Female characters are prominent in scary movies, and not always as helpless victims. Think about the Final Girl, without whom slasher films would not exist, or other kick-arse heroines, like Alien‘s Ripley. Behind the camera, though, you’ll find way more male writers and directors — which is why these horror movies directed by women are worthy of extra celebration.

Near Dark (1987)

American Psycho (2000), directed by Mary Harron

Director Harron (I Shot Andy Warhol) and Guinevere Turner co-wrote the script, adapted from Bret Easton Ellis’ satirical best-seller about a materialistic, appearance-obsessed, serial-killing yuppie. Christian Bale’s note-perfect titular turn forever distanced him from his child-star beginnings, and Harron’s movie — stylish and impressively grisly, while still emphasising the source material’s razor-sharp, pitch-black humour — continues to be influential in so many ways. Where would Mr Robot‘s ruthless, impeccably-dressed, rage-filled Tyrell Wellick be without Patrick Bateman?

The Babadook (2014), directed by Jennifer Kent

Aussie filmmaker Kent also wrote this harrowing tale of a widowed woman (Essie Davis) who’s struggling with raising her rambunctious son alone. Things get way worse when a strange creature emerges from the pages of a children’s book to bring further torment to their lives — but this is no simplistic monster story. The Babadook can be difficult to watch, but it’s masterfully constructed and acted, and the ending offers a huge payoff.

Blood Diner (1987), directed by Jackie Kong

This outstandingly weird horror comedy is an unofficial sequel to gory drive-in classic Blood Feast. But Kong’s ultra low-budget tale of two brothers who become obsessed with gathering body parts as part of a ritual to resurrect an ancient goddess has since earned its own cult following, with good reason. To that end, Blood Diner is part of a handful of exploitation movies to get a recent, blinged-out Blu-ray release as part of the new Vestron Video Collector’s Series.

Buffy the Vampire Slayer (1992), directed by Fran Rubel Kuzui

Before Buffy became a hit TV series, it was a film written by an up-and-coming talent named Joss Whedon, whose script was discovered and developed by director Kuzui. The Sarah Michelle Gellar show has since overshadowed the Kristy Swanson movie, but the latter is not without its own appeal. The winning cast includes Donald Sutherland, Rutger Hauer, Hilary Swank and — not long after his controversial arrest — Paul “Pee-wee Herman” Reubens.

Carrie (2013), directed by Kimberly Peirce, and The Rage: Carrie 2 (1999), directed by Katt Shea

Neither the Carrie remake, nor the original’s ostensible sequel, made as much of an impact as Brian De Palma’s 1976 classic. But it makes sense that women would be interested in further exploring the story of a teenage misfit who unleashes some tremendously alarming telekinetic powers against her cruel classmates and her even crueller mother. The ultimate girl power, really.

Freddy’s Dead: The Final Nightmare (1991), directed by Rachel Talalay

The task of directing the sixth Nightmare on Elm Street film, in which we meet Freddy’s daughter and travel into the Son of a Hundred Maniacs’ mind via the magic of 3D, went to Rachel Talalay. She’d worked on two previous Elm Street films as a producer, but Freddy’s Dead was her directorial debut. Her experience on the film led off a 1991 New York Times article with the cheery title, “Are Women Directors an Endangered Species?“:

When it came time to hire a director for “Nightmare on Elm Street 6” a few months ago, Rachel Talalay was a logical choice. She had, after all, produced Parts 3 and 4 of the gory saga of Freddy Krueger, and they turned out to be the two most successful movies in the teen horror series. But once she actually began work on the project, Ms. Talalay recalled, she “would occasionally get internal memos telling me, ‘Don’t be too girly; don’t be too sensitive.’”

Earlier this year, she was profiled by Entertainment Weekly, which wrote:

[Freddy’s Dead] grossed an impressive $35 million [$AU46 million] but did not prove to be the career launchpad she expected. “Coming off the Nightmare on Elm Street films, the three directors before me all went on to huge action films,” she says. “I wasn’t afforded the same opportunity, and I feel that was absolutely to do with my gender.” In fact, the director of the fourth Freddy movie, Renny Harlin, went on to direct the lavishly budgeted Die Hard 2, while her immediate predecessor in the director’s chair, Stephen Hopkins, was hired to make Predator 2. Talalay’s next film, meanwhile, was the obscure sci-fi thriller Ghost in the Machine.

She later went on to make Tank Girl, which flopped upon release but is now a cult classic, and direct dozens of TV episodes, including Doctor Who and Sherlock. She’s still the only woman to helm any film in any of the major slasher movie franchises.

A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night (2014), directed by Ana Lily Amirpour

Maybe the most unusual film on this list, indie darling A Girl crosses a lot of cinematic boundaries. It’s shot in black-and-white, it’s a spaghetti Western, it’s a vampire movie, it’s a romance, it’s a California-made film told in a foreign language (Persian), it’s a moody feminist tale with a killer soundtrack. And yet somehow, remarkably, it all works.

Humanoids from the Deep (1980), directed by Barbara Peeters

(Warning: The trailer is NSFW.) A rare female Roger Corman protegé, Peeters retains credit on this gleefully sleazy exploitation classic, though the film’s controversial monster-on-human-woman rape scenes were the product of re-shoots done by a male director after Peeters refused (she was fired for her protest).

Jennifer’s Body (2009), directed by Karyn Kusama

Kusama, who’d made Girlfight and Aeon Flux, helmed this high-school horror tale about a cheerleader who is unwittingly transformed into a demonic succubus. The film was released to high expectations, since its script was the first since writer Diablo Cody’s Oscar win for Juno, and it starred Transformers sex kitten Megan Fox. It didn’t exactly set the world on fire back in 2009, but Jennifer’s Body is smart and weird enough to point it toward eventual cult-classic enshrinement.

Near Dark (1987), directed by Kathryn Bigelow

In 2009, Bigelow became the first (and so far, only) woman to win an Oscar for Best Director, when The Hurt Locker took the top prize — besting her former husband James Cameron’s Avatar. But years before Bigelow made The Hurt Locker, Strange Days or even Point Break, she directed Near Dark, which features multiple actors who had also appeared in Cameron’s Aliens the year prior. A violently gorgeous film, Near Dark, which Bigelow co-wrote with Eric Red, may well be the greatest vampire-biker-Western ever. It also has one of horror’s most cult-revered soundtracks, courtesy of Tangerine Dream’s moody synthesizers.

A Night to Dismember (1983), directed by Doris Wishman

Exploitation goddess and John Waters favourite, Wishman’s legacy includes sex-ploitation classics Nude on the Moon (exactly what it sounds like) and Double Agent 73 (the number in the title refers to its lead actress’ impressive bust measurement). One of her last films was this splatter oddity featuring a porn star in the lead; it took years of stop-and-start shooting to complete and makes very little sense, and was never theatrically released. Naturally, it is now a towering cult classic, as the AV Club wrote in the site’s DVD review:

Between the artful nature scenes, the ugly interiors, and the kitchen-sink soundtrack, A Night To Dismember could almost be an avant-garde Guy Maddin homage to wincingly awful cinema. Instead, it’s likely sheer coincidence that A Night To Dismember has become its own entity, a convoluted exercise in viewer endurance that perfectly evokes its title.

Office Killer (1997), directed by Cindy Sherman

After she’s downsized to work-at-home status, a frumpy copyeditor (Carol Kane) offs one of her co-workers, then sorta accidentally becomes a serial murderer. Artist Sherman won a MacArthur “Genius Grant” in 1995; two years later, she made this somewhat uneven horror comedy that is best taken into context as part of her career as a whole. As the New York Times reviewer noted, “the movie itself is almost a Sherman retrospective”, with visual callbacks to the photographs that brought her widespread acclaim.

Organ (1996), directed by Kei Fujiwara

Japanese filmmaker Fujiwara (star of cult-beloved cyberpunk tale Tetsuo: The Iron Man) also wrote, produced and co-stars in this grim, gory tale of organ thieves.

Pet Sematary (1989), directed by Mary Lambert

Lambert would already have an impressive pop-culture legacy even if she had no interest in horror; she was a go-to music video director in MTV’s heyday, helming iconic clips for Janet Jackson (“Nasty”, “Control”) and Madonna (“Borderline”, “Like a Virgin”, “Like a Prayer”), among many others. Fortunately, though, she also made this genuinely eerie Stephen King adaptation — featuring one of the most alarming kiddie maniacs in all of horror-dom — as well as its 1992 sequel.

Ravenous (1999), directed by Antonia Bird

After the original (male) director of this frontier-set black comedy left the production, star Robert Carlyle recommended Bird for the gig. A rough start, but the wild end result is a classic of the cannibal genre.

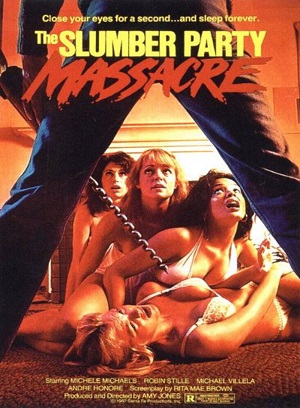

The Slumber Party Massacre (1982), directed by Amy Holden Jones

Novelist Rita Mae Brown (Rubyfruit Jungle) wrote the screenplay for this slasher classic, which you would not know had any feminist leanings (or a killer sense of humour) by simply reading the title or ogling the phallic poster art. The two Slumber Party Massacre sequels were also written and directed by women; Deborah Brock on 1987’s Part II, and Sally Mattison with scripter Catherine Cyran on 1990’s Part III.

Sorority House Massacre (1986), directed by Carol Frank

Frank was a directorial assistant on The Slumber Party Massacre, and ended up writing and directing her own slasher massacre a few years later. It’s not as surprising as Slumber Party, but it certainly delivers on its title.

Trouble Every Day (2001), directed by Claire Denis

Acclaimed art-house director Denis (Beau travail, White Material) made this erotic and exquisitely gruesome horror movie with Vincent Gallo at the height of his fame (between Buffalo ’66 and The Brown Bunny). He plays a newlywed who just can’t leave his sexy ex alone… or set aside his thirst for human blood.

The Velvet Vampire (1971), directed by Stephanie Rothman

Rothman, another Corman discovery, is probably best-known for 1970’s The Student Nurses, which balances feminism and exploitation with incredible adroitness. But The Velvet Vampire, starring the glamorous Celeste Yarnell as the titular seducer, is not without its own charms. In a 2007 interview, Rothman — whose experience with Corman seems to have been overall very positive — reflected on what it was like working within the exploitation genre.

I was never happy making exploitation films. I did it because it was the only way I could work. While I do not object to violence or nudity in principle, the reason audiences came to see these low-budget films without stars was because they delivered scenes that you could not see in major studio films or more supposedly ambitious independent American films. (Today, of course, you can see these scenes and more, but we are talking about standards operative in the mid-nineteen sixties to seventies when I was working.) Exploitation films required multiple nude scenes and crude, frequent violence. My struggle was to try to dramatically justify such scenes and to make them transgressive, but not repulsive. I tried to control this through the style in which I shot scenes. That was one of my greatest pleasures, determining how my style of shooting could enhance the content of a scene.