Geckos are well-known for their ability to adhere to almost any kind of surface, making them fantastic climbers. In fact, they’re the largest creatures able to manoeuvre along vertical walls, and a new study concludes that this is because of scaling limitations as animal body size increases.

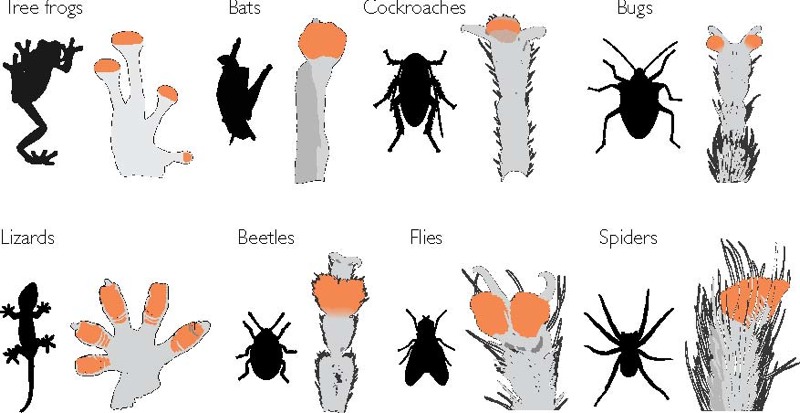

The gecko’s impressive climbing ability is due to billions of tiny hair-like structures on the footpads on the bottoms of their feet, which are small enough that the so-called Van der Waals forces between molecules become significant. That’s also true of other animals with similar abilities, like spiders, cockroaches and beetles, as well as bats, tree frogs and lizards. Although they are quite different creatures in many ways, they all have sticky footpads of varying sizes.

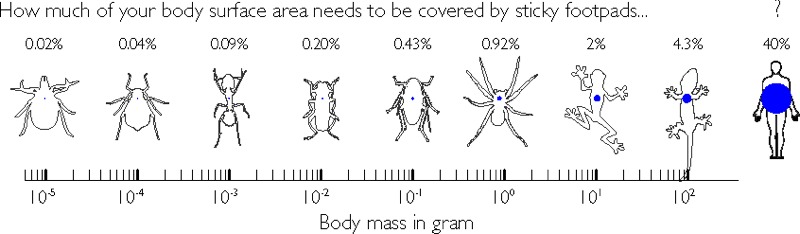

University of Cambridge zoologist David Labonte and several colleagues measured the size of those footpads relative to body surface area in 225 animals, ranging from mites to geckos. And they found that adhesive pads in mites, for instance, require 200 times less body surface area than those for geckos. Following that scaling law, Spiderman would need to cover 40 per cent of his body — fully 80 per cent of his front — in adhesive pads if he wanted to scale a vertical building.

“If a human wanted to climb up a wall the way a gecko does, we’d need impractically large sticky feet — and shoes in European size 145 or US size 114,” co-author Walter Federle said in a press release.

That’s because body surface area per volume decreases as an animal grows in size, according to Labonte. “An ant has a lot of surface area and very little volume, and an elephant is mostly volume with not much surface area,” he explained. Bigger and heavier animals need a lot more stickiness to climb a vertical surface, but there’s just not enough body surface area for the necessary large footpads that would be required. The way the scaling works out, a gecko is pretty much the biggest size possible, given those constraints.

There’s a great deal of interest among scientists in developing biologically-inspired adhesives. Thus far, the prototypes have only proven effective on very small areas, and the Cambridge study helps explain why that’s the case.

But bigger footpads are not the only strategy animals have devised to become better climbers. The researchers found that tree frogs, for instance, evolved to make their footpads stickier rather than bigger. If scientists can tease out the exact mechanism behind how the frogs do that, we would have one more avenue toward super-powerful adhesives in the future.

[Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences]

Images: David Labonte/University of Cambridge.