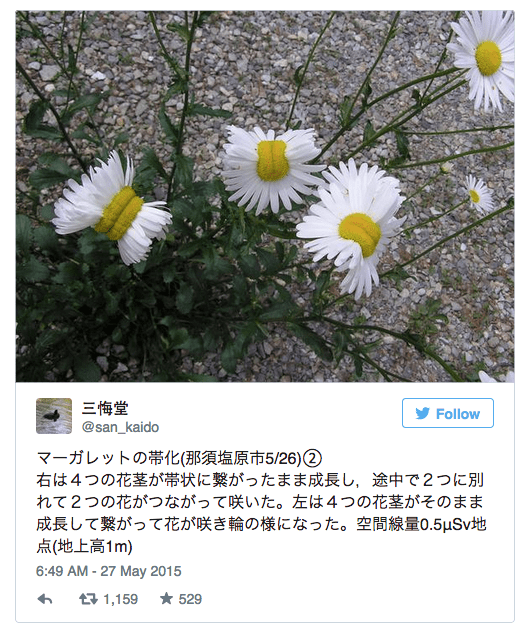

A picture of some deformed plant sex organs is alarming people all over the internet this week. The photo, taken by Twitter user @san_kaido, shows a bunch of daisies that look like conjoined twins. The accompanying tweet describes their twisted, ribbonlike appearance, and reports a radiation reading for the spot.

Given that the photo was taken in Nasushiobara City, about 80 miles from the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster site, the radiation data is probably what made news organisations across America freak out. (We wanted to ask @san_kaido more, but he wasn’t taking any more interviews). But it turns out that particular type of deformity can also be the result of a virus or insect damage, and moreover, the background radiation reported is unlikely to harm a plant.

The Word of the Day Is Fasciation

Plants grow by adding new cells at the tips of their stems from a region called the apical meristem. The meristem contains a reservoir of undifferentiated cells that can start new stems, leaves, or flowers; those cells are usually arranged in a tiny dome. But if a few cells in the meristem die, the dome can get flattened or curved. And that little shape change can have a huge effect on what the plant that grows out of it will look like — the plant parts growing from the distorted meristem have the same flattened and distorted shape. For the flowers in question, they look weird because they’re not growing symmetrically, and we expect our daisies to be symmetrical.

The phenomenon is called fasciation. And although it can be the result of a mutation that affects the meristem’s ability to maintain its shape, it can also be caused by anything that can simply kill off a few meristem cells: bacterial or viral infections, mechanical injury to the plant, even a heavy rain after a long drought. According to University of Massachusetts plant biologist Elsbeth Walker, it’s actually pretty easy to find plants with this condition if you’re looking for them. “If you go into any greenhouse to buy a houseplant you’ll probably find at least one — they’re a dime a dozen.” Even more likely, you’ve eaten one — strawberries sometimes fasciate into enormous fan-shaped berries.

But What About the Radiation?

Granted, mutation can cause fasciation. And that background radiation level — 0.5 μSieverts/hour, according to the tweet — is certainly higher than the background levels found in other parts of Japan. But the question is whether that’s enough radiation to damage or mutate a plant, and by extension, the people near the plant.

Let’s do the maths.

Sieverts (Sv) are units that are used to measure how much damage is caused by radiation absorbed by living tissue. Specifically, 1 Sv represents the effect on 1 kilogram of human tissue after it absorbs 1 joule of energy. One Sv all at once would make you sick, but we’re actually exposed to small amounts of radiation every day — from sources like cosmic rays, radon, coal power plants, and CRT monitors — and we’re perfectly capable of absorbing those low doses safely. For convenience, we typically measure these doses in microSieverts: 1μSievert (μSv) is equal to 0.000001 Sv.

Since plants can’t move, we can assume that the daisies have been growing there all season, exposed to a background radiation of 0.5 μSv each hour. That means that over the course of a day, the plant accumulates: 0.5 μSv/hour * 24 hours/day = 12 μSv/day.

And over the course of a year, it accumulates: 12 μSv/day * 365 days/year = 4380 μSv/year.

Most sources give yearly dose averages in milliSieverts (mSv), so let’s convert our units for ease of comparison: 4380 μSv/year = 4.38 mSv/year.

According to the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission, the average American picks up a radiation dose of 6.2 mSv/year from background sources. Other sources report somewhat higher or lower values, which isn’t surprising because background radiation can vary a lot from place to place. Still, it’s undeniable that the current background exposure that those daisies are getting is lower than what you’re probably accumulating in your normal daily life. And it’s well below the maximum permitted dose for radiation workers in the United States of 50 mSv.

But what if plants are super sensitive to radiation?

Diving into the botany literature, you find that a lot of scientists in the 1950s spent their time zapping plants with X-rays and gamma rays. And it turns out fasciation is a typical plant response to damage caused by ionizing radiation. But it takes a lot of radiation to induce that damage. A 2004 review published in the Journal of Radiological Protection estimates that the smallest radiation dose needed to change normal plant growth is about 100 μSv/hour. That’s three orders of magnitude larger than @san_kaido’s measurement.

To be fair, Shasta daisies are perennials: It’s possible this particular plant was alive during the 2011 earthquake, tsunami, and subsequent meltdown of the Fukushima plant. If so, it would have absorbed a larger dose of radiation around the time of the accident. Could that have been enough to mutate it?

Fortunately for our purposes, radiation readings from June and July of 2011 for Nasushiobara City are available on this handy Google Map. Two months after the accident, background radiation in that city was 740 nanoSv/hour. That’s the same as 0.74 μSv/hour: higher than current background readings, but still orders of magnitude less than it takes to mutate a plant.

Verdict: Weird-Looking Daisies, Highly Unlikely To Be Mutated By Radiation

I can certainly understand where @san_kaido’s concern is coming from. Four years after the Fukushima Daiichi disaster, Tochigi prefecture is still subject to export restrictions on meat, spinach, and other vegetables. And the whole experience must have been scary as shit. But in this case, it’s far more likely that those weird looking daisies got started when the plant fought off a disease or made a copying error as its cells divided.

[White 1948, Real et al. 2004, Bell and Bryan 2008]

Pictures: White Mule’s Ears from Idaho by Perduejn via Wikimedia; Saguaro Cactus by Alan Vernon via Wikimedia; Common Daisy from Germany by Wurzlseppl via Wikimedia