Scientists have learned that upwards of 25 per cent of all people who become infected with Ebola show none of the typical symptoms. The finding suggests the recent West African Ebola Epidemic was more widespread than previously thought, and that new methods need to be developed to diagnose and contain the dreaded virus during an outbreak.

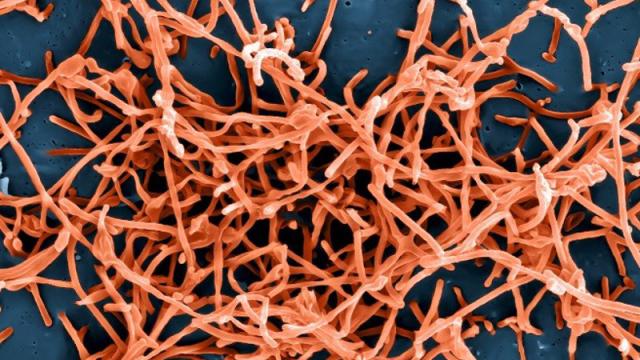

The Ebola virus. (Image: NIAID)

Typically, Ebola produces a panoply of symptoms, including fever, unexplained bleeding, headache, muscle pain, rash, vomiting, diarrhoea, breathing problems and difficulty swallowing. As is well documented, this virus is particularly deadly, killing between 10 to 80 per cent of people who exhibit these symptoms (the statistical spread reflects the divide between those who have access to intensive care and those who don’t).

But as a new study published in PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases shows, a significant portion of people who contract Ebola don’t show any of the typical signs, meaning they’re asymptomatic, or their symptoms are relatively mild and not wholly reflective of how the virus affects most people. In other words, they have “minimally symptomatic infections”.

Prior to the new study, scientists suspected that Ebola, like many other viruses, might not always manifest in the same predictable way. The new study, led by Gene Richardson, a PhD candidate in anthropology at Stanford University and a former fellow in the Division of Infectious Diseases and Geographic Medicine, now confirms this suspicion, while providing an actual estimate for the rate of asymptomatic and minimally symptomatic infections in Ebola patients.

Following the recent West African Ebola Epidemic, Richardson and his colleagues went back to the rural village of Sukudu in Sierra Leone, a major hotspot for the outbreak. The village, which is home to 900 residents, recorded 34 cases of Ebola during the epidemic, including 28 deaths. Working with a local physician, Richardson’s team tested 187 men, women and children from Sukudu who had likely been exposed to Ebola, either because they lived in the same household or shared a public toilet with a person known to have had the disease.

Of these, 14 were found to carry an antibody to Ebola — a sure sign that they were infected at some point. A dozen of these villagers said they had no symptoms of the disease, while two recalled having a fever at the time of the outbreak.

It’s certainly possible that some of these villagers had full-blown symptoms but were fearful of admitting the truth to doctors. Consequently, more research with a larger sample pool will have to be performed. However, Richardson and his colleagues think they’re onto something, and that the villagers were probably telling the truth.

Importantly, the researchers aren’t sure if an asymptomatic person with Ebola can transmit the virus. “They were not passing it along in the usual way, through vomiting or diarrhoea,” noted Richardson in a statement. “It’s unclear if they can pass it along it sexually.”

More research is needed to determine if Ebola can be spread by a person who shows no or very few symptoms, but it’s a very distinct possibility. A person with an infection still has Ebola particles in their body, which could find a way to “jump” to another person. But without the typical symptoms, it’s certainly much more difficult. As Richardson noted, the virus might be transmitted sexually, though that still needs to be proven in an asymptomatic individual.

Richardson and his colleagues are now working in other villages in Sierra Leone to get a better handle on the true number of people affected during the crisis. But if the figure of 25 per cent is correct — and if Ebola can spread via asymptomatic people (that’s still a big if) — that presents a massive headache for health officials.

Adding insult to injury, the Ebola virus mutated into a deadlier form during the last outbreak, showing an ability to quickly adapt to human biology and become even more virulent. Taken together, these new findings show that Ebola spreads more rapidly and more broadly through a population, highlighting the need for new detection and containment techniques for when the next outbreak hits.