Hidden within our genetic code is a vast treasure trove of personal information about our health, relationships, personality and family history. Given all the sensitive details that a DNA test can reveal, you would hope that the people and programs handling that information would be vigilant in safeguarding its security. But it turns out that isn’t necessarily the case.

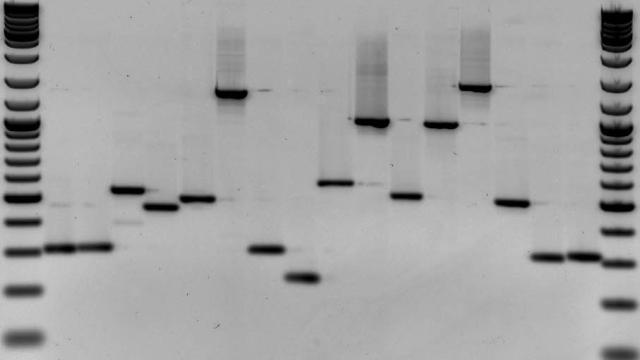

Image: Wikimedia Commons

In a new study that will be presented next week at the 26th USENIX Security Symposium in Vancouver, University of Washington researchers analysed the security practices of common, open-source DNA processing programs and found that they were, in general, lacking. That means all that super-sensitive information those programs are processing is potentially vulnerable to hackers. If you think identity fraud is bad, imagine someone hacking your genetic code.

“You can imagine someone altering the DNA at a crime scene, or making it unreadable. Or an attacker stealing data or modifying it in a certain way to make it seem like someone has a disease someone doesn’t actually have,” Peter Ney, a co-author of the peer-reviewed study and PhD student at the school’s Computer Security and Privacy Research Lab, told Gizmodo.

Now, this doesn’t mean that if you’ve used a DNA testing service you should start panicking. Reading DNA is far cheaper today than it’s ever been in the past, but it’s still something that requires a big, expensive machine. Writing DNA is even more difficult. Those things create a big hurdle for anyone who might be interested in hacking into sequencing software.

“In the future,” though, said co-author Lee Organick, “that might not always be the case.”

Right now, for example, machines from Illumina can sequence DNA for about $US1000 ($1269), but the company has promised that in the next decade it will do it for $US100 ($127).

It doesn’t take much to imagine how exposing someone’s genetic information could be harmful. Hackers could tamper with crime scene evidence, or expose private health information or details about someone’s family relationships. Imagine Wikileaks leaking that a political candidate had, say, a strong likelihood of developing Alzheimer’s. Could that influence how people vote? In the US, the (pretty weak) anti-genetic discrimination laws can’t do much to protect people if their information is exposed illegally.

The University of Washington researchers looked specifically at the programs that process and analyse DNA after sequencing — those are the algorithms that interpret your genetic information and tell you, say, whether you’re at risk to develop a certain disease. Companies such as 23andMe or Ancestry.com use similar programs, as do the many DNA testing start-ups like those in Helix’s new launched DNA ‘app store.’ Researchers looked at commonly used, open-source versions of those programs. Many, they found, were written in programming languages known for having security issues. Some also contained specific vulnerabilities and security problems.

“This basic security analysis implies that the security of the sequencing data processing pipeline is not sufficient if or when attackers target,” they wrote.

Separately, the researchers looked at whether DNA being used to store non-genetic information might be vulnerable to malware. They found that it was. While this threat reads a little more science fiction, it’s also concerning. It means that you could program malware into DNA and then use it to take control of a machine being used to analyse it. Hackers could, in theory, fake a blood or spit sample and then use it to gain access to computer systems when those samples are being analysed.

That risk, though fascinating, is little more than theoretical. Encoding DNA with information is an extremely nascent pursuit, and code like that instructing a computer to execute a task is at risk for being made unreadable by all the other noise in a DNA sequence. In order to pull off this feat, researchers had to disable computer security features and even add a vulnerability to the DNA sequencing program.

Greg Hampikian, a professor of biology and criminal justice at Boise State said the more immediate vulnerabilities the researchers highlighted are concerning.

“If you could break into a crime lab you could alter data, but if you can break into the crime lab’s data, you have a much more efficient route. And if the data is altered, that’s what will be used to testify in court,” he said. “We’ve had accidents where tubes have been swapped. If you could maliciously alter or erase that’s obviously a big problem.”

Michael Marciano, a forensic molecular biologist at Syracuse University, said that while he believes the security practices in academic and medical research don’t present a threat at the moment, consumer DNA testing companies are a black box.

“With 23andMe and Ancestry you’re signing over your DNA to them, and how are they handling DNA security? There that data is linked to your name,” he said.

Because it’s unclear how that data is secured and used, he told Gizmodo, he even recommends that his students steer clear of consumer DNA tests.

“There’s nothing more sensitive than someone’s DNA,” he said.

This doesn’t mean that you should ring up your DNA testing service and ask that they destroy the files on your DNA. Instead, the researchers hope that highlighting these security issues before DNA data is more vulnerable to attack will prevent major hacks that spill our biological secrets.

“We don’t think people should change their behaviour today. DNA testing is important,” said Ney. “But as this technology matures and becomes more ubiquitous, it’s something the industry needs to think about. They’re working with very sensitive data.”