Researchers in the Netherlands have successfully tested a brain implant that allows a patient with late-stage Lou Gehrig’s disease to spell messages at the rate of two letters per minute.

Image: Brain Center Rudolf Magnus, University Medical Center Utrecht

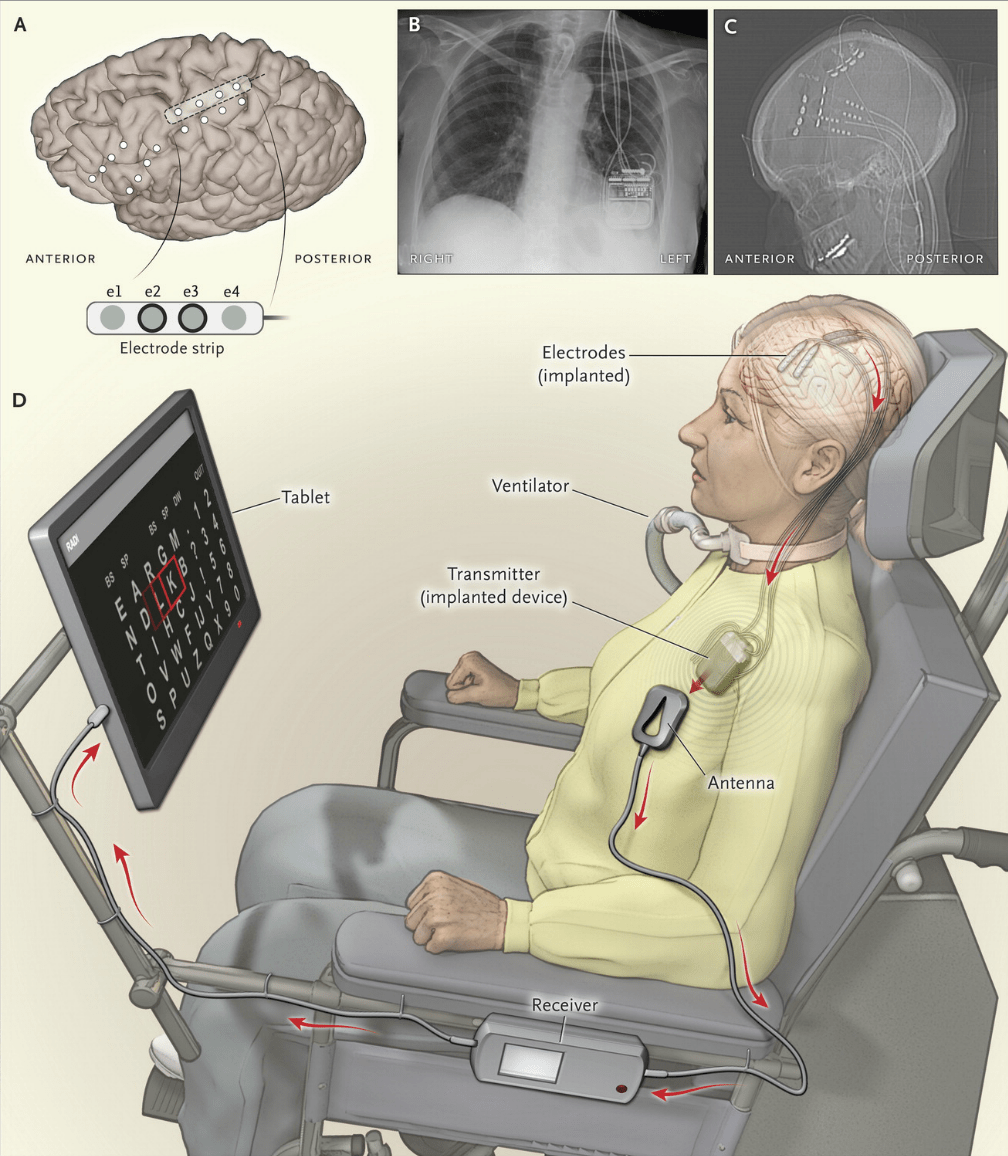

The new system was tested on Hanneke De Bruijne, a 58-year-old woman in the late stages of Lou Gehrig’s disease, also known as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Unable to move any part of her body aside from her eyes, De Bruijne used the wireless computer-brain interface to identify letters by imagining that she was using her right hand. She can now use the system at home to communicate with family and caregivers.

Prior to the brain implant, De Bruijne used an eye-tracking system to communicate, but it had to be recalibrated every time light levels in her surroundings changed. The new system is far more reliable and autonomous, and it can be used at home without any extra help. At a rate of two letters per minute, typing is still excruciatingly slow. But it’s an important proof-of-concept showing that patients can use the system on their own and without much technical support. In future, the system could be adapted to stroke patients or quadriplegics.

Image: University Medical Center Utrecht in the Netherlands

“This is a major breakthrough in achieving autonomous communication among severely paralysed patients whose paralysis is caused by either ALS, a cerebral hemorrhage or trauma,” noted Professor Nick Ramsey, professor of cognitive neuroscience at the University Medical Center (UMC) Utrecht, in a statement. “In effect, this patient has had a kind of remote control placed in her head, which enables her to operate a speech computer without the use of her muscles.”

Four sensor strips were implanted on De Bruijne’s motor cortex (the part of the brain that controls voluntary movements). Whenever she thinks about bringing her right thumb and ring finger together, the chip detects a small electrical spike. A computer receives these signals over wireless, and interprets it as a “brain click”.

To type specific letters, De Bruijne uses a tablet display that features four rows of letters. As a red cursor moves from left to right across the alphabet (plus some functions like deleting a letter or word, and selecting words based on the letters she has already spelled), she executes a brain click when the desired letter is highlighted. The process repeats until an entire word is spelled out and spoken by the computer’s speech program.

Using the system, patients like De Bruijne can express their desires or communicate problems, such as an itch, an excessive buildup of saliva or problems with a ventilator. Looking ahead, the researchers would like to test the system on two more patients before undertaking a large-scale trial.