Once she has lowered herself into the mouth of the cannon and slid down to the base of the barrel, Gemma “The Jet” Kirby performs a series of breath-synchronised movements that seem more suited to yoga or lamaze than to one of the deadliest stunts in circus history. This sequence is the culmination of hours of preparation, the final item on a human cannonball’s pre-flight checklist.

It is essential that Kirby be prepared. The cannon is a notoriously temperamental act, prone to failures human and mechanical alike. Just how temperamental, though, is largely unknown to the general public. Human cannonballing is an exclusive enterprise; of the dozen or so cannonballs performing today, the majority are related by blood or marriage. Their methods are trade secrets, handed down from generation to generation. But Kirby — who, at 25, is currently the feat’s youngest female practitioner — was recruited for the job, and thus inducted into this peculiar guild of athletes who routinely blast themselves more than 30.48m through the air.

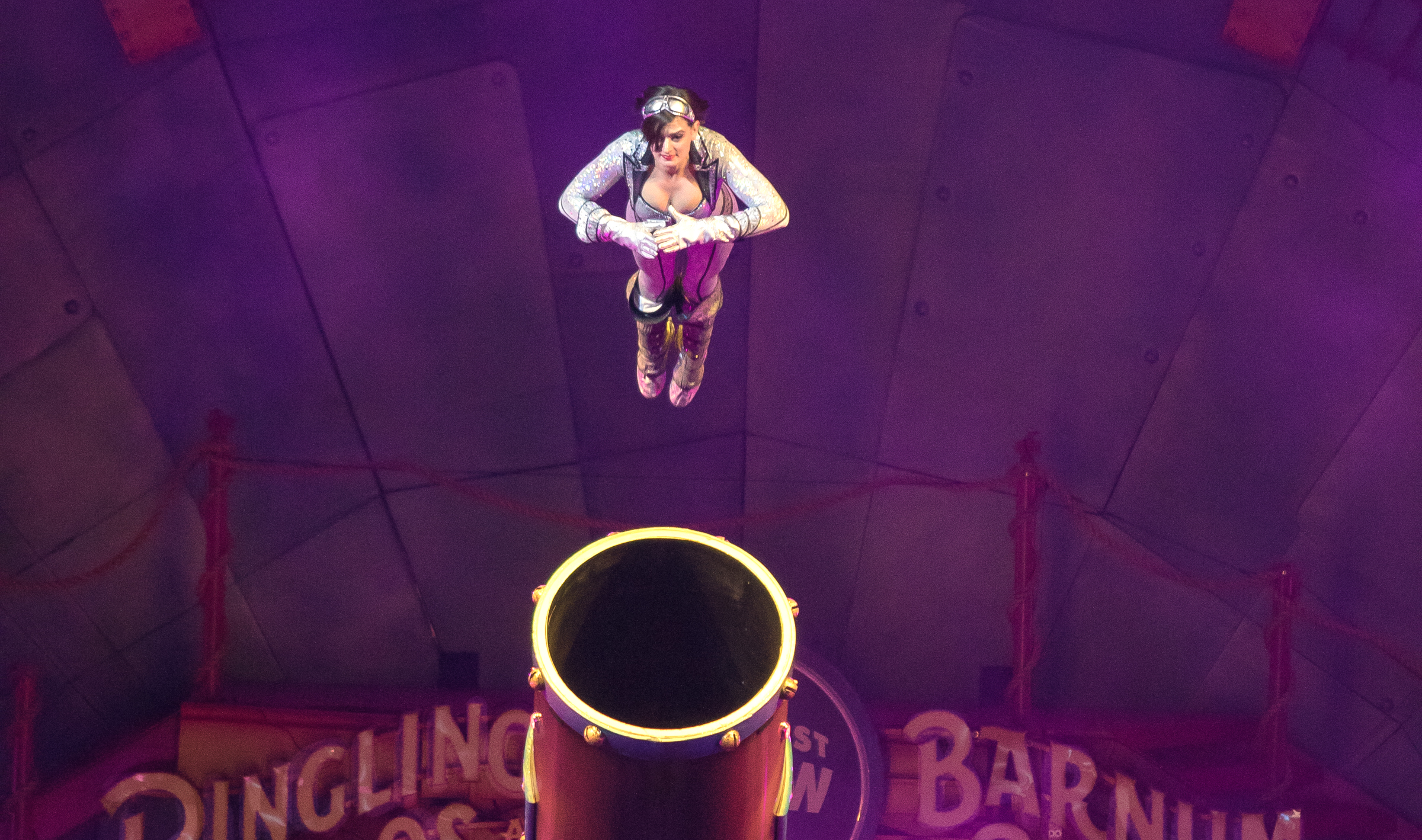

From inside the cannon, Kirby can hear the audience chanting backwards from five. She positions her body in a forearm plank — legs together, butt clenched, arms and elbows tucked — and twines her muscle fibres into rigid formation, anticipating the moment when the platform beneath her will stir to life and heave her skyward with tremendous, brain-draining force.

How does one survive being shot from a cannon? Kirby let us in on some of her secrets. Mostly, it’s a combination of aerial instincts and applied physics — but being a Jedi also helps.

Step One: Become A Jedi

When she was three or four, Kirby discovered Star Wars and immediately set her sights on becoming Luke Skywalker. Her parents, to their credit, did not discourage her gender-bent ambitions. “I want to be Luke Skywalker,” she told them. “Yes, Luke,” they told her back. And for a time she would answer to nothing else.

When she was seven, Kirby enrolled in ballet classes and fell in love with performing. At thirteen, she joined Circus Juventas, a circus school in St. Paul, Minnesota. Circus Juventas didn’t have a cannon, Kirby says, “because the cannon act is kind of dangerous.” Instead, she devoted herself to mastering the flying trapeze, an act that involves zipping through the air at vertiginous heights and perilous speeds. How tame.

Conquering the trapeze was not easy, but nothing satisfies Kirby like a challenge surmounted. “I was afraid of heights, and I had to overcome a lot of fears of falling and being up high and things that kids are normally afraid of,” she says. “Mostly, I love to entertain,” she adds. “And I love to push my boundaries.”

Kirby graduated from high school at 16. Between the ages of 17 and 22, she split her time between a travelling trapeze group and college. By 23, she had earned a psychology degree from the University of Minnesota. Having finished touring and finished school, Kirby says she was looking for something new, something besides trapeze that would get her back on the road. “But I wasn’t sure where to go.”

A short while later, in November of 2013, a friend from the trapeze world reached out to Kirby over social media. The message said that Ringling Bros. was looking for a young female to be shot from a cannon. They wanted to know if Kirby was interested.

She was interested.

The Inner Circle Of Human Cannonballs

Kirby’s first training shot would come a month later, in mid-December. She flew 8.5m. That’s small beer, for a human cannonball. Consider, by comparison, the long jump world record of 8.95m — a record set, by definition, without the aid of heavy artillery.

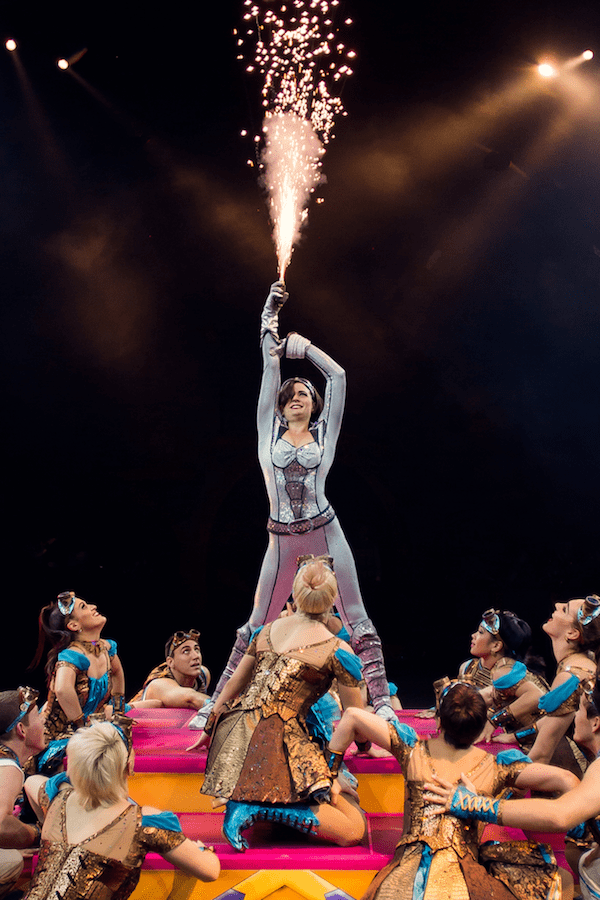

Within a few weeks, however, Kirby was regularly soaring more than 30m through the air. In early January 2014, Kirby opened for Circus XTREME (“extreeeme!” she exclaims, playfully self-aware, during out interview), a travelling show from Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey that showcases the industry’s most breakneck acts. In the span of just two months, Kirby had broken into the highly exclusive cadre of human cannonballs.

Kirby estimates there are no more than a dozen human cannonballs working today, though another recent estimate puts the number at fewer than ten. Her coaches, Brian and Tina Miser, are a husband and wife team famous for lighting one another on fire and shooting in tandem from a double-barreled cannon. Robin and Chachi Valencia — another pair of connubial cannonballs — currently live in Paris and perform on both sides of the Atlantic. Robin’s uncle, David Smith, was a cannonball for over three decades, with his wife, two sons, and three daughters joining him in the act at various points in his career. For years, Smith held the world record for longest human cannonball flight — that was until his son, David Smith Jr., broke that record in March 2011, with a flight of 59.05m. The cannon act, in other words, is primarily a family affair, and has been for the better part of its 150-year history. Interlopers like Kirby are rare.

Why so exclusive? The cannon, says Kirby, is an act built on trade secrets; keeping things familial helps ensure those secrets don’t wander astray. For instance, it is common knowledge that human cannonballs are forcibly expelled from their cannons not by gunpowder (the pyrotechnics are for show), but by compressed air. But nearly everything else about a cannon’s insides are a mystery, unknown to all but those directly involved in its use. Kirby’s coach Brian, who she says has a mind for mechanics, builds all his cannons from scratch, including the one she uses today. The cannons used by Smith Sr. — a former maths teacher — and his family are likewise of his own design. “But there’s no way of knowing if my cannon works the same way as theirs,” says Kirby. She says it’s possible that individual cannons are built very differently from one another, because their mechanistic details are not shared, not even among cannonballs. The details surrounding the cannon’s inner workings, she says, “are the most coveted secrets of the circus.”

You Can’t Wear A Safety Belt

Kirby says being asked to become a cannonball is “kind of unheard of.” So why was she, of all people, ushered in?

Kirby’s coaches, Tina and Brian Miser, told her it was her experience with trapeze, her familiarity with heights, and her outstanding bodily awareness that made her an ideal contender for the cannon act. (The Misers’ daughter, Skyler, was born in 2003, and while she’s grown up with the circus, she’s still too young to trace her parents’ flightpath.)

Beyond being a seemingly qualified candidate, Kirby says there’s not much a person can do to prepare for her first shot. And so you start small. “You can’t wear a safety belt, the way you can with the trapeze,” Kirby says. Usually, when an aerial performer learns a new act, she’s attached to some kind of harness. But for the cannon act there are no training wheels, only weaker propulsive forces. So on your first few flights, your range is shorter. Your height is lower. But when it comes down to it, says Kirby, “you’re still getting shot out of a cannon, completely untethered.”

Early on, Kirby practiced a lot — up to eleven shots a day, she says; but today, the most she’ll do is three. “Every time, you’re taking a big risk,” she says. “You’re using a big piece of equipment with a potentially limited lifespan. I try not to shoot more than is necessary.”

Kirby is right to be cautious; the cannon act’s history is strewn with casualties. Fourteen-year-old Rossa Matilda Richter (stage name Zazel), who launched to stardom in the late 19th Century, was the stunts’s first major headliner. Her career is said to have come to an abrupt end, when she overshot her landing net and broke her back. In 2011, a cannonball named Matt Cranch was performing one of his first shots when his net collapsed. He landed on his head, and later died of his injuries.

The two incidents bookend countless tales of cannon-related death and disfigurement. What records have been kept are, like many circus histories, incomplete and unreliable; but one of the most widely cited statistics on human cannonballs is attributed to late British historian and circus collector Antony Hippisley Coxe. When he stated as much is unclear, but Coxe once claimed that, of 50 human cannonballs known to have attempted the act, more than 30 had perished. It’s difficult to say how many cannonballs have performed throughout history, but Kirby says she would put the number at “a little more than 100 people.” Even if Coxe was exaggerating, and even if Kirby is lowballing, it’s safe to say that “human cannonball” holds a high rank on the list of deadliest professions.

Fortunately, after 15 months and some 550 shots, Kirby is injury free. She attributes her well-being not only to her physical preparation, but the extensive measures that she takes to ensure her safety while performing the act. With the help of her understudy, Nadia Terasova, and Terasova’s husband, Dima Dolgikh (whose job as “trigger person” is to fire the cannon), Kirby inspects and prepares the cannon for every single shot. It’s a process that can take hours to complete.

Do The Maths

At 5’8″, Kirby is tall for a woman, but she only weighs about 61kg. She says her weight needs to be taken into account when determining how high to raise the barrel, and how far she will ultimately launch. She, Terasova, and Dolgikh make these adjustments based on an equation given to them by Brian Miser.

The trio can adjust the cannon to pitch Kirby’s body over a range of heights and distances, but the 7.32m barrel is typically raised to an angle of 39 or 40 degrees, depending on the size of the arena. The cannon is heated to a temperature between 18 and 23 degrees Celsius (presumably, this is to ensure that the pressurised gas used to power the cannon behaves as expected come showtime), and inspected inside and out. A gigantic airbag — not a net — is centered 31.70m from the cannon’s barrel, and tended to by a team of six crew members. Painted on the bag is a target and a smattering of stars — reference points, Kirby says, that she uses to gauge her body position mid-flight.

Preparations and safety checks continue right up until the launch itself, when Kirby lowers herself into the cannon’s mouth and slides to the base of its barrel. Once settled, she checks in with Dima via headset.

“Dima, can you hear me?”

“Yeah, can you hear me?”

“Yep.”

A few seconds later, Kirby tells Dima she’s ready to proceed with the act.

Everything culminates with a five-second countdown, the crowd chanting in unison. Inside the cannon, Kirby runs through her sequence of breath and movement. She recounted it to me in detail, but you can listen for it yourself in the video below, which Kirby recorded on a recent launch:

Five! Kirby inhales. Her breath is big and deep. Four! She exhales sharply, emptying her lungs of air. Three! She sips a slow, steady breath, stopping short when she hears the audience chant Two!

It’s at this point that Kirby assumes a rigid plank position. From her head to her toes, every fibre of her physique is tightly flexed in anticipation of what comes next. The crowd chants “one!” The announcer says “go!” And suddenly Kirby is gaining momentum, accelerating toward the mouth of the cannon. By the time she exits, she’s travelling between 60 and 106km per hour.

The inner workings of these cannons may be closely guarded, but we do know that they pack a wallop. Kirby says the strain on her body is enormous, but that the brunt of it is absorbed by her ankles, knees and glutes. “There’s enough power in there to make peanut butter out of you,” David Smith has said of his home-brew artillery. How much power, exactly? I asked Rhett Allain, a physics professor at Southeastern Louisiana University who has also written extensively on the physics of unconventional artillery, like the cannons used to lob drugs across the U.S./Mexico border.

Above: A photo of a border-defying drug cannon, via the Mexicali Public Safety Department

Allain says we can start with the following kinematic equation. It may look scary to those with a phobia of physics, but it’s actually pretty straightforward:

vf2= v02+ 2a(x — x0)

To translate: The square of Kirby’s velocity exiting the barrel is equal to the square of her velocity at the base of the barrel, plus twice the distance she travels along the barrel multiplied by her acceleration. If we assume a final velocity of 66 mph (29.5 m/s) and an initial velocity of 0 m/s (remember, she’s not moving in any direction while she waits at the base of the barrel), and plug in the length of the barrel (about 7.32 meters), we can solve for Kirby’s acceleration, which comes to to 59.6 m/s 2, or about 6 gs.

The video above claims that Kirby experiences a g-force of 7. That’s certainly possible — likely, even. Our back-of-the envelope calculation makes a few assumptions, but the biggest of these assumptions is the distance that Kirby travels while inside the barrel. For simplicity’s sake, we’ve used the barrel’s overall length, but it’s entirely possible that Kirby, when she lowers herself into the cannon, does not slide down the cylinder’s full, 7.32m extent. Perhaps the launching platform at the base of of the tube is positioned such that she slides only 6.10m. The difference may seem small, but the bodily strain one experiences accelerating to 106km per hour over 6.10m is significantly more than one experiences over 24. In fact, if we plug the former distance into our equation, we get a g-force of around 7.2.

“You want to keep the acceleration down,” says Allain, “because high accelerations kill humans.” A longer barrel keeps your acceleration small, by allowing you build up speed over a greater distance.

The average person can withstand maybe 5 gs before passing out. Granted, Kirby only endures those 6 or 7 gs for a split second, as opposed to, say, the sustained strain that a pilot feels while pulling out of a nose dive (a manoeuvre that can lead to “G-induced Loss of Consciousness,” or G-LOC).

“I’ve heard urban legends of cannonballs losing consciousness in the air,” says Kirby. “I don’t know if those legends are true or if they’re just invented,” she adds. But personally? No. She’ll often feel dizzy, but she’s never blacked out mid-flight.

Stick The Landing

As soon as Kirby exits the barrel, she stretches into a bird-like position, thrusting her arms wide, arching her back, and swinging her legs up and over her head as she reaches the peak of her trajectory. Her fingers, she says, are “super straight, super stretched, and super pretty.”

It’s here, about forty feet in the air, that Kirby’s superhuman aerial abilities come into play. The most dangerous part of the cannon act, she says, is the landing; alighting flat, and face up, is key. It’s also easier said than done. Her elapsed flight time is only about 2.6-seconds. “When you’re that high up, and you have that little time, deciding how to have a controlled landing is not something you do intellectually,” she says. “It’s something your body does on feel.” Kirby honed these skills while training for the trapeze. “After years of executing tricks and missing them, intentionally or by accident, trapeze artists develop instincts where we’ll figure out a way to land on our backs,” she says.

On her way down, Kirby keeps her body elongated until right before she hits the airbag. In the last few hundredths of a second, she tucks her chin to her chest so that she lands flat on her back. If she needs to create more rotation mid-flight, she does a pike, quickly touching her toes before opening her body, like so:

“It’s crazy the way we relate to time,” says Kirby, reflecting on her first flights as a human projectile. “The first, maybe, hundred launches that I did, I remember there being all this prep, and it feeling like an eternity,” she says. “Then I’d climb in, and — fivefourthreetwoonefire! — the next thing I knew I was in the airbag. I wouldn’t even know what had happened.”

But the more flights she logs, the longer those 2.6-seconds of airtime seem. “You put three seconds on a microwave and press start, and it’s nothing,” she says. “But when I’m in the air, lately, it feels like a very, very long time.” Her most recent shots have felt especially slow. “I can see my airbag. I can feel my body from head to toe. I’m completely aware of whether my legs are squeezing together. I can feel the position my fingers are in. It’s a much sharper sensory process,” she says.

But time dilation has its tradeoffs. Kirby says she tries not to dwell on the risks of her profession, but that she’s also “kind of a control freak.” The slowing of time, she says, has only augmented this aspect of her personality. But a big part of the cannon act is acknowledging the unknowable, and being at peace with it.

“When you start to fixate on what could go wrong,” she says, “that’s what’s really dangerous.”

Art by Jim Cooke