalking apps is a symptom of the government’s overarching approach towards digital privacy. Since actual spies feel entitled to blanket surveillance, this dismissive stance towards invading our online lives may be percolating into decisions to enforce laws targeting other surveillance. Just as the government justifies mass surveillance as a means to ensure national security, companies like mSpy are using ostensibly justifiable and legal actions (installing spyware on childrens’ phones) as a catch-all to legitimise spying on other adults without their consent.

Whatever the reason for allowing these spywares to sell their legally dubious and morally reprehensible stalking aids, if you want to protect yourself from sneaky installs, the only thing you can really do is keep your phone locked and never leave it with anyone else. This is a recipe for paranoia, and one we shouldn’t have to develop to keep ourselves safe. Spyware should be banned. People who use this shit illegally should be prosecuted. People who sell this shit knowing that it’s going to be abused should be banned from selling it.

Picture: Michael Hession