Humans have been eating other humans since the beginning of time, but the motivations behind this macabre practice are complex and often unclear. Some anthropologists say prehistoric cannibals were just trying to grab a nutritious snack, but new research shows that human flesh — as tasty as it is — doesn’t pack the same caloric punch as wild animals. In other words, cannibalism wasn’t worth the trouble given alternatives.

Illustration: Jim Cooke/Gizmodo

A new study published in Scientific Reports is the first to provide a caloric breakdown of the human body — from tip to toe and all the scrumptious parts in between — to assess the motivations of prehistoric cannibals. The sole author of the study, archaeologist James Cole from the University Brighton, used this data to compare the caloric value of humans to other animals around during this prehistoric time. In general, he found that the human body has the same nutritional value — in terms of fat and protein — of equally-sized creatures, but when compared to bigger prey, such as mammoths and woolly rhino, humans offered significantly fewer calories. The study suggests that any interpretation of cannibalism during the Paleolithic Era has to take other considerations into account, such as cultural, social and religious practices.

“Cannibal feast on the Island of Tanna, New Hebrides,” by Charles E. Gordon Frazer (1863-1899). (Image: CC)

During the Paleolithic Era — a 2.6 million-year-long period that ended 10,000 years ago — some bands of ancient humans and hominins (that is, extinct human species and all our immediate ancestors) engaged in cannibalistic practices, eating the flesh of their own. We know this from the clues they left behind — human remains exhibiting signs of defleshing, deliberate cut marks around the joints, human chewing, and the cracking of bones to get at the marrow.

The reasons for cannibalism vary, ranging from religious rites and mortuary practices through to the intimidation of enemies and weeding out the sick and elderly. Some anthropologists, however, believe that cannibalism was done primarily for nutritional reasons (see examples here, here and here). But there’s very little evidence to support this claim, and there hasn’t been a good way for scientists to quantify the nutritional benefits of cannibalism. Cole’s study is the first to correct this oversight.

“For the first time — as far as I am aware — someone has constructed a calorific template for the human body,” Cole told Gizmodo. “This was done in order to try and get a better understanding for the motivations behind episodes of Palaeolithic cannibalism.”

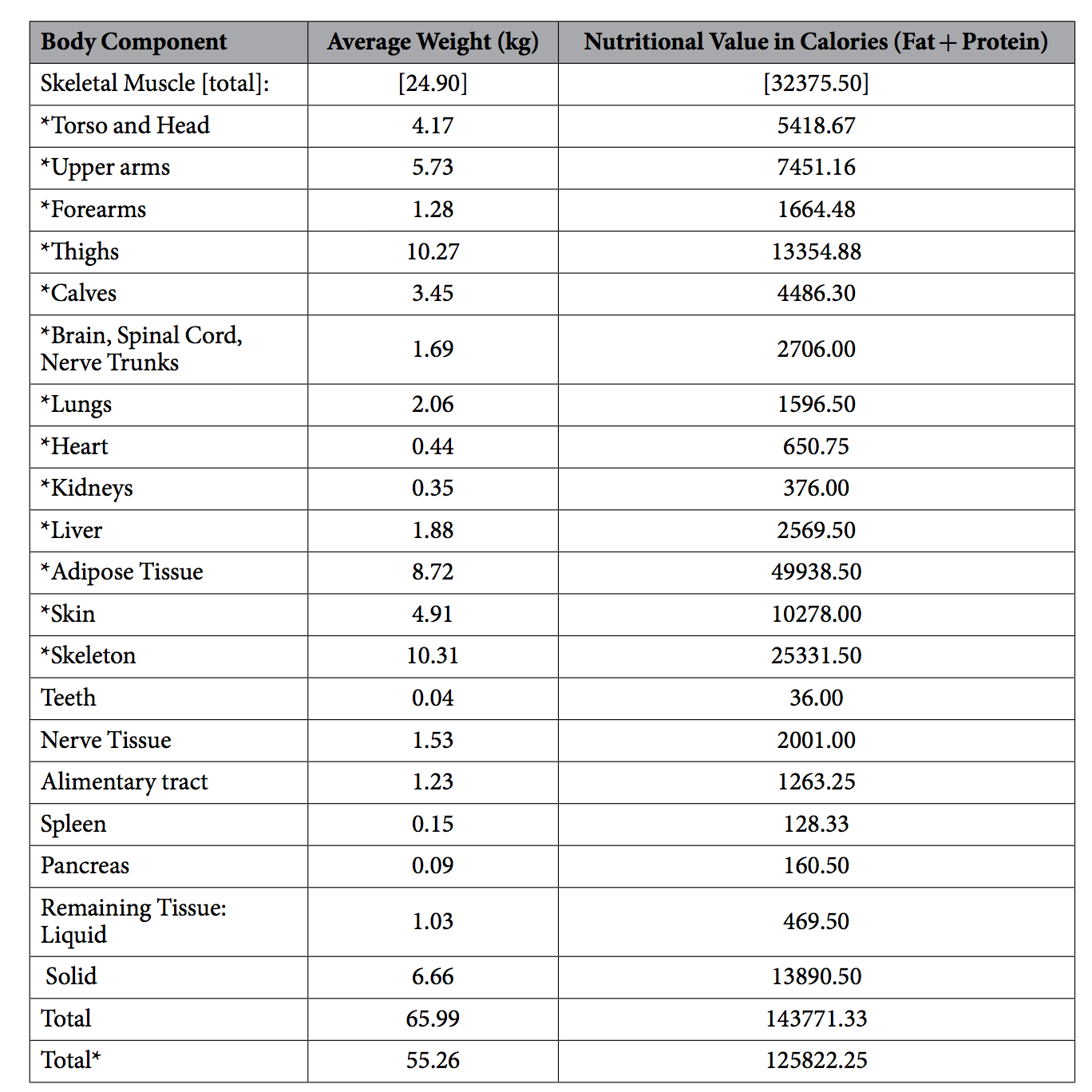

To create this grim and unconventional nutritional label, Cole took average weights and calorie values (from fat and protein) for each part of the body. This was done via a chemical composition analysis, and it was performed on four male individuals. The resulting data pertains to modern humans, who admittedly aren’t exactly like Palaeolithic humans, or Neanderthals, whose large frame allowed for slightly more muscle mass than Homo sapiens. Still, it’s a safe bet these values are close — it isn’t like ancient humans and hominins were 10 times larger or smaller than we are today.

Mmmm, adipose tissue. (Credit: James Cole/Scientific Reports)

A quick scan of the chart shows that the total muscle mass of a 66kg adult male consists of about 32,376 calories (135,461kJ). That’s enough to sustain about two people for a week. Some of the more nutritious body parts include the liver (2569 calories/10,749kJ), thighs (13,354 calories/55,873kJ) and the collective mass of adipose or fat tissue (a whopping 50,000 calories/209,200kJ). Teeth are a light snack, at 36 calories (151kJ) per 40g. Good to know in a pinch.

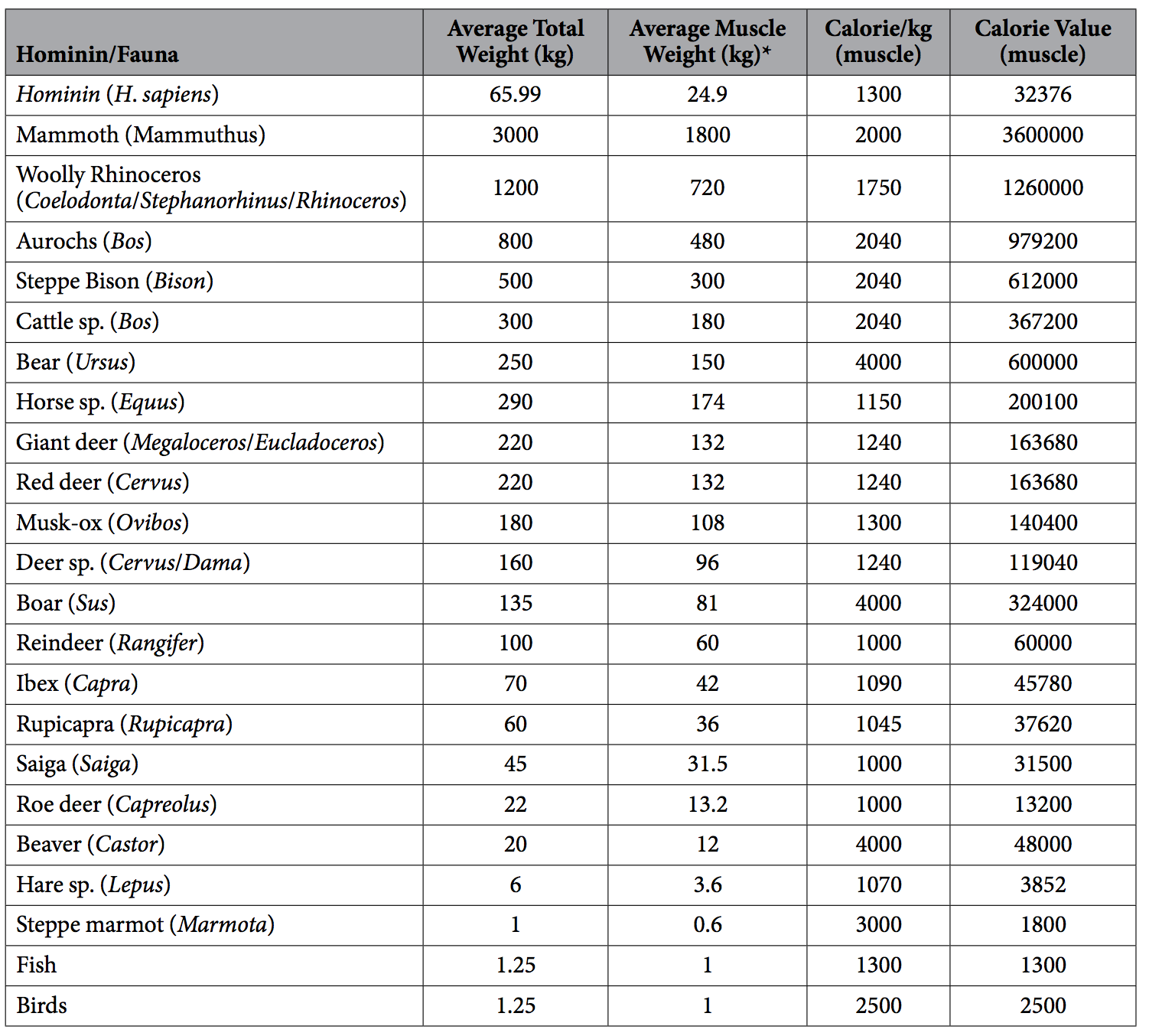

Armed with this chart, Cole compared these calorific values to those of animal species whose remains were found at the sites of Palaeolithic cannibals, including mammoths, wooly rhinos, auroch, bison, boar, rabbits and various species of deer. He found that humans produce nutritional values that are comparable to animals of similar size and weight — but the human body, not surprisingly, yields significantly fewer calories than the big animals. In the most extreme case, the muscle mass of a mammoth contains an estimated 3.6 million calories (15 million kJ). A 3000kg mammoth could sustain 200 humans for a week from its muscle mass alone. Other big game include woolly rhino (1.2 million calories/5 million kJ), bison (612,000 calories/2.5 million kJ), and giant deer (163,680 calories/684,837kJ).

Caloric content of animals that lived alongside ancient humans. (Credit: James Cole/Scientific Reports)

“From my study I have shown that humans and hominins are not particularly high in calorific content when compared to other fauna that are regularly exploited by our hominin ancestors such as a horse for example,” said Cole. “Therefore, I would question whether the motivation for the cannibalism act was due to nutritional needs or perhaps something more socially driven such as resource defence or something along the lines.”

An underlying assumption of the paper is that it made more sense from a caloric intake perspective for our ancestors to hunt or trap animals than feed off the human population, whether those humans were outsiders or from the same clan.

“I would argue that to hunt or capture a member of your own species — who is as intelligent as you, and as able to fight back as you — is probably harder than hunting another faunal species such as a horse,” explained Cole. “Both are obviously difficult and challenging acts, but I suspect hominins may have been more challenging. In addition, you only need to kill one horse to get the same or more calories than six to four individual hominins.”

That said, prehistoric humans likely resorted to cannibalism as a survivalist measure during times of drought or famine. Cole says we cannot rule this type of cannibalism out entirely. He also says we need to embrace the idea that other human species may have been as varied and as complex as our own species with regards to cannibalism. “Neanderthals, for example, were extremely complex behaviourally, they were a symbolic species with jewellery production, cultural diversity in terms of stone tool manufacture, and they had a complex attitude to the burial of their dead,” he said. “Why would they not have an equally complex attitude to the acts of cannibalism?”