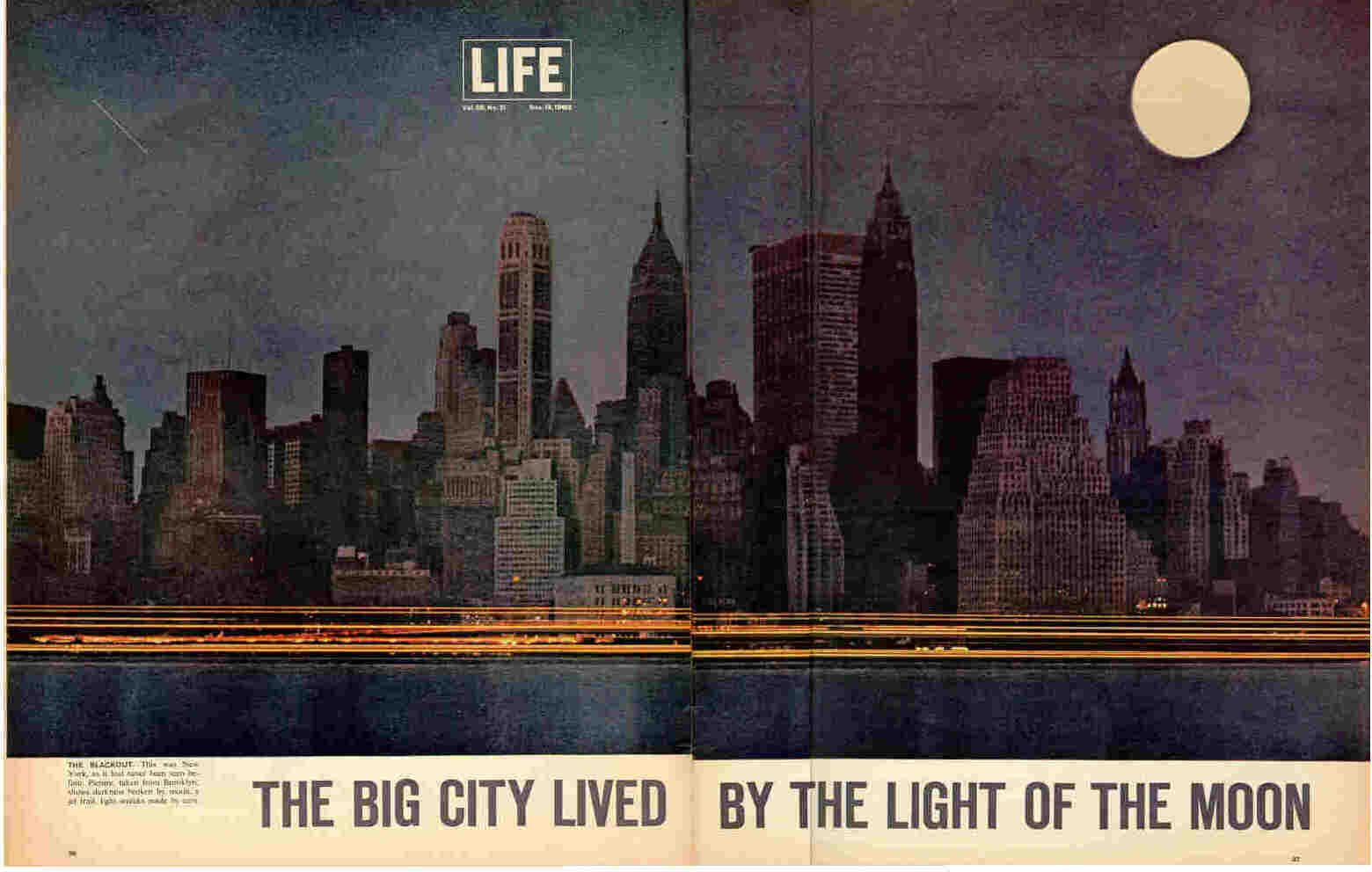

Fifty years ago yesterday evening, at roughly 5:15pm, every light connected to New York’s power grid flickered out — along with those of 30 million people throughout the Northeast. Chaos didn’t ensue, oddly enough.

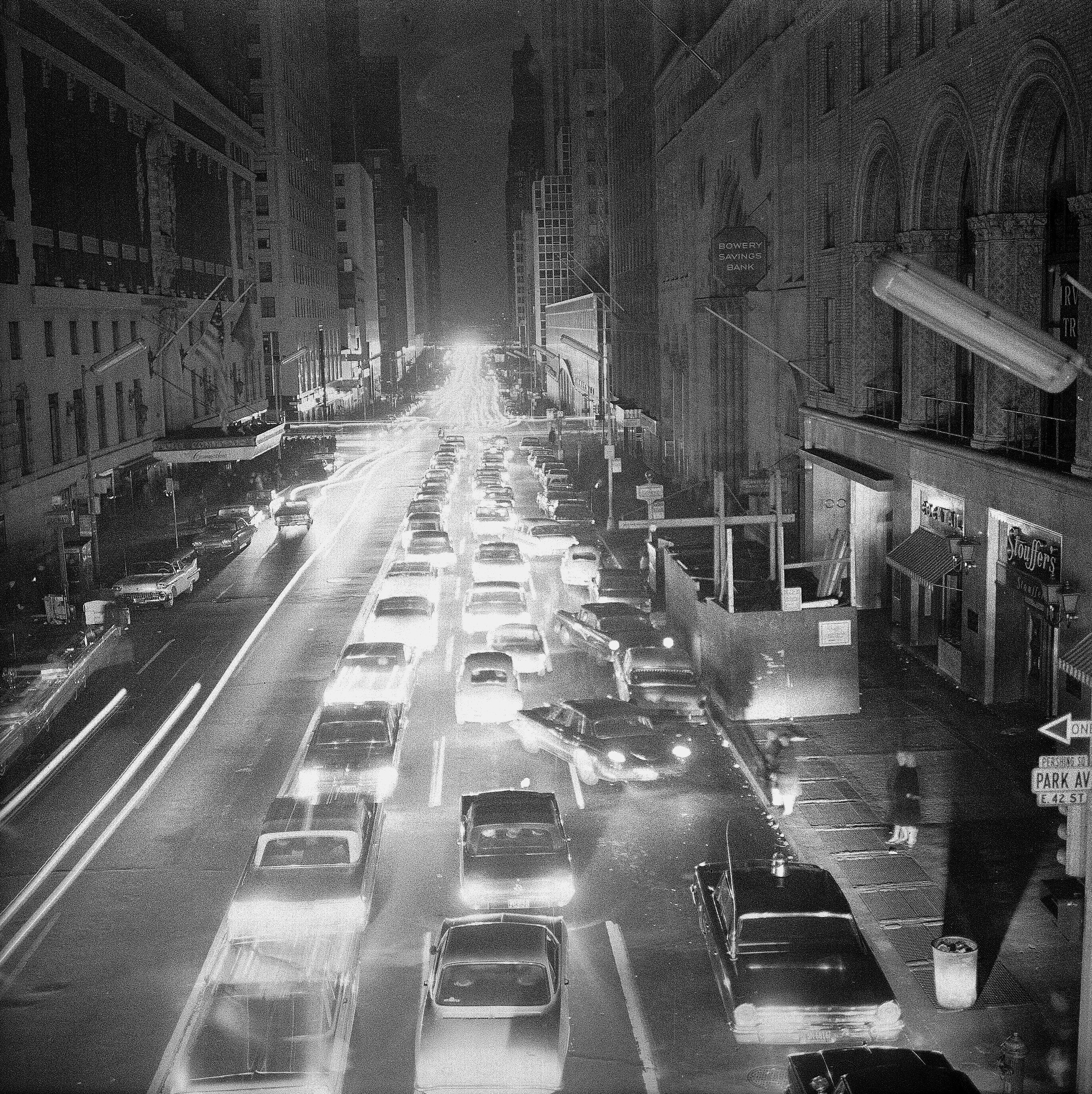

Today, blackouts are scary, for the flashlight prices and cab fares if not the threat of crime. But the great Northeastern Blackout of 1965 was different. While many millions of people were left without power — with as many as 800,000 people trapped in subway cars alone, the New York Times reported — with no explanation of what had caused the outage, there was surprisingly little chaos or panic reported.

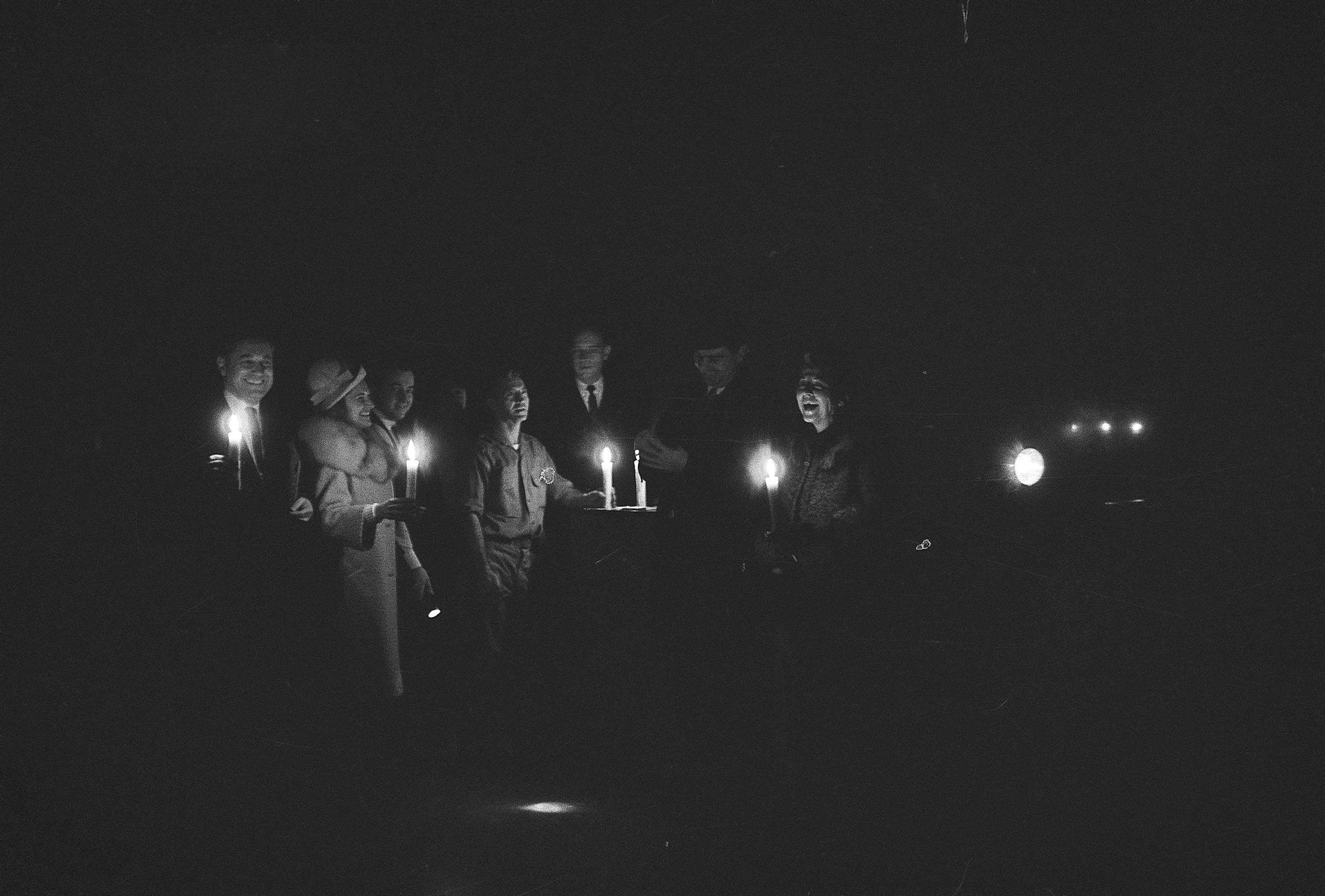

The AP — which made its 50-year-old archival report about the blackout available yesterday — wrote that it was the biggest blackout in history. Yet people seemed oddly calm: “The great luminous cities looked as if they had been struck by some awesome tragedy. But reports indicated most people took it all calmly. Restaurants did a thriving business by candlelight.”

AP.

In Grand Central, people slept on the floors. In the subways, ladders were deployed helped people climb out of the subway tracks. George Mason University’s Blackout Project, which collects accounts from survivors, includes many accounts of the festive and “serene” night. Like this one:

Manhattan was beautiful in the dark. I had to go the upper east side go get my friend. there were [garbage] cans afire along the street, not because of vandalism, but for light. People stood in groups and talked to each other. stores kept doors open and were candlelit. […] calm and serene, not menacing or dangerous.

Or this one:

On the other side of the bridge in Brooklyn, people were out in the streets directing traffic and helping in any way they could. It was incredible how everyone just pitched in; black, white, Hispanic, it didn’t matter. It made you proud to be human.

A “city’s glitter goes,” The New York Times’ front page read the next day, “but not its poise.” While some suspected a Soviet scheme, that idea was discounted after a root cause of the blackout was found at a generating station in Ontario. At worst, the Times recounted, people drank:

A young actress who lives in Greenwich Village was taking a bath when the lights went out. She said that her first thoughts were that ‘we were under attack,’ but that she quickly dismissed such an idea and poured herself a drink.

Passengers “sit patiently in near-darkness” at West 4th Street. AP Photo/Jerry Mosey.

This all-around chill vibe of the 1965 blackout was hugely different from the infamous blackout of 1977 just 12 years later, which would see looting, arson, and crime reported all over the city.

AP.

There’s actually been a fair amount of academic study of blackouts. Besides projects like George Mason University’s Blackout Project, there are plenty of sociologists and writers who have wondered about what our reaction to a large-scale power outage say about us.

In an essay about blackouts published in Public Space and the Ideology of Place in American Culture, the historian David E. Nye says power outages are unique because they represent “unscripted breaks in social time” when all of the rules and systems that define how cities function fall by the wayside. What’s left depends on the economic and social realities of a city:

The 1977 blackout did not unleash a spontaneous, liminal moment of unity but revealed a deeply fractured society. The prosperity of 1965 had evaporated, and many New Yorkers believed the energy crisis was a permanent condition… [T]he Blackout of 1977 appeared to be one more breakdown of civic order, as a divided society faced a grim and impoverished future.

So why was 1965’s blackout so calm? Was it just that nothing like this had ever happened before, and the idea of complete darkness didn’t seem so strange in a city that was still on the upswing of the post-War boom? Were people more naive? Could you even link it to the economic prosperity of New York in the 1960s, versus the blight-ridden city of 1977?

Mass blackouts cut us off from just about every technology that makes our world modern. Maybe that’s why sociologists are so interested in studying how we react to them. They seem to be perceived as either setting back the clock 100 years to a more pastoral time, or setting it forward 100 years to some imaginary apocalyptic future where modern civilisation has collapsed.

Whether a blackout ends up as a party, or a dress rehearsal for the apocalypse, seems to mainly depend on how inhabitants perceive it. The advice of that Greenwich Village actress from the front page of the New York Times in 1965 still rings true today: Relax. And pour yourself a drink.

All images via AP.