In the summer of 2015, Alexandra Franco got a letter in the mail from a company she had never heard of called AcurianHealth. The letter, addressed to Franco personally, invited her to participate in a study of people with psoriasis, a condition that causes dry, itchy patches on the skin.

Image by Jim Cooke

Franco did not have psoriasis. But the year before, she remembered, she had searched for information about it online, when a friend was dealing with the condition. And a few months prior to getting the letter, she had also turned to the internet with a question about a skin fungus. It was the sort of browsing anyone might do, on the assumption it was private and anonymous.

Now there was a letter, with her name and home address on it, targeting her as a potential skin-disease patient. Acurian is in the business of recruiting people to take part in clinical trials for drug companies. How had it identified her? She had done nothing that would publicly associate her with having a skin condition.

When she googled the company, she found a lot of people who shared her bewilderment, complaining that they had been contacted by Acurian about their various medical conditions. Particularly troubling was a parent who said her young son had received a letter from Acurian accurately identifying his medical condition and soliciting him for a drug trial — the first piece of mail he’d had addressed to him besides birthday cards from family members.

Acurian has attributed its uncanny insights to powerful guesswork, based on sophisticated analysis of public information and “lifestyle data” purchased from data brokers. What may appear intrusive, by the company’s account, is merely testimony to the power of patterns revealed by big data.

“We are now at a point where, based on your credit-card history, and whether you drive an American automobile and several other lifestyle factors, we can get a very, very close bead on whether or not you have the disease state we’re looking at,” Acurian’s senior vice president of operations told the Wall Street Journal in 2013.

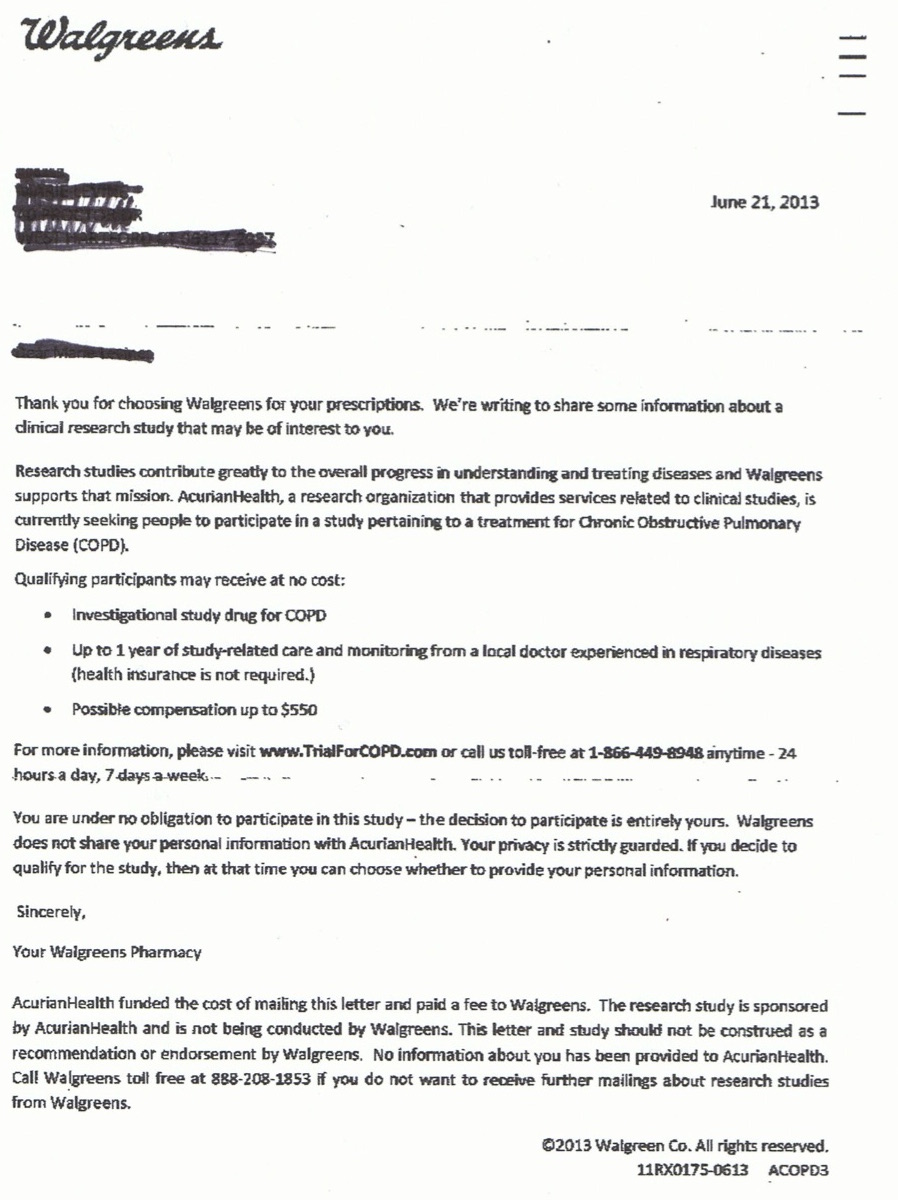

Yet there’s some medical information that Acurian doesn’t have to guess about: The company pays Walgreens, which uses a privacy exemption for research, to send recruitment letters to its pharmacy customers on Acurian’s behalf, based on the medications they’re using. Under this arrangement, Acurian notes that it doesn’t access the medical information directly; the customers’ identities remain private until they respond to the invitations.

And that is not the entire story. Our investigation found that Acurian may also be pursuing people’s medical information more directly, using the services of a startup that advertises its ability to unmask anonymous website visitors. This could allow it to harvest the identities of people seeking information about particular conditions online, before they have consented to anything.

A letter sent out to a Walgreens customer in Connecticut on Acurian’s behalf. It invited her to visit a generic sounding website for people with pulmonary disease. At the time, she had a prescription from Walgreens for asthma.

If you’re suddenly thinking back on all of the things you’ve browsed for online in your life and feeling horrified, you’re not alone.

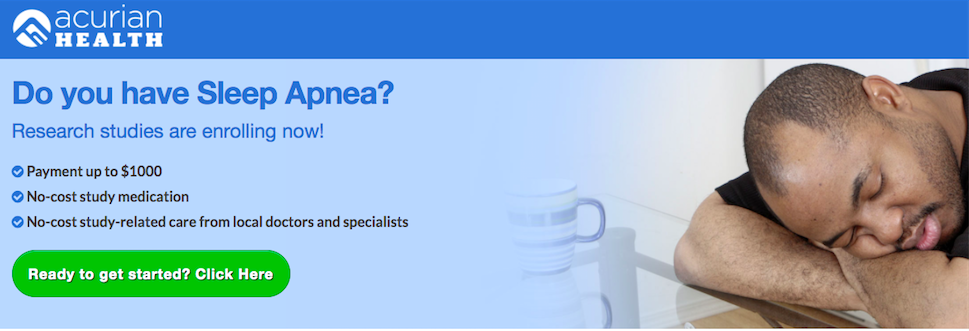

AcurianHealth has created dozens and dozens of generic sounding websites for the trials they’re recruiting for: www.trialforCOPD.com, www.studiesforyourarthritis.com, and www.kidsdepressionstudy.com are a few examples of the many websites they own. The sites all feature stock images of people in distress, sometimes include AcurianHealth’s logo, and include promises of up to $US1000 ($1316) for participating, depending on the study.

An example of one of the Acurian sites, www.sleepapneastudies.com

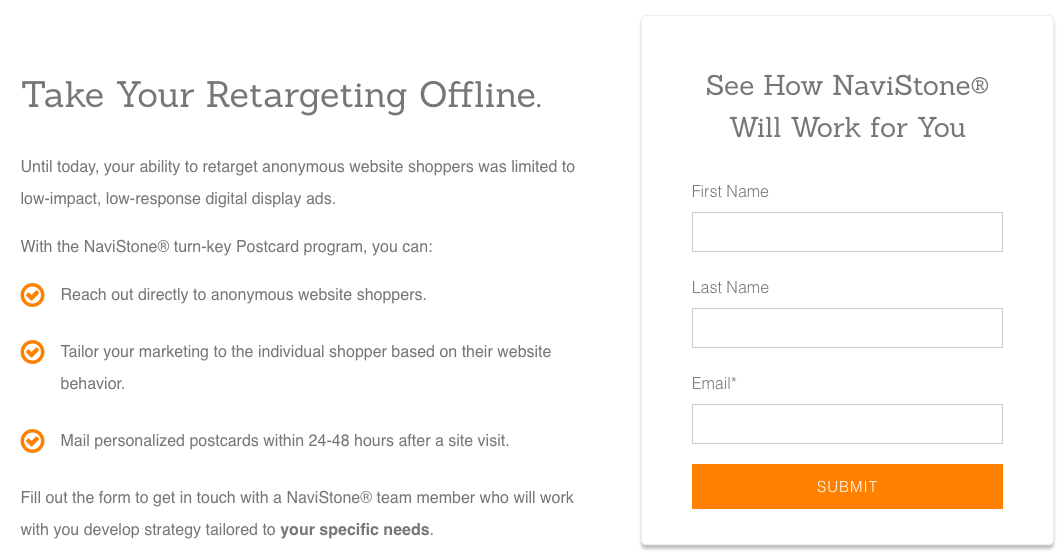

Out of view, some of these sites include something else: Code from a company called NaviStone — which bills itself as a specialist in matching “anonymous website visitors to postal names and addresses”. So if a person is curious about one of those letters from Walgreens, or follows one of Acurian’s online ads, and visits one of Acurian’s generic disease-specific sites, their identity could be discovered and associated with the relevant condition.

NaviStone says it can send personalised mail to anonymous website visitors with a day or two of their visit.

This tracking function undermines what’s supposedly a formal separation between Walgreens customer data and Acurian’s recruitment. If Walgreens sends out a bunch of letters to customers taking certain medications, and those customers then visit the generic website controlled by Acurian provided in the letter, Acurian can infer its wave of new visitors are taking those medications — and, if NaviStone delivers on its promise to identify visitors, Acurian can see who they are.

Walgreens gives itself permission to use customers’ health information for “research” purposes, which would include clinical trials, in its privacy policy. It’s been working with Acurian since at least 2013, and in 2015, Walgreens announced it was “leveraging” its 100 million customer database to recruit patients directly for five major drug companies.

When asked about its partnership with Acurian, Walgreens spokesperson Scott Goldberg pointed me to a Walgreens FAQ page about clinical trials. It states that Walgreens doesn’t share health information with third parties without permission, but that a third party may “receive your information if you contact the web-site and/or toll-free number in the letter to seek more information about the clinical trial”.

The question is whether users will know that one of Acurian’s websites has received their information — even if they haven’t necessarily agreed to submit it. NaviStone, an Ohio-based business spun out from the marketing firm CohereOne last year, claims to be able to identify between 60 and 70 per cent of anonymous visitors to the websites that use its services.

When we contacted the firm last month to ask how it does this, Allen Abbott, NaviStone’s chief operating officer, said by phone that talking about how its technology works is “problematic”.

“A lot of our competitors would love to know how we made it work,” Abbott said. “We have an advantage that we would be silly to reveal.”

We asked whether the company had thought about the privacy implications involved in identifying people visiting a website for sensitive reasons, and whether there were certain customers the company wouldn’t work with.

“Our business is almost entirely e-commerce, helping retailers sell to their customers,” he said. “There was one site that came into our radar that was adult-related material that we decided not to pursue.”

We then described what Acurian does.

“We don’t work with anyone like that,” he said.

We explained that the call was because we’d found NaviStone’s code on AcurianHealth sites.

“It’s possible,” he then said. “We have a lot of customers.”

But Abbott insisted that NaviStone had found a “privacy compliant way” to identify anonymous website visitors — again saying he couldn’t describe it because it was a proprietary technology.

When we analysed the NaviStone code on Acurian’s sites, we found one way that NaviStone’s technology works: It collects information as soon as it is entered into the text boxes on forms, before the person actually agrees to submit it. When we typed a test email address in the “Join Us” page on Acurian’s site, it was immediately captured and sent to the company’s servers, even if we later chose to close the page without hitting the “Send” button on the form.

In fact, the information was collected before we got to the part of the form that said, “Your privacy is important to us. By selecting this box, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, and agree that we contact you by phone using automated technology or other means using the information you provided above regarding research studies.”

“If I haven’t hit send, what they seem to be doing almost seems like hacking,” said Lori Andrews, a law professor at the Chicago-Kent School of Law. “It’s similar to a keystroke tracker. That could be problematic for them.”

Ryan Calo, a law professor at the University of Washington, said this clearly violates a user’s expectation of what will happen based on the design of the site. “It’s not that they lied to you with words, but they have created an impression and violated that impression,” said Calo who suggested it could violate a US federal law against unfair and deceptive practices, as well as laws against deceptive trade practices in California and Massachusetts. A complaint on those grounds, Calo said, “would not be laughed out of court.”

When we followed up with NaviStone’s Abbott by email, he insisted that the company doesn’t send any data to Acurian.

“We don’t send any email for Acurian, or pass along any email addresses to them or use their email addresses in any way or manner,” said Abbott by email. “If we are indeed inadvertently collecting email addresses, we will fix immediately. It’s not what we do.”

But when we reviewed dozens of other companies’ websites that were using NaviStone’s code, they were also collecting email addresses. After a month of repeated inquiries to NaviStone and to many of the sites using its code, NaviStone last week stopped collecting information on the site of Acurian and most of its other clients before the “Submit” button was pressed.

“Rather than use email addresses to generate advertising communications, we actually use the presence of an email address as a suppression factor, since it indicates that email, and not direct mail, is their preferred method of receiving advertising messages,” said Abbott by email. “While we believe our technology has been appropriately used, we have decided to change the system operation such that email addresses are not captured until the visitor hits the ‘submit’ button.”

Asked about its partnerships with Walgreens and NaviStone, Acurian declined to be interviewed.

“As a general policy based on our confidentiality agreements with our business partners, I hope you will understand that Acurian does not discuss its proprietary business strategies,” said Randy Buckwalter, a spokesperson for PPD, the corporate parent of Acurian, by email.

Buckwalter told us Acurian would provide a fuller response to what is reported here, but never provided it.

Kirk Nahra, a partner at the law firm Wiley Rein who specialises in health privacy law, said there’s nothing really wrong with Walgreens sending out letters to customers on Acurian’s behalf. “But that second situation, where I go to look at the website and at that point they have some way of tracking me down, their ability to track me down at that point is troubling,” Nahra said.

Nahra said there was a potential legal issue if the company fails to disclose this in its privacy policy, and that it could lead to a class action lawsuit. Acurian’s privacy policy only talks about getting information from “data partners” and collecting expected information from website visitors, such as IP addresses — which can be used to track someone from website to website, which is why it’s a good idea to use technology that obscures your IP address, such as Tor or a VPN.

The ability to identify who is sick in America is lucrative. Acurian offers a collection of case studies to potential customers in which it discloses what it bills: $US4.5 million ($5.9 million) for recruiting 591 people with diabetes; $US11 million ($14.5 million) for 924 people with opioid-induced constipation; $US1.4 million ($1.8 million) for 173 teens with ADHD; and $US6 million ($7.9 million) for 428 kids with depression.

Acurian claims to have a database of 100 million people with medical conditions that could be of interest to drug companies, and it says that all of those people have “opted-in” to be contacted about trials. In addition to internet complaints suggesting otherwise, the US Federal Trade Commission has received more than 1000 complaints over the last five years from consumers who say the company has contacted them without consent; some complainants also wanted to know how the company had found out about their medical conditions.

Acurian has also faced a slew of class-action lawsuits in Florida, Texas and California from plaintiffs who say the company had illegally robocalled them about clinical trials, placing multiple automated calls to their home without getting their permission first, a violation of US federal law. Acurian denied wrongdoing in court filings, saying its calls are not commercial in nature and that the plaintiffs had opted in, but settled all the suits out of court.

Alexandra Franco certainly didn’t opt in to be contacted for clinical trials. She doesn’t have psoriasis or any prescriptions for a skin condition. When she looked back at her browsing history, it appeared that the only website she visited as part of her search was the mobile version of WebMD.com.

“While Acurian had purchased display advertising from WebMD in 2010, we have never hosted a program for them in which personal information was collected or shared,” said WebMD in a statement. “Under our Privacy Policy we do not share personal information that we collect with third parties for their marketing activities without the specific consent of the user. In this case, it appears that the user did not even provide any personal information to WebMD.”

“Doing a search on your mobile device means you are incredibly re-identifiable,” said Pam Dixon of the World Privacy Forum, referring to the fact that a mobile device provides more unique identifiers than a computer typically does.

Franco doesn’t understand exactly how Acurian got her information, but said that the letter was sent to her home addressed to “Alex Franco”, a version of her name that she only uses when doing online shopping. When she sent an inquiry to Acurian, the company told her it got her name from Epsilon, a data broker, “based on general demographic search criteria”.

“Epsilon specialises in compiling mailing lists based on generally available demographic information like age, gender, proximity to a local clinical site and expressed interests,” said the company in an email. “We sincerely regret any distress you may have experienced in thinking your privacy may have been compromised, and we hope this letter has assured you that nothing of the kind has occurred.”

Franco didn’t feel particularly assured. Epsilon lets consumers make a request to find out what information the data broker has on them; in response to her request, Epsilon told Franco by letter that it has her home address and information about her likely income, age, education level, and length of residence, as well as whether she has kids — none of which would seem to indicate dermatological issues.

At the end of our investigation, we still don’t know exactly how Franco was identified as possibly having a skin condition. Given the many players involved and the fact that we can’t see into their corporate databases means we can only make reasonable assumptions based on the outcome.

It’s the online privacy nightmare come true: A company you’ve never heard of scraping up your data trails and online bread crumbs in order to mine some of the most sensitive information about you. Acurian may try to justify the intrusion by saying it’s in the public interest to develop new drugs to treat illnesses. But tell that to the person shocked to get a letter in the mail about their irritable bowels.

Yes, we found that person. Bret McCabe complained about it on Facebook. He got the letter in 2012 after regularly buying both anti-diarrhoea medicine and laxatives at Walgreens and Rite-Aid for a family member dealing with chronic pain issues.

“The creep factor of the specificity is what I found particularly grating,” said McCabe by phone. “It’s one thing to get spam about erectile dysfunction or refinancing your car loan, but in this case, it seemed like they specifically knew something about me. It was meant for me and me only.”

The privacy scholar Paul Ohm has warned that one of the great risks of our data-mined society is a massive “database of ruin” that would contain at least one closely-guarded secret for us all, “a secret about a medical condition, family history, or personal preference… that, if revealed, would cause more than embarrassment or shame; it would lead to serious, concrete, devastating harm.”

Acurian has assembled one of those databases. As with all big databases, the information doesn’t even have to be accurate. So long as it gets enough of its letters to the right people, the recruitment company doesn’t need to care if its collection efforts misidentify Franco as a psoriasis patient or otherwise incorrectly link people, by name, to medical conditions they don’t have.

This is the hidden underside of the browsing experience. When you’re surfing the web, sitting alone at your computer or with your smartphone clutched in your hand, it feels private and ephemeral. You feel freed to look for the things that you’re too embarrassed or ashamed to ask another person. But increasingly, there is digital machinery at work turning your fleeting search whims into hard data trails.

The mining of secrets for profit is done invisibly, shrouded in the mystery of “confidential partnerships”, “big data” and “proprietary technology”. People in databases don’t know that dossiers are being compiled on them, let alone have the chance to correct any mistakes in them.