Scientists from China have made history by taking a cell that’s not a sperm cell and then used it to create a live animal. A similar technique could be used one day to treat infertility in humans.

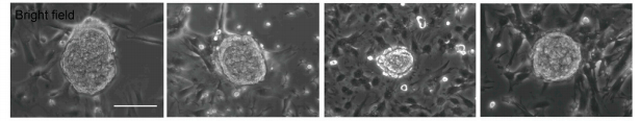

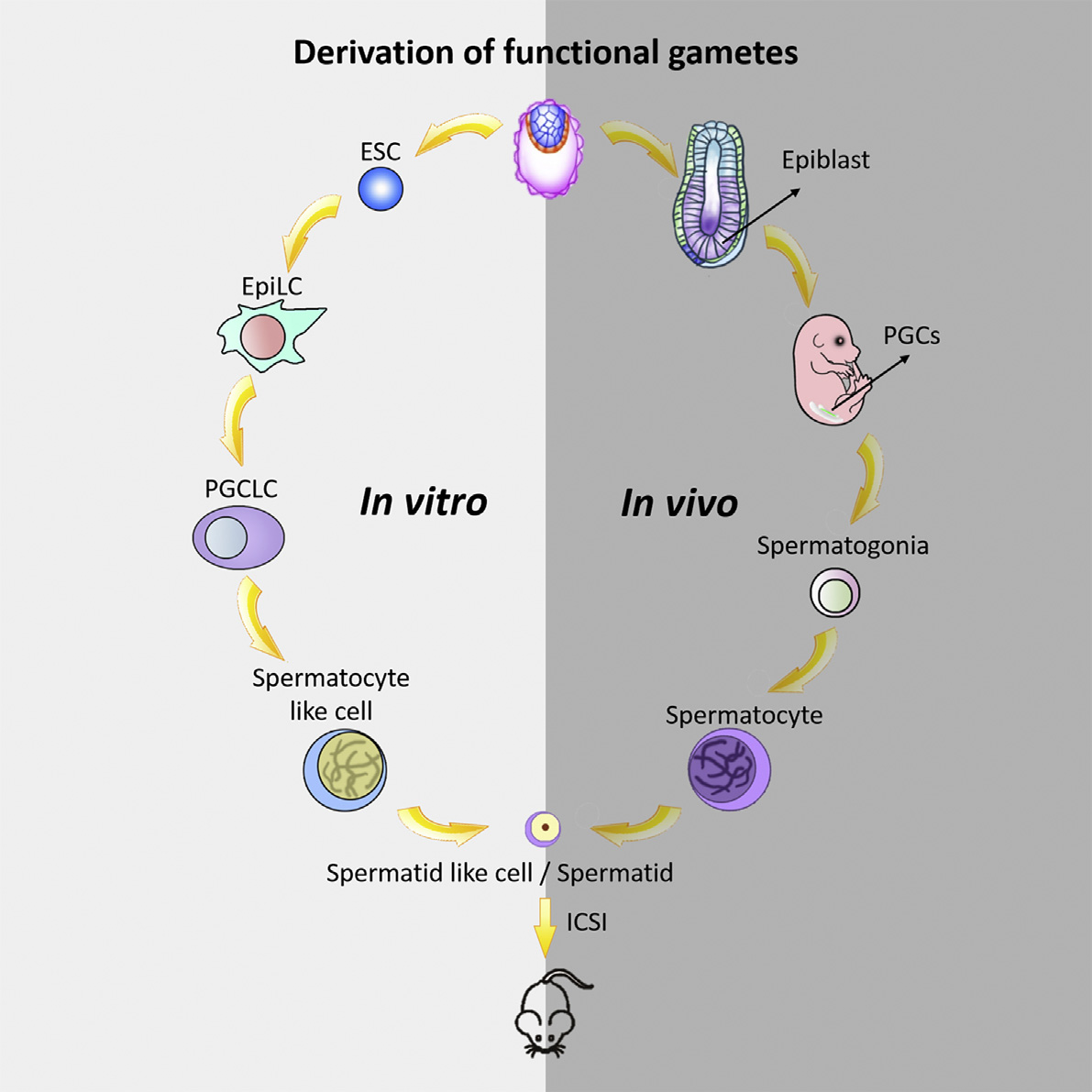

Researchers from Nanjing Medical University created functional primordial germ cells — cells that get passed down to the next generation — from the embryonic stem cells (ESCs) of mice. ESCs are cells that form in the embryo and eventually give rise to sperm. Then they injected the lab-grown sperm into mouse egg cells and implanted the embryos into female mice. The resulting mice appeared healthy and normal, and went on to breed. The details of this groundbreaking work now appear in the latest issue of Cell Stem Cell.

This study must be replicated elsewhere lest we get too carried away with the findings. It’s not known, for example, if the spermatids (as they’re called) had mutations, or if the mice produced by this technique had inherited undetected genetic or chromosomal abnormalities resulting from those mutations. This is a potentially serious limitation. As a potential treatment for human infertility, this makes scientists and ethicists very nervous, as witnessed by the recent controversies surrounding the genetic modifications of human embryos.

“There’s no question that the technique needs to be improved further, but if we can build on this as a technique that is doable in the laboratory, it really is going to change the way we think about cases of infertility that are currently unable to be treated by IVF,” said bioethicist Terry Hassold of Washington State University, who was not involved in the study. “The crucial question is whether someone else is going to be able to replicate the study, and if that is the case then it really will revolutionise assisted reproduction as we know it. All the IVF clinics would be likely to hop on it, although in my opinion that would be very premature.”

Also, the cells used in the study were extracted from embryos (that is, a “third party” genetic donor). So for a man to have genetically related offspring, he’d have to donate his own stem cells to create his own personalised sperm. Theoretically, human stem cells are likely capable of performing the same trick, but scientists still have to prove that.

“Making spermatids in a dish from human embryonic stem cells could have important repercussions,” said University of California, Irvine, biochemist Peter Donovan. “It would allow scientist to continue to understand how our species reproduces, and also offers tantalising possibilities that might one day be used in treating patients with infertility.” If the technique does work for humans, it will be possible to correct genetic defects in the stem cells of infertile patients and use them to make sperm cells capable of fertilising eggs.

Scientists had previously demonstrated that it’s possible to generate germ cells (sexual reproductive cells, like an ovum or sperm) from stem cells. However, they were unable to prove if these cells were functional, or if they were truly capable of meiosis — a type of cell division critical to the formation of functional sperm cells.

The new study, co-led by Jiahao Sha and Qi Zhou, is the first to demonstrate that it’s possible to push embryonic stem cells through meiosis (cell division) to produce a functional gamete, with apparently correct nuclear DNA and chromosomal content, and the ability to produce viable offspring. However, the lab-grown sperm didn’t appear exactly like normal sperm, and they weren’t able to swim.

Moving forward, the researchers would like to study the molecular mechanisms controlling meiosis a bit further. They’d also like to start testing their approach in other animals, including primates. And they will need to show that this technique is applicable to humans, which won’t be easy; the gene expression profile of human germ cells is similar to those of mice, but different in important ways. It could be years before a similar feat is accomplished using human cells.

Top image credit: Southern Illinois University