At some point in your life you’ve probably encountered a problem in the built world where the fix was obvious to you. Maybe a door that opened the wrong way, or poorly painted marker on the road. Mostly, when we see these things, we grumble on the inside, and then do nothing.

But not Richard Ankrom.

Courtesy of Richard Ankrom.

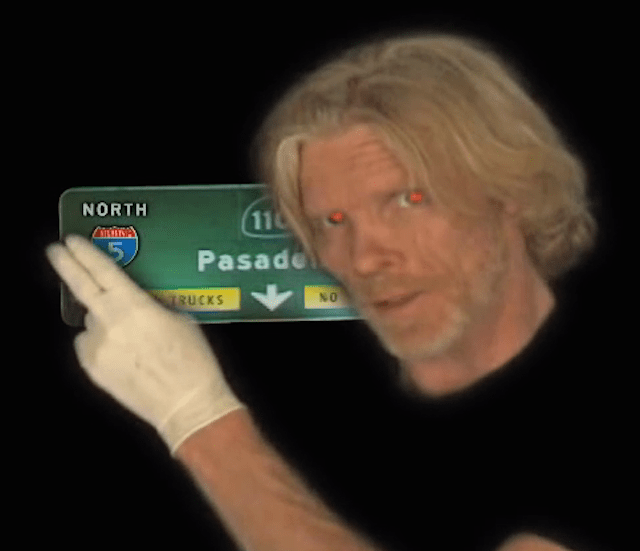

In the early morning of August 5, 2001, artist Richard Ankrom and a group of friends assembled on the 4th Street bridge over the 110 freeway in Los Angeles. They had gathered to commit a crime — one Ankrom had plotted for years.

Courtesy of Richard Ankrom.

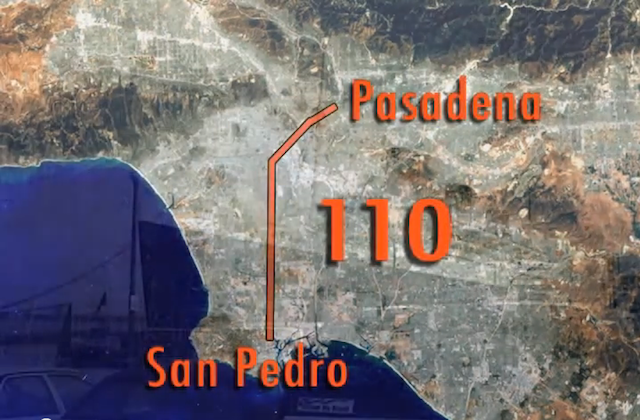

Twenty years earlier, Ankron, then living in Orange County, was driving north on the 110 freeway. As he passed through downtown Los Angeles, he was going to merge onto another freeway, the I-5 North. But he missed the exit and got lost. And for some reason, this stuck with him.

Years later, when Ankrom moved to downtown Los Angeles, he was driving on the same stretch of freeway where he’d gotten lost before. He looked up at the big green rectangular sign suspended above and realised why he missed the exit all those years ago.

The sign was not adequately marked.

Image courtesy of Richard Ankrom.

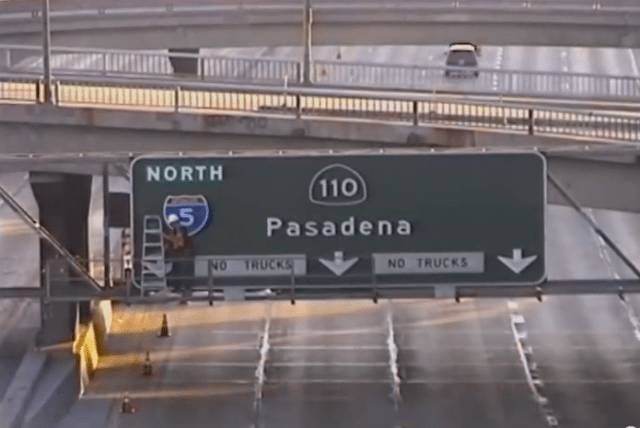

The I-5 exit wasn’t indicated on the green overhead sign. It was clear to Ankrom that, the California Department of Transportation (known as Caltrans) had made a mistake.

Ankrom, an artist and sign painter, decided to make the Interstate 5 North shield himself. He also decided that he would take it upon himself to install it above the 110 freeway.

He would call it an act of “guerrilla public service.”

Courtesy of Richard Ankrom.

Ankrom started by studying L.A. Freeways signs and holding up pantone swatches to perfectly match the paint colour. He dangled over bridges to measure the exact dimensions of other signs.

Image courtesy of Richard Ankrom.

Most importantly, Ankrom consulted the MUTCD, The Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices, which provides “uniform standards and specifications for all official traffic control devices in California.”

Courtesy of Richard Ankrom.

Ankrom wanted his sign to be built to the exact specifications of Caltrans, which were designed to be read by motorists travelling at high speeds. He copied the height and thickness of existing interstate shields, copied their exact typeface, and even sprayed his sign with a thin glaze of overspray of grey house paint so that it wouldn’t look too new.

If he was successful, no one would know that the signs weren’t put up by Caltrans.

Courtesy of Richard Ankrom.

As a finishing touch, Ankrom signed his name on the back with a black marker, like a painter signing a canvas.

Then came the next phase of the project: the installation. Ankrom planned it with the precision of a bank heist. He cut his hair, bought some work clothes and a hardhat and an orange vest. He even made a Caltrans contractor-esque decal for his pick-up truck.

He feared he could get arrested, or worse — drop the sign or one of his tools on the cars driving underneath. But he felt it was too late to turn back.

Courtesy of Richard Ankrom.

On August 5, 20o1, Ankrom parked his truck and went to work. He positioned his ladder over the razor wire and made his way up to the catwalk under the sign, nearly 30 feet above the highway.

Image courtesy of Richard Ankrom.

The whole installation took less than 30 minutes. As soon as the sign was up, Ankrom packed up his ladder, rushed back to his truck, and blended back into the city.

For about nine months, only a small group of people knew that the Interstate 5 shield hanging above the 110 freeway was a forgery. Then one of Ankrom’s friend leaked the story to a local paper. And that’s how Caltrans found out.

Courtesy of Richard Ankrom.

Ankrom had hoped he could get his sign back from Caltrans after they took it down; he figured he would hang it in an art gallery. But Caltrans didn’t take the sign down. His guerrilla sign had passed the Caltrans inspection.

Image courtesy of Richard Ankrom.

More than eight years after after Ankrom’s sign went up, he got call from a friend who noticed some workers taking it down. It had been replaced with as part of routine maintenance.

When the new sign went up, Caltrans had added the I-5 North shield not only to it, but also to two additional signs up the road.

Courtesy of Richard Ankrom.

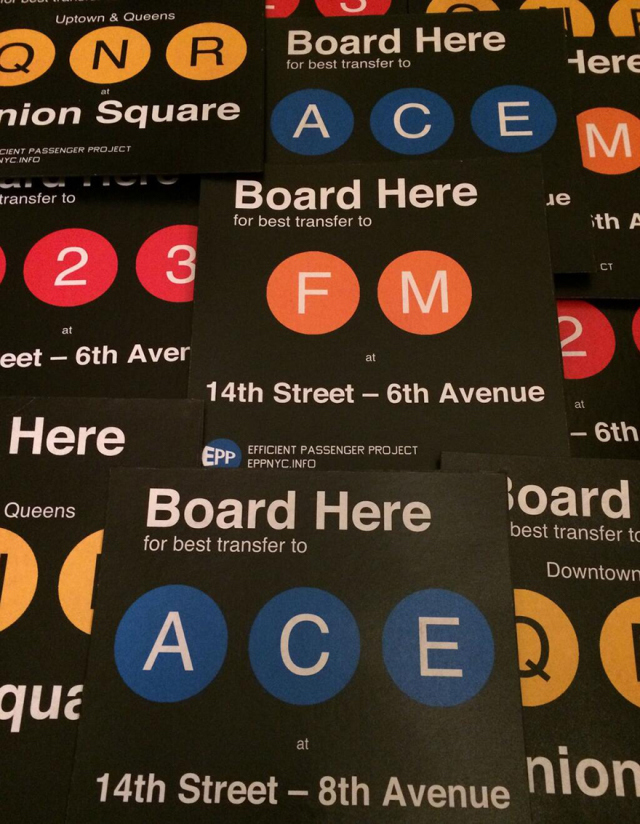

There is another guerrilla public service project in New York City by group called the Efficient Passenger Project. The EPP has been hanging signs in subway stations informing people where they should board the train to make the most efficient transfers.

Courtesy of EPP NYC.

Even though the EPP’s signage has the look and feel of those from the MTA, they are completely unaffiliated. The MTA considers these signs vandalism, and is taking down the signs as fast as they go up.

Point being, if you decide to undertake an act of “Guerilla public service,” just know that it may not be received as such. Proceed With Caution.

Reporter David Weinberg spoke with artist and guerilla public servant Richard Ankrom, and Ankrom’s friend and co-conspirator Amy Inoyou. David is a reporter with Marketplace and host of the podcast Random Tape.

99% Invisible, the greatest podcast of all time, is a tiny radio show about design, architecture & the 99% invisible activity that shapes our world. You can Like them on Facebook here or follow them on Twitter here. To subscribe to the podcast on iTunes, head over here.

This post has been republished with permission from Roman Mars. It was originally published on 99% Invisible’s blog, which accompanies each podcast.